Movies are palaces of the imagination, showing us places we can’t go, either because they are closed to us, or too far away, or they never existed in the first place. Place is a star in its own right, and the places where movies are set are often the key to the psychology of the piece.

Sometimes the setting, and set, is found already built, seemingly just waiting for a camera to come and create an iconic image. And then there’s the house (or an entire city) that must be built from scratch in order to realize the director’s vision. These are sets that go way beyond the functional — they actually advance the mood, flavor, and drama of the piece.

We invite you to open the door to these houses with stories to tell.

“Rebecca” (1940)

Structure: Manderley, a fictional estate based on Menabilly, the historic English house restored by “Rebecca” author Daphne du Maurier. A scaled down version of Manderley/Menabilly was built on a soundstage. How important is the house? The opening line, spoken by Joan Fontaine, says it all, “Last night I dreamed I went to Manderley again.”

What It Stands For: A rotten, old of way of life must be destroyed so that new life can begin. Also, it’s not just the house that counts; it’s the housekeeper.

“Citizen Kane” (1941)

Structure: Xanadu, the world’s largest and most expensive estate, and home to newspaper mogul Charles Foster Kane (Orson Welles). Modeled in part on Oheka Castle on Long Island’s North Shore, but most comparable to Hearst Castle, the San Simeon, California, real-life Xanadu of Kane inspiration, publisher William Randolph Hearst.

What It Stands For: One man’s castle is another woman’s prison. Gilded cages are still cages. And there’s nothing enduringly fun about hearing echoes indoors.

“Jane Eyre” (1944)

Structure: Thornfield Hall — remote, moody, turreted and darkly romantic manor house of moody, darkly romantic squire, Mr. Rochester (Welles again), to whose ward Jane Eyre (Fontaine again!) is governess. Like the moors that surround it, Thornfield Hall was recreated from Charlotte Bronte’s classic novel on a Hollywood soundstage.

What It Stands For: Things are often not as they appear. Thornfield Hall is the house that gave us the first “madwoman in the attic.” (Get me outta here!)

“North By Northwest” (1959)

Structure: An immaculate homage to a Frank Lloyd Wright design, the house in the climactic scene of this classic mistaken identity yarn starring Cary Grant was built from the same materials used by Wright, in a studio on the MGM lot. The exterior shots were matte paintings. Director Alfred Hitchcock began as an art director, and thus, his sets are as masterful as his shots.

What It Stands For: American aesthetics and innovation at their mid-century height. Like “North By Northwest,” the house proves that style and substance can go hand-in-hand. Too bad the place is occupied by the bad guys.

“Contempt” (1963)

Structure: Casa Malaparte on the eastern side of the Isle of Capri is a red stone box built into a rock cliff that drops directly into the sea. A masterpiece of Italian modernism, Casa Malaparte was designed in 1937 by architect Adalberto Liberia.

What It Stands For: Even the most solid structures can be dangerous to inhabit, much like the marriage between a writer (Michel Piccoli), and his impossibly sexy wife (Brigitte Bardot). Their union crumbles, almost imperceptibly, on a troubled film project.

“Playtime” (1967)

Structure: A bewilderingly sleek fantasy Paris that became known as “Tativille,” was in reality an enormous, extravagantly costly set, built by a hundred craftsmen and running into the millions of francs. Tati’s lovable Monsieur Hulot loses his way in a city of glass and steel, cubes and slick facings.

What It Stands For: Our increasingly mechanised, modern life lacks the all-important human factor, which may at times look bumbling, but is in fact the most essential thing of all.

“Sleeper” (1973)

Structure: The Sculptured House, built in Colorado in 1963 by architect Charles Deaton, is now so identified with Woody Allen’s futuristic satire that it’s called “The Sleeper House.” The movie’s fictional device called the “Orgasmatron” was crafted from the sliding doors of the house’s cylindrical elevator.

What It Stands For: The future really may look as strange and be as socially corrupt as all those sociologists predicted. Also, the extreme design offers a striking backdrop for the prevailing silliness, which could actually take place at most any point in history.

“Howard’s End” (1992)

Structure: The ivy-covered English country house that, along with Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson, is the true star of “Howard’s End” (the title of E.M. Forster’s novel, and the name of the house that causes so much inter-familial angst) is realized by the real-life Peppard Cottage, in Oxfordshire. (No relation to actor George).

What It Stands For: Houses are forever; relationships are fleeting. But what a fuss and bother they sometimes cause before they fade away.

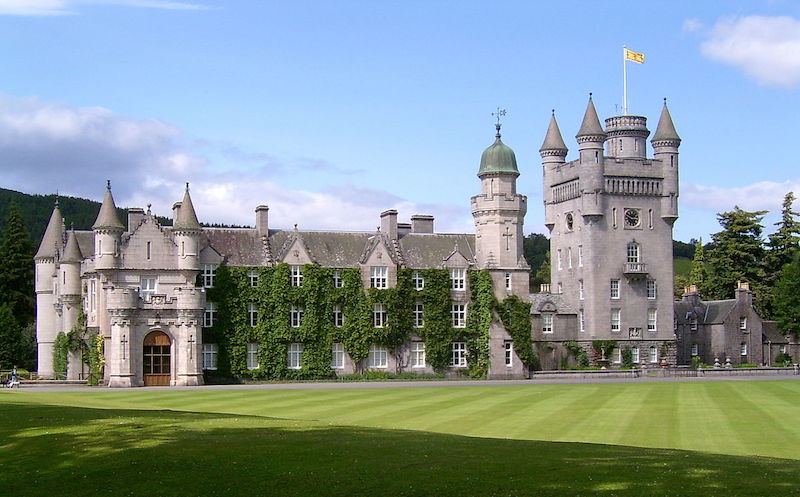

“The Queen” (2006)

Structures: English royal seats, Buckingham Palace, and Balmoral Castle.

What They Stand For: The distance between Queen Elizabeth II (Helen Mirren) and the British people who mourn the death of Princess Diana openly, while their monarch hides uncertainly inside her palaces. Sometimes (quite often in fact) it is better to rule in the streets than from behind the palace gates.