As film apes life, rain is inevitable in the cinema. Wet weather has driven plot, established a range of moods, and symbolically drenched countless spurned lovers and star-crossed suitors in untold romantic comedies. Thrillers and horror films use dark weather to cultivate a sense of dread – though if you’re going to get murdered, it would be much better to face your doom on a sandy beach, holding a Mai Tai.

Wait, weren’t we supposed to be happy it’s raining?

Let’s bring it back to the brighter side of spring – the cleansing feeling of the first spring downpour. April showers and their consequent May flowers, the last clumps of hard-packed snow melting off the sidewalk, Easter bunnies rutting amongst the chocolate eggs – you know, spring!

Each movie not only includes a pivotal rainy scene, but a rainy scene that advances the story in a hopeful way – all set to some of our favorite tunes. After this winter from hell, we all could use some upbeat music, dammit.

Top Hat

In the musical romance “Top Hat” (1935), it’s love at first dance for Jerry (Astaire) and the stunning Dale (Rogers), until Dale mistakenly believes Jerry is already married. Beyond the ineffable Astaire-Rogers chemistry, the real stars are a buttery Irving Berlin score and meticulously choreographed dance numbers. Featuring the song “Isn’t This A Lovely Day (To Be Caught In The Rain)”, Fred and Ginger come together on a rainy afternoon to re-kindle a romance. As always, Fred’s prospects improve on the dance floor. Were it only true for the rest of us. Stream “Top Hat” HERE!

Bambi

The animated classic “Bambi” (1942) marks one of Walt Disney’s crowning achievements. Bambi, a young deer born in the forest (where else – St. Jude’s of the Briar?), must face life’s savage realities when his mother becomes a delicious dinner for some lucky hunters. Before he becomes an orphan, however, there’s a scene where Bambi discovers the wonders of the natural world with the advent of spring. Set to the delicate strains of “Little April Shower,” it’s movie magic – unless the vicissitudes of life have turned your cynical heart to stone.

Singin’ In The Rain

But we mustn’t omit “Singin’ In The Rain” (1952), with the most iconic rainy scene in film. A tribute to (and satire of) the ‘20s, when Hollywood transitioned from silents to “talkies,” Gene Kelly plays Don Lockwood, an established star who falls for talented unknown Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds). Don schemes to advance her prospects by derailing the career of longtime co-star Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen), a shrill femme fatale who sounds like a “Little Rascals” impersonator. With a tight script, catchy period music, and athletic dancing routines, “Rain” is the funniest and amongst the best musicals ever made. Stream it HERE!

Breakfast At Tiffany’s

Cultural touchstone “Breakfast At Tiffany’s” (1961), from Truman Capote’s novella, would not be a classic without Audrey Hepburn’s bewitching presence. Audrey is Holly Golightly, a small-town Texas girl immersed in the glitz of New York’s social scene. George Peppard plays love interest Paul, a struggling writer. Will these two transplants get together? Late in the film, when Holly’s cat gets caught in the rain, we get our answer, set to the crescendo finish of Henry Mancini’s Oscar-winning “Moon River.” Bring your hankie. Stream it HERE!

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

From one touching ending, we finish with an unforgettable beginning, in Jacques Demy’s “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” (1964). “Cherbourg” begins with an ingenious overhead shot of rain falling on multi-hued umbrellas, while a soft rendition of Michel Legrand’s “I Will Wait for You” plays underneath. Ninteen-year-old Catherine Deneuve plays Genevieve, who works in her mother’s umbrella shop. She madly, truly loves Guy (Nino Castelnuovo), but then the poor guy gets drafted for military service, and the toll of separation gradually undermines their future. Demy’s visually sumptuous masterpiece is unique in that it’s all-sung, with no spoken dialogue. Thanks to a magical score by Legrand, it works.

“I admire Marlon’s talent, but I don’t envy the pain that created it.”

– Anthony Quinn

While fully acknowledging his prodigious talent, the prevailing sentiment of the critical community seems to be that Marlon Brando was a remote, tortured man who squandered his prodigious talent for easy money. Some pundits sound downright miffed, as if a good kick in Brando’s voluminous rear-end might have shocked him back to a full appreciation of just what he owed his public.

Brando’s filmography in fact provides sufficient proof that the actor’s own demons helped stall a career that in its hey-day (the mid-late fifties) seemed limitless in potential. Even though the Broadway stage had brought him sudden and early fame, as his career progressed Brando consciously resisted the traditional course of returning periodically to theatre to hone his craft with more demanding, highbrow works of classic and contemporary theatre.

Three personal qualities likely contributed to this decision: an inherent contrariness, the laziness that often accompanies success earned too quickly, and a corrosive contempt for his chosen profession, a path he chose only because it was the one thing he could do well.

Brando grew up the son of alcoholic parents — unappreciated, and often ignored. Desperate to gain attention from his pre-occupied mother, he learned to play-act and entertain from an early age. His early isolation bred in him both a vivid internal life and a seething resentment that would inform his acting persona and approach. In real life, his fundamental wariness and barely concealed self-loathing would make it difficult for him to trust and enjoy other people.

From the start, Brando’s public image reflected a basic truth about the man: he was complex, brooding, and angry, while at the same time child-like in his vulnerability. His ability to draw on the techniques of “The Method,” plumbing the depths of his unhappy, lonely childhood to create searing emotions on-screen, made him not just the embodiment of a new generation of actor, but a new kind of actor entirely, one perfectly in keeping with the darker realities of the post-war, atomic age.

Beyond the undeniable impact of “Method” proponent Stella Adler, to whom he credited with much of his success, Brando’s unique gift came from his uncanny ability to portray conflicting, suppressed emotions like no other actor before or since. Driving this was his core belief that the inner lives of human beings could not be drawn in black and white, only murky shades of gray. This meant that otherwise decent people, filled with hidden, often frightening contradictions, could inexplicably do horrible things.

Technique and motivation aside, the result was clear enough: no actor had ever filled a stage or a screen quite like Brando. Popular and critical adulation came at him like a tidal wave, and the actor privately dealt with the onslaught by dismissing the importance of his craft. He referred to acting as “an empty and useless profession,” and Hollywood as “a cultural boneyard.” His whole film career came to represent a paycheck he wasn’t principled enough to resist.

This sour outlook, coupled with a growing reputation as an erratic and unpredictable on-set personality, would result in a steadily diminishing quality of output in the sixties. Like Elizabeth Taylor, he became known for a time as a bloated has-been, a personification of the greed and self-indulgence of a now vanished Hollywood.

When Francis Ford Coppola approached him to audition for the part of Don Corleone in “The Godfather,” the actor had not worked in two years. Though Burt Lancaster was lobbying heavily for the role (ironically, the same actor who had launched Brando by turning down “Streetcar” on Broadway), he didn’t stand a chance once Marlon put that Kleenex in his cheeks.

In the wake of this iconic role and his second Oscar (which he famously refused), Brando milked his comeback by making one more notable film ( “Last Tango in Paris”), and then walking away from the industry, only returning when a pay day was too sweet to pass up. A telling quote from this period: “I’m not an actor and haven’t been for years. I’m a human being — hopefully a concerned and somewhat intelligent one — who occasionally acts.”

Though it’s difficult to deny the prevailing sense of waste in Brando’s career and life, he must be credited with acting on his idealism. He was a frequent supporter of the rights of disenfranchised groups, whether advocating for the plight of Native Americans, or lending his presence and support to the Civil Rights movement.

It is also true that he paid dearly for his shortcomings and mistakes, living to see his son Christian’s arrest for murder, and the eventual suicide of his daughter, Cheyenne. Who would wish this kind of pain on anyone?

Out of the spotlight and safe from prying eyes on his private Polynesian island, the star indulged in the only activity that provided real comfort: eating. Though always a prodigious gourmand, in later years the actor’s weight ballooned to 350 pounds (at 5’10”). Even on “Apocalypse Now,” shot when Brando was still in his fifties, director Francis Coppola had no alternative but to shoot the star in shadow, and when needed, utilize a stand-in. It was sad to think this obese figure had once played the lean, well-muscled Stanley Kowalski in a form-fitting tee-shirt.

Below are the Brando titles that remain in fine trim, demonstrating a striking, simple truth: no other actor could touch Marlon Brando at his best.

Welcome to the topsy-turvy world of the heist film, where most often the authorities are the dupes, and the crooks, daring heroes.

How do heist movies make this work? First, since usually the bad guys are in effect the protagonists, we get to know them as living, breathing characters. They gradually tap into our innate sympathy for the underdog, outcast, and rebel. The heist itself may come to represent the bigger challenges in our own lives, since the same elements determine success: intelligence, instinct, daring, planning, teamwork, and let’s not forget — luck.

These films generate considerable dramatic (or sometimes, comedic) tension, since high-stakes thieves are the ultimate gamblers: no amount of skill can fully eliminate the core risks involved, or the role of arbitrary fate.

Heist movies go back a long way and have been made all over the world, so it’s understandable if you’ve missed a few along the way. Here are some older heist films worth discovering.

First, one of the quintessential film noirs is also a heist film: John Huston’s “The Asphalt Jungle” (1950). A realistic, detailed chronicle of the planning, execution, and aftermath of a daring jewel robbery, “Jungle” is first and foremost a superb mood and character piece. Huston elicits compelling performances from the entire cast, including Sam Jaffe, a young Sterling Hayden, and in particular, Louis Calhern as the smooth but quietly desperate mastermind. (Also look for an early Marilyn Monroe appearance as Calhern’s mistress.)

Hayden would go on to work with a younger but equally talented director, Stanley Kubrick, on “The Killing” (1955), a documentary-like depiction of a race-track robbery. This early entry from the Kubrick canon delivers skillfully paced, edge-of-your-seat entertainment, featuring vivid characterizations. In particular, Elisha Cook, Jr. and Marie Windsor stand out as a wildly dysfunctional couple. Spare yet potent, “The Killing” lets you witness the budding of a cinematic genius.

I’ve always been a big fan of Jean Gabin, whom one perceptive critic described as “France’s answer to Spencer Tracy.” One of Gabin’s finest outings was a heist picture: Jacques Becker’s “Ne Touchez Pas Au Grisbi” (1954). The actor plays a high-class thief who’s ready to retire, and pulls off one last job to set himself up. He gets away with a stack of gold bars, but a rival gang finds out he did the job, and resolves to take his hard-won score away from him. (The film’s title is French slag for “don’t touch the loot”).

Two more excellent heist pictures were made by the very same man, the gifted Jules Dassin, who in the early ‘50s, under the cloud of the Hollywood Blacklist, left a successful directing career stateside to work in Europe. His first feature, made in France, was “Rififi” (1955), about a group of jewel thieves as distrustful of each other as the police- and not without reason. Viewed today, the movie retains its gritty realism: the justly famous heist sequence, done completely in silence, is riveting, and Jean Servais’s performance as the crime’s originator conveys a sad, twisted nobility. The conclusion of this small masterpiece will grip you and remain with you long after the closing credits.

Ten years later, Dassin released “Topkapi,” starring his wife, Greek actress Melina Mercouri, Maximilian Schell, and Peter Ustinov. This scenic, colorful movie (shot largely on location) constitutes lighter comic fare, with a motley crew of crooks attempting to steal a jewel-encrusted dagger from the heavily guarded Topkapi museum in Istanbul. Breezy and clever, the well-cast stars clearly enjoy themselves, except perhaps for sad-sack Ustinov. No matter: he won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance anyhow. (Incidentally, this film looks terrific on blu-ray).

Fast-forward to “The Great Train Robbery” (1979), an atmospheric thriller scripted and directed by best-selling author Michael Crichton. “Robbery” exudes a rich Victorian flavor, and features the surprisingly felicitous pairing of Sean Connery and Donald Sutherland as a team intent on stealing a large shipment of gold from a moving train. Based on a true story, “Robbery” is grand entertainment, with a fetching Lesley Ann Down completing the criminal trio, adding a welcome measure of feminine visual appeal.

In addition to “Topkapi,” my three heist comedy picks would have to be two Alec Guinness comedy classics made with Britain’s fabled Ealing Studios: “The Lavender Hill Mob” (1950) and “The Ladykillers” (1955), along with a third, lesser-known Italian chestnut, “Big Deal On Madonna Street” (1958).

“Mob” is the story of a seemingly timid but sly clerk who plots the perfect robbery of his own bank. This intricate crime’s planning and execution precipitate some of the more inspired comic sequences you’ll see on film. The ever-charming Stanley Holloway (who’d go on to play Alfie Doolittle in “My Fair Lady”) provides terrific support, and look fast in the first scene for a momentary glimpse of a future star, Audrey Hepburn.

“The Ladykillers” are actually a rag-tag bunch of lower-rung thieves and hoods, led by the smarmy Professor Marcus (Guinness). To provide convenient, suitable cover for their upcoming caper, they all board at the home of Mrs. Wilberforce (Katie Johnson), a frail, elderly widow, posing as musicians. Unfortunately for them, Mrs. Wilberforce is a good deal smarter and more alert than she appears, and the gang find themselves spending more time fending her off than planning the robbery. Guinness is priceless, both Peter Sellers and Herbert Lom (who’d reunite in the “Pink Panther” series), appear in early roles, and Miss Johnson nearly steals the picture as the diminutive but strong-willed landlady.

Finally, Mario Monicelli’s “Big Deal,” starring Marcello Mastroianni and Claudia Cardinale, unfolds in the broader, more expansive Italian style, with lots of yelling and frantic gesturing throughout the picture. This particular assemblage of thieves, who attempt to break into a pawn shop, may rank as the most bumbling in history. Delightfully, absurdly over-the-top, “Big Deal” is great fun for those who prefer their comedy with a hearty dose of Italian passion.

These heist movies work by tying us to the often unfortunate characters who populate them, investing us in their attempts to reach that same pot of gold, just out of reach. And we get that most satisfying of sensations — the vicarious thrill — knowing it’s them, not us, who are likely going to jail.

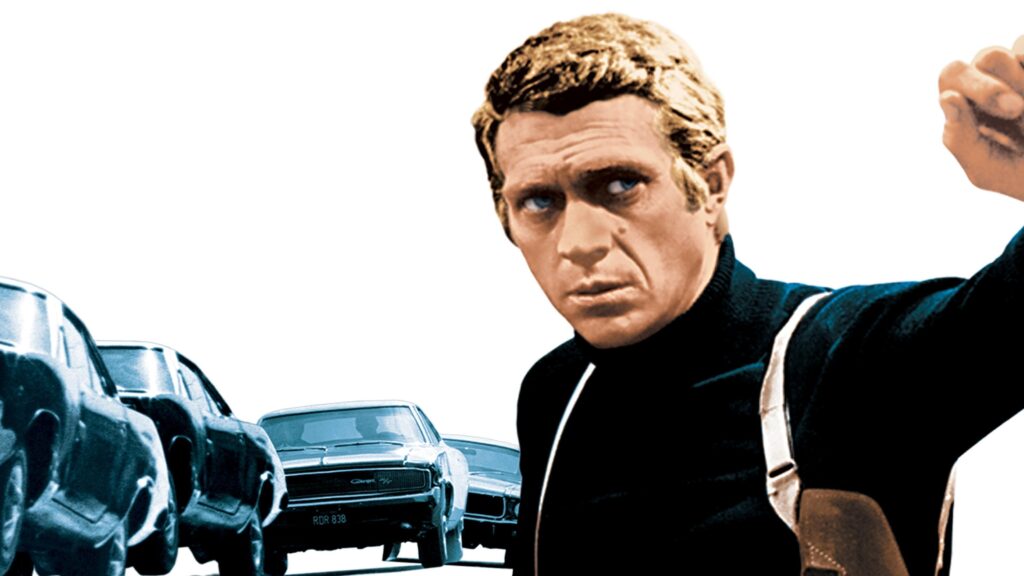

I love Steve McQueen, and I know I’m not alone.

For me, it’s impossible to separate the “King of Cool” from his passion for anything with wheels, excepting wheelchairs and tricycles. 1968’s “Bullitt” showed us what he could do in a souped-up Mustang. And five years prior, he displayed his motorcycle-riding prowess in the classic get-out-of-prison war film, “The Great Escape.”

RELATED: Watch This, Not That: “Bullitt” Not “Fast and Furious 6”

Now here’s an example of star power. Veteran director John Sturges added motorcycle sequences to the film as a concession to McQueen, who said he’d only play the part of Captain Virgil Hilts if he could display his skills on a bike. Sturges even let him tool around on his favorite make, a Triumph TR6 Trophy — which didn’t exist during World War II and had to be cosmetically modified.

In “Escape,” not only does McQueen perform nearly all the stunts for his own character, he actually dons an enemy uniform and appears as a Nazi motorcyclist during a pivotal chase scene. So, through the magic of editing, German Steve is hot on the trail of American Steve.

But wait-there’s more. To secure a bike upon his escape, Hilts (McQueen) strings a wire across a road, and a German soldier cruises right into the booby trap. Guess who plays the poor, hapless fellow that takes the spill? You guessed it- Steve again.

Kind of surreal, eh?

McQueen actually had to be held back from performing all the derring-do on wheels himself. This megastar was simply too valuable to be risking his neck for fun.

Example: for Hilts’s big jump over a barbed-wire fence, McQueen was replaced by friend and stunt-double Bud Ekins, since Steve had already tried the feat himself and crashed. Once burned…

Even off camera, it seems McQueen stayed in character. Racing through a nearby German town one day, he and several other crew members were caught in a speed trap and promptly arrested. The Chief of Police sternly advised the sheepish actor, “Herr McQueen, we have caught several of your comrades today, but you have won the prize [for the highest speeding].” McQueen was briefly locked up in jail for the offense. I hope he brought his baseball and glove.

Here’s a declarative statement that’s irrefutable: we need more female directors in Hollywood.

Just consider this: in the nearly hundred year history of the Oscars, female directors have received a paltry ten Best Director nominations– with the first, for Lina Wertmuller, occurring as recently as 1976.

Kathryn Bigelow finally achieved the first landmark win for women in 2010, snagging Best Director for “The Hurt Locker”, followed by wins for Chloe Zhao in 2020 (for “Nomadland”) and 2022 for Aussie veteran Jane Campion (“The Power of the Dog”).

It still feels like too little, too late, though it’s gratifying to see Coralie Farget on the nominees list this year for “The Substance”, even if her film is fatally overrated.

For any living fossils out there still wondering if female director can really cut it, I have a few titles for them (and you) to watch.

Cleo From 5 to 7 (1961), directed by Agnes Varda

This evocative French New Wave piece follows a pop singer around Paris as she awaits the results of tests that may confirm a serious illness. The time we spend with her makes us feel very much alive. Click here to stream it now!

Swept Away…By An Unusual Destiny In The Blue Sea Of August (1974), directed by Lina Wertmuller

Giancarlo Giannini is a cabin boy on a yacht owned by spoiled heiress Mariangela Melato. When they end up stuck together on a remote island, with no rescue in sight, the tables turn, and some intense, sexually charged conflict plays out. Click here to stream it now!

Harlan County, USA (1977), directed by Barbara Kopple

Brilliant documentary captures one of the seminal confrontations in labor history, as Kentucky coal miners fight for improved working conditions from their employer, The Eastover Mining Company. Click here to stream it now!

Fast Times At Ridgemont High (1982), directed by Amy Heckerling

Buoyant teen comedy/romance centers on various student shenanigans at a California high school. A young Sean Penn steals the picture as an unapologetic stoner. Click here to stream it now!

Big (1988) directed by Penny Marshall

At a carnival, a young boy makes a wish to be all grown up, and the next morning, he wakes up as Tom Hanks. You may think the premise sounds silly, but the film really works. It’s both funny and touching. Click here to stream it now!

Salaam Bombay (1988), directed by Mira Nair

A young Indian boy gets kicked out of his home, and must somehow survive on the streets of Bombay. His heart-rending odyssey features some colorful characters he befriends, but, like him, they are stuck in a circle of poverty, and cannot alter the uncertain future he faces. Click here to stream it now!

Orlando (1992), directed by Sally Potter

Based on Virginia Woolf’s book, Tilda Swinton plays the title character, who is given immortality and goes on to experience a series of exciting lives while alternating sexes. Only an actor as talented as Swinton could pull off this gender-bending role so convincingly. Click here to stream it now!

The Piano (1993), directed by Jane Campion

Holly Hunter plays a mute widow and mail order bride who travels with her daughter to remote New Zealand to marry a farmer (Sam Neill). Once there, she starts giving piano lessons to Harvey Keitel, who lives nearby; soon the teacher-pupil relationship erupts into a passionate affair. Click here to stream it now!

Boys Don’t Cry (1999), directed by Kimberly Peirce

Based on a true story, Hilary Swank plays Nebraskan Brandon Teena, who was born a woman but began to live as a man. When some of the locals discover her secret, things get really ugly. Click here to stream it now!

Lost In Translation (2003), directed by Sofia Coppola

Bill Murray is a jaded actor who travels to Tokyo to shoot a whiskey ad. He happens to meet twenty-something Scarlett Johansson, who’s also emotionally adrift, and these two lost souls develop an unlikely bond. Click here to stream it now!

Water (2006) directed by Deepa Mehta

In accordance with tradition, a child bride turned widow is sent to live in an ashram from which she’s unlikely to emerge. There she meets two older women who become her friends and inject an element of warmth and joy into her otherwise ascetic life. Click here to stream it now!

Winter’s Bone (2010), directed by Debra Granik

Jennifer Lawrence plays an adolescent girl forced to care for her family, living in poverty in the Ozarks after their drug dealing father leaves. When the authorities inform her their house will be repossessed if her dad misses his next court date, she must go out and find him at any cost. Click here to stream it now!

Lady Bird (2010), directed by Debra Granik

Saorise Ronan plays a quirky, rebellious teen stuck in a Catholic school with big plans for the future. Laurie Metcalf is her frustrated mother, with issues of her own, who tries to bring her back down to earth. Tangy coming-of-age tale drew Oscar nods for Ronan, Metcalf, and Gerwig. Click here to stream it now!

Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020), directed by Eliza Hittman

Shot in a documentary style that suits the story, this film portrays, up close and personal, the unnerving experience of Autumn (Sidney Flanigan), a seventeen-year-old Pennsylvania native forced to sneak up to New York City for an abortion with her loyal cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder). Click here to stream it now!

As I explore in a separate piece, over the course of nearly a century the movie god we know as “Oscar” has often gotten it wrong. Examples abound across the decades, giving us movie buffs plentiful material for spirited debate.

This year, there were no clear favorites going in for Best Picture, but I had my own pick: Sean Baker’s “Anora”. So imagine my delight when it prevailed last night, winning five major awards, including Best Picture, Director, and Actress.

It’s a moment for rejoicing, as this time the Academy (and its voters) got it just right. To celebrate, here’s the piece I wrote about this special film a couple of months’ back.

If you have yet to see “Anora”, you’re overdue!

As each year draws to a close, I always look for that one unexpected, under-the radar film that has everyone buzzing, more from word-of-mouth than heavy publicity.

The one movie that seems to come out of nowhere. The one that surprises me most, the one I watch again, the one that renews my faith in movies.

Most often it’s not a big-budget Hollywood release. For me last year, that single film was “Anatomy of a Fall”, starring German actress Sandra Huller, which eventually won the Oscar for Original Screenplay.

This year, without question it’s Sean Baker’s “Anora”, the first American movie to win the prestigious Palme d’Or at Cannes since Terence Malick’s “The Tree of Life” (2011).

Streaming now, “Anora” imbues a seemingly tawdry tale with tremendous heart and humanity. Oh, and it’s extremely funny too.

The title character (Mikey Madison) is a Brooklyn-based exotic dancer who does escort work on the side. One night at the Manhattan club where she works, she meets Vanya (Mark Eydelshteyn), a Russian youth who claims to be 21 but looks younger.

Regardless of age, Vanya has money to burn and soon hires “Ani”(the nickname she prefers) as his exclusive girlfriend for a week of excessive partying and frantic sex. A mad spark of romance results in a more binding arrangement.

But how will Vanya’s Russian oligarch father and ice-cold, ruthless mother react when they learn their son has tied the knot with an American call girl? Finding out is one wild, exhilarating ride, by turns hilariously profane and deeply moving.

Director Sean Baker (“The Florida Project”) and team really hit the bull’s-eye here, and Madison’s fearless yet nuanced turn as Ani is star-making.

Have I convinced you yet? “Anora” is indeed my favorite movie of 2024, the one that makes me believe in movies all over again. Stream it soon!

We all make mistakes.

From leisure suits in the ‘70s, to “hyper color” clothing in the ‘80s, to rat tail haircuts anytime, we Americans are notorious for making choices that seemed like good ideas at the time. Yet, we tend to demand more of our finest institutions. In particular, we expect our most prestigious award-givers to choose the right winners. Is that too much to ask?

When Oscar Gets It Wrong

So how often does the Academy get it WRONG! Let’s take a look back at a few instances that left me shaking my head…

Take the Academy Awards (please!), and specifically, their prestigious award for Best Picture. In 2009, the Academy made the fateful decision to expand the nominee pool to ten, at a time when fewer great, Oscar-worthy films are actually being made. (Don’t get me started.) In my view, rather than broaden interest in the Awards, that dubious move diluted the impact of their top prize. Oh, well.

That was a big mistake, but hardly the first. To illustrate, let’s go back through history and point out the most obvious missteps in the history of the Oscars. Focusing on past recipients of the three major awards (Best Picture, Actor and Actress), we’ll identify the times when Oscar really fell down on the job.

To the list!

THE LIST

1936 – Amongst other poor decisions, “My Man Godfrey,” alpha dog of the screwball comedy wolfpack, wasn’t nominated for Best Picture though it did get nods in all acting categories.( “The Great Ziegfeld”, another William Powell picture, prevailed). For her work in “Godfrey,” Carole Lombard (who lost) deserved to have Luise Rainer (who won) kissing her feet as she walked up to give her acceptance speech. Worse, Chaplin’s “Modern Times” received no nominations.

1944 – No doubt about it: Billy Wilder’s gritty “Double Indemnity” should have triumphed over the sentimental “Going My Way” for Best Picture. Furthermore, “Double” starlet Barbara Stanwyck should’ve won the Oscar for Best Actress, and her co-stars, Fred MacMurray and Edward G. Robinson, should’ve at least had nominations, if not wins.

1952 – Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Greatest Show On Earth” was a lousy choice for Best Picture. Watch it today and see if you don’t want to strangle Betty Hutton and Cornel Wilde. A better choice would’ve been the iconic “High Noon,” but it angered too many judges who wanted to bury “Noon” for drawing parallels to the rampant blacklisting of the time.

1956 – The bloated “Around The World In Eighty Days” shouldn’t have won Best Picture over “Giant.” We also think James Dean deserved to win a posthumous Oscar over Yul Brynner’s (albeit great) work in “The King and I.” Finally, John Ford’s “The Searchers” should have been nominated for Best Picture.

1960 – Best Picture winner “The Apartment” should have swept the three big categories; both Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine were wholly deserving of Oscars that year. Instead, statuettes went to Burt Lancaster who played it broad (even for him) in “Elmer Gantry,” and Elizabeth Taylor yawned her way to a win in the forgettable “Butterfield 8.”

1964 – Not that I dislike musicals, but “Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” should have nuked “My Fair Lady” for Best Picture. Also, for his brilliant work essaying three roles in that film, Peter Sellers should have received Best Actor over “Sexy Rexy” Harrison. Sweet revenge: Julie Andrews, who’d been passed over for “Lady” after starring in it on Broadway, won the Oscar that year for a different movie: “Mary Poppins.” Studio chief Jack Warner had egg on his face over that one.

1973 – We absolutely love “The Sting,” but as the more memorable and groundbreaking film, “The Exorcist” should’ve “possessed” the Best Picture statue. For her gut-wrenching work, Ellen Burstyn should have snagged Best Actress over Glenda Jackson, who slummed it, albeit appealingly, in “A Touch Of Class.”

1976 – In our world, “Taxi Driver” out-boxed “Rocky” for Best Picture, and DeNiro would get the Oscar over tthe late Peter Finch in “Network,” for Best Actor. Also, Beatrice Straight got Best Supporting Actress for a performance with only five minutes’ screen time; it’s clear Piper Laurie should have slashed her way to that Oscar playing Sissy Spacek’s demented mother in “Carrie”.

1989 – If we’d run things, “My Left Foot” would have wheeled its way to Best Picture over the pedestrian “Driving Miss Daisy,” or failing that, we’d even knock in “Field Of Dreams.” Not much more to complain about here, but that error was a doozy!

1994 – This is a year that deserves an article all to itself, or maybe even a book. Why? The idea that sappy sweet Forrest Gump, like its central character, should have stumbled aimlessly into Best Picture. That it won over the game-changing “Pulp Fiction” is a tragedy better left for a Shakespearean play. Likewise for Actor, Travolta should have trumped “Box Of Chocolates” Hanks.

1996 – “Fargo” should’ve thrown “The English Patient” in the proverbial wood chipper for Best Picture. Granted, two very different movies, but come on! At least Frances McDormand won her first of three Oscars for this.

1997 – Top of the world? More like bottom of the barrel. Either “As Good As It Gets” or “L.A Confidential” was a (sea-)worthy pick for Best Picture before the bloated “Titanic”, which wowed in culminating effects sequences, but prior to that, unfolded a pretty soggy (and awfully familiar) romance. I know many disagree.

1998 – Foreign films ruled this year. For Best Picture, “Life Is Beautiful” ought to have won over “Shakespeare In Love.” Also, if we’ve got the time machine working, let’s give Fernanda Montenegro from “Central Station” the Best Actress award.

2000 – Come on, savvy film folk: Steven Soderbergh’s “Traffic” was the best film of the year, not that sword-and-sandals retread,, “Gladiator.” Furthermore, Ed Harris warranted Best Actor for his incredible work in “Pollock,” and Actress should’ve gone to Joan Allen in “The Contender” over Julia Roberts’s somewhat cheesy “Erin Brockovich.”

2002 – We’d have picked “The Hours” over “Chicago” for Best Picture (but it wasn’t a stellar year anyhow). And Gere ain’t no Fred Astaire.

2004 – For Best Picture, we thought “Hotel Rwanda” packed more of a punch than “Million Dollar Baby“, and we were mighty sore that the superb “Vera Drake” wasn’t even nominated. Its star, Imelda Staunton, also deserved Best Actress.

2005 – “Crash” wins Best Picture? An intriguing, if somewhat muddled first feature from Paul Haggis, it hardly deserved it, though it was a down year. Of the nominees, “Capote” would have been the obvious choice. You was robbed, Truman!

2006 – I know devotees will differ, but with respect to Mr. Scorsese’s victorious “The Departed”, the original Chinese film on which it was based (2002’s “Infernal Affairs“) was leaner and meaner, with no hammy Jack Nicholson performance. Either “Letters From Iwo Jima” or “Little Miss Sunshine” should have prevailed.

2012 – No way “Argo” should have won out over “Lincoln.” Though the Academy made some amends by giving Daniel Day-Lewis another Oscar for his astonishing portrayal in the title role, which rivals Henny Fonda’s superb portrayal in “Young Mr. Lincoln” (1939).

2018 – Now I enjoyed Best Picture winner “The Green Book”, and as good, solid storytelling would leaf though it again. That said, Alfonso Cuaron’s “Roma” was an instant classic that should have taken Oscars heart that year.

2025 – As to the present, “Anora” was the big winner in 2025, taking home five major Oscars, including Best Picture, Director (for Sean Baker) and Actress (for Mikey Madison). Since this was my own pick for last year’s best movie, I’m delighted to note that sometimes, Oscar gets it right too.

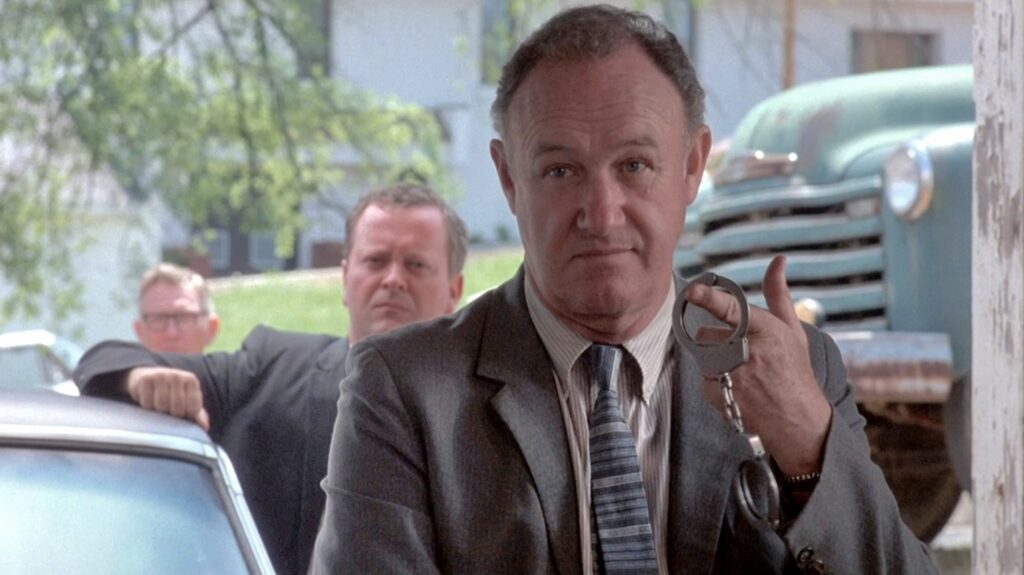

The story of Gene Hackman, one of the finest screen actors of his generation, is one of raw will and talent, overcoming a host of limitations that would have defeated most people.

Born in 1930, Gene was the child of a broken home who lied to get into the Marines at 16. Later, he would study at the University of Illinois on the G.I. Bill, while maintaining a series of menial jobs, from doorman to furniture mover. At thirty, he still had no idea what his true calling was.

Then one day he flashed back to seeing Brando nearly a decade before in “A Streetcar Named Desire.” Compared to the traditional glamorous Hollywood star, there was something powerfully authentic about the way Brando looked and performed. Hackman remembered thinking that maybe he could do that. Newly inspired, he promptly enrolled in The Pasadena Playhouse.

If Hackman was seeking some validation of his abilities there, he did not find it. Receiving rock-bottom ratings for his efforts, he decided to move to the theatrical mecca of New York, where soon enough he’d be sharing an apartment with fellow Playhouse alum Dustin Hoffman. These were the lean times.

After doing off-Broadway work and summer stock, in 1964 Gene was chosen for a Broadway part where he received good notices. This led to a small role in the Warren Beatty film, “Lilith.” Beatty, several years Gene’s junior but already a big star, was sufficiently impressed by his abilities to later cast him as his brother Buck in the breakout hit “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967).

Suddenly, Gene was in demand. Against all odds, he’d become a bankable featured player, which was really all he’d wanted. Stardom did not seem desirable, much less attainable. But his output was simply too good to ignore: after receiving a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nod for “Bonnie,” he got another three years later for the underrated drama, “I Never Sang For My Father” (1970).

The French Connection

A young director named William Friedkin knocked on Gene’s door, seeking a lead actor for a cop film based on a true story…

“The French Connection” (1970), but Gene was not the first choice; a host of other actors, including Robert Mitchum, Lee Marvin, Steve McQueen, and Peter Boyle, had turned it down. Incredibly, journalist Jimmy Breslin had been tapped for the part, but Friedkin was reconsidering that choice after several weeks of rehearsals.

Gene, of course, devoured the role, netting that year’s Academy Award for Best Actor. Like it or not, he was now a star, and a star he would remain. Over the next thirty-plus years, Gene became one of the most admired and prolific screen actors in the business. He was Oscar nominated again for “Mississippi Burning” (1988), and won the Supporting Actor statuette for Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven” (1992).

In 2004, Gene Hackman retired from the screen at the age of 74. It was a characteristically quiet and graceful exit. Of course, we will miss him dearly, but his best work sustains us.

Here’s to you, Popeye.

More: How Walter Matthau Got His Start

Enjoyed this article? Tired of endlessly scrolling?

Join Now and find better movies, faster.

Commemorating the Centenary

Consummate actor Jack Lemmon had a habit of saying to himself before every take: “It’s magic time.” This may strike some people as mildly eccentric, but I would remind them that magic is precisely what he went on to create.

Lemmon was one of those rare stars that people actually felt was one of them. The fact that he was Andover and Harvard educated never entered into the debate. Beyond Lemmon’s infectious energy and enormous talent, viewers responded viscerally to his sheer humanity. Jack was never afraid to play a real human being, warts and all.

His career turning point came with the classic “Mister Roberts” (1955). Grouped with veteran stars Henry Fonda, James Cagney, and William Powell, Lemmon imbued the supporting role of Ensign Pulver with such humor and zest that he nabbed that year’s Best Supporting Actor Oscar. Though he wouldn’t win the Best Actor Statuette until 1974, he’d be nominated for it three times up to that point, and three times after.

For those wanting to mark his centennial by revisiting his finest work, here’s my own list of top Lemmon outings:

Some Like It Hot (1959)

Peerless Billy Wilder comedy has Jack and Tony Curtis cross-dressing and joining a traveling all-female band to elude the mobsters on their tail. Marilyn Monroe plays a chanteuse named Sugar Kane!

The Apartment (1960)

Jack is an insurance man whose career advances once he starts lending out his apartment to his bosses for private trysts. Shirley MacLaine is the elevator girl he loves.

The Days Of Wine and Roses (1962)

Lemmon plays a salesman whose heavy drinking soon turns into full-blown alcoholism. He marries innocent Lee Remick, and turns her into a lush too. Is redemption possible?

The Odd Couple (1968)

In this inspired Neil Simon outing, Jack and frequent co-star Walter Matthau play two divorced men who become unlikely roommates. The problem: they are polar opposites. By comparison with this arrangement, marriage was easy!

The China Syndrome (1979)

In this brainy thriller, Lemmon plays a supervisor at a nuclear power plant who decides to blow the whistle on his employer’s shoddy safety practices. Jane Fonda and Michael Douglas are journalists looking to uncover the story.

Missing (1983)

In this fact-based story, Jack is a father who travels to South America in search of his estranged son, who has disappeared. As he teams with daughter-in-law Sissy Spacek to unravel the mystery, he learns some unpleasant truths.

Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Lemmon is heartbreaking as a once-hot salesman who’s lost his touch. Beset by financial problems and confronting a humiliating future, he becomes increasingly desperate. The actor delivers a stunning portrait of human disintegration.

More: How Marilyn Monroe Almost Derailed “Some Like It Hot”

Looking back at his career, it is tempting to focus solely on those piercing blue eyes. There wasn’t a pair to match them in a business where eyes are the primary means of expression, and Newman’s continue to shine, years after his passing, with an illuminating brilliance.

But of course, Newman’s iconic power lies in the fact that he never rested on his looks, instead using the intelligence behind those eyes to create a catalogue of classic film roles, a successful business empire, and a lasting philanthropic legacy. In fact, it could be said that he successfully broke out of the prison of his handsome face, to reveal the complex, yet fundamentally decent, person within.

Born in an upscale neighborhood of Shaker Heights, Ohio, Newman found his gift for acting in childhood and pursued it right through his service as a WWII airman. Ironically, when it was discovered that those startlingly blue eyes were in fact color blind, Newman was benched for a time from combat, eventually becoming a radio operator.

Five decades later, Newman would become so well known for his work outside of acting, primarily via his “Newman’s Own” line of foods, that some needed reminding that his path to fame began on small stages studying acting, first at the Yale School of Drama, and then with the father of method acting, Lee Strasberg, at the Actors Studio in New York.

From those stages, where his classmates included Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Karl Malden, emerged an actor with his own brand of integrity, whose characters reflected his rebellious spirit, but also his sense of justice and fairness. Strasberg once commented that Newman could have been as great an actor as Brando if he hadn’t been so handsome.

But would his sense of humor have been as delightful and unexpected? In much the same way that George Clooney uses mischievous humor as a foil for his looks, Newman used his to cut against the grain of a masculine beauty so strong that it could have become a barrier between him and the audience. He would never allow that to happen.

Throughout his long career, Newman stretched his range, but always returned to the wry, funny, relaxed persona that defined his public persona. I’d suggest his unique brand of charm was best showcased in two particular films: “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969), and “The Sting,” (1973). The humor shows up in his eyes, and while blue eyes are often called “steely,” Newman’s were perennially friendly, with a glint of the bad boy sparkling in the corner.

He knew exactly what he was doing, always, and could not help but bring a bit of the imp to any role that wasn’t intentionally downbeat. For example, when the first cut of “Butch Cassidy” was completed, it was deemed “too funny” and had to be re-cut. Most filmmakers would relish having that as a problem!

Naturally, Newman knew just how potent his eyes were, saying once that he could envision his epitaph: “Here lies Paul Newman, who died a failure because his eyes turned brown.” That is the ultimate joke. The eyes are the window to the soul, and while this pair may have been more clear, more blue, more bright than any other on film, ultimately it’s the way they speak to us, and the understanding and sympathy they convey, that make them (and him) so beautiful.