You’ll hear a lot about patriotism this weekend. I already got an email saying it was my patriotic duty to get in on a great car deal. Even beyond the stupendous sales out there, there are the barbecues, parades, fireworks, and at some point, maybe even a warbling of the National Anthem. (Get on your feet, boy. Stand up straight, and put that hand where it belongs- across your chest!)

But what exactly is behind all the familiar rituals and noise? What's it all about?

Well, let's see. Today we're celebrating the place we call home, the most powerful nation on Earth, a bastion of freedom and opportunity — the single destination where countless struggling people around the world still want to end up. "The American Dream" lives on.

Yet since its founding, our country has been only as noble as the citizens that have led and occupied it. So all the strengths and accomplishments we highlight today are offset by darker deeds, fueled by hubris, greed, ignorance and fear.

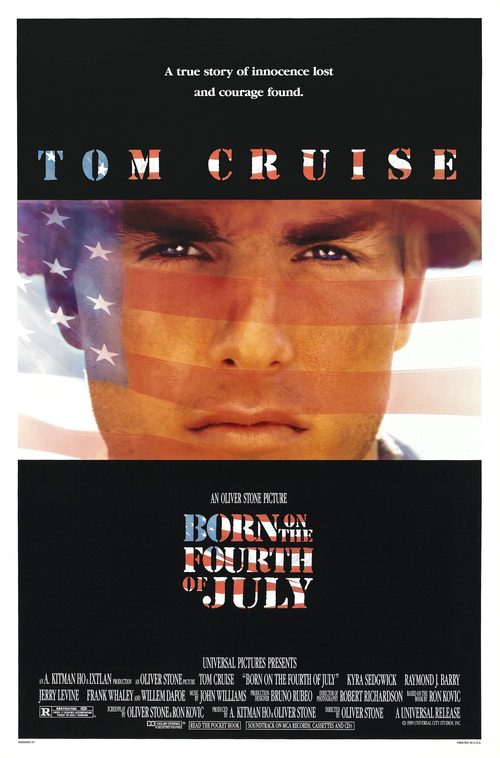

To illustrate my point, let’s compare two films that use Independence Day as their rallying cry: “Yankee Doodle Dandy” (1942), about legendary producer/songwriter George M. Cohan, and “Born on the Fourth of July” (1989), which profiles soldier-turned-activist Ron Kovic. Though they portray the “land that I love” from vastly different perspectives, reflecting a nation dramatically transformed over thirty years, the two movies actually have more in common than you’d expect.

First, both films are based on fact. At the heart of both is the theme of patriotism — how it can be used to help us prevail in a just cause, and twisted to cause needless death and destruction in an unjust one. Both titles were hits, each scoring 8 Oscar nods, including Best Picture, Actor, and Director. Of these major nominations, each film won one- Cagney scored for “Yankee Doodle”, while director Oliver Stone won for “July”.

Now here's a more bizarre coincidence: both films’ stars, and the characters they portray, were all born either on, or close to, this holiday . Kovic and Cruise arrived on the Fourth, Cohan the day before, and Cagney exactly two weeks after Cohan. (I ask you, what are the chances?)

Beyond these surprising similarities, one movie glorifies the finest aspects of our national character, while the other exposes its deeply flawed, if not downright nefarious, flip-side.

“Yankee Doodle” spins the tale of showman Cohan, whose distinctly American music fueled pride of country in the early twentieth century (“You’re A Grand Old Flag” “The Yankee Doodle Boy”), then rallied a nation during World War I (“Over There”). Cohan’s songs and plays captured a time when America was still young, booming and understandably optimistic, not yet the beleaguered “policeman to the world”. It was a simpler time when vaudeville and live theatre still held sway.

We watch as Cohan, born with greasepaint in his veins, tours the vaudeville circuit with his family as the “Four Cohans”, and quickly becomes the leader of the act, closing every performance with “My father thanks you, my mother thanks you, my sister thanks you, and I thank you.”) Soon, George graduates to songwriting and production, becoming the biggest theatrical impresario of his day.

Cagney, most always saddled with gangster parts up to that point, gets a chance to show off his early training as a song-and-dance man, and boy, does it pay off. How incredibly satisfying for Jimmy to finally win his Oscar for the type of role he’d always wanted to play. His supporting cast was every bit as good, including the ever-fabulous Walter Huston (director John’s dad) and ingenue Joan Leslie. In its time, the film constituted powerful propaganda for the U.S. as it entered its second World War in twenty-five years. Over seven decades later, “Yankee Doodle” remains a touching, rousing valentine to a growing country blessed with seemingly endless potential.

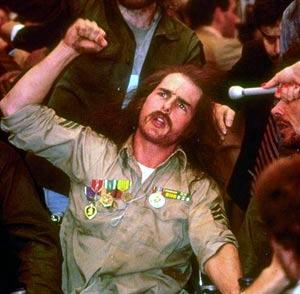

Conversely, “July” tells the story of Ron Kovic, an idealistic young man from Massapequa, New York. His story begins with a placid middle-class upbringing in the conformist, complacent fifties. Along with his peers, he’s taught that Communism is the ultimate threat, so, once of age, he wants to do his part in Vietnam. Ron starts his tour, and first mistakenly kills one of his own men in a firefight. Then an enemy bullet finds him, leaving him paralyzed. And for what? Back home, Ron’s in turmoil, as his ideals of God and Country recede against the struggles to advance civil rights and end the war. From his wheelchair, he becomes a leading anti-war activist.

The leading man handsome, clean-scrubbed Cruise may have seemed an unlikely choice for Kovic, but he was then the biggest star in Hollywood, and wisely wanted a grittier, more challenging part to stretch himself and discourage typecasting. Who was Oliver Stone to argue? As it turns out, there was no need: the film was a triumph.

Now- doesn’t the prospect of watching these two great movies make you feel like saluting the flag? What the heck- maybe I’ll go out and buy that car!

Are there other films that speak to you about what America really means? Let me know on Facebook.