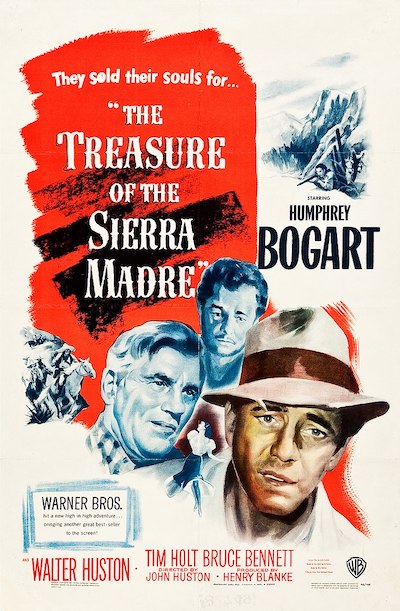

Over the course of a distinguished film career as writer, director, and actor, 1948’s “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” marked a memorable juncture for John Huston.

This was a film he’d wanted to make for over a decade, ever since reading B. Craven’s book about three down on their luck Americans south of the border who team up to prospect for gold. When they succeed, greed and distrust threaten to undo all they’ve achieved.

Huston had fallen under the spell of Mexico when he’d traveled there as a young man pondering his future. When Craven’s book came out in the States in 1935, he had devoured it and vowed one day to put it on the screen.

Back then Huston thought his actor father Walter would be perfect to play the central character, Fred C. Dobbs. However, still in his late twenties, John was in no position yet to suggest a film, much less cast one.

However, a short five years later, he was. He had since proven himself a gifted screenwriter at Warners with such pictures as “Jezebel” (1938) and “Sergeant York” (1941). He decided to lobby studio head Jack Warner for a shot at directing.

Warner responded that if his next screenplay produced a hit, he’d get his chance. That script turned out to be “High Sierra,” the film that started the process of transforming supporting player Humphrey Bogart into a full-fledged star.

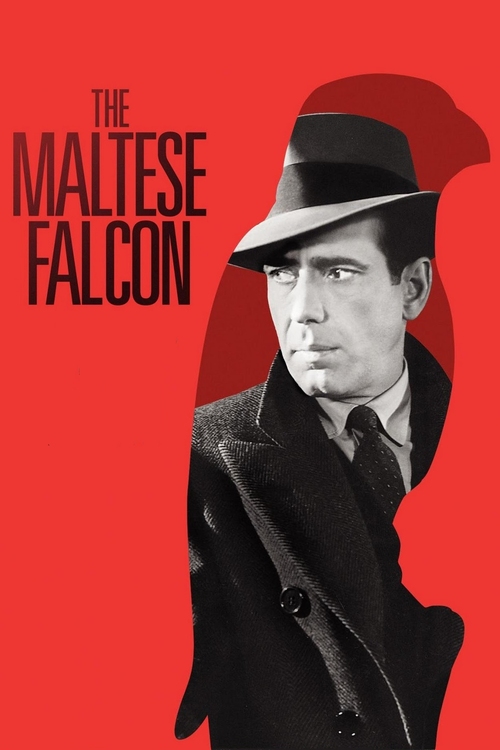

Huston’s first directorial effort, “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), would feature Bogart, and complete the one-two punch that would virtually guarantee his name would henceforth appear above the title. The forty year old actor was properly grateful, and also sensed the younger man’s brilliance. He also liked him personally, and they became drinking buddies off the set.

The two men would collaborate once more, on 1942’s “Across the Pacific,” before the war took Huston overseas. All the while, “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” was on his mind.

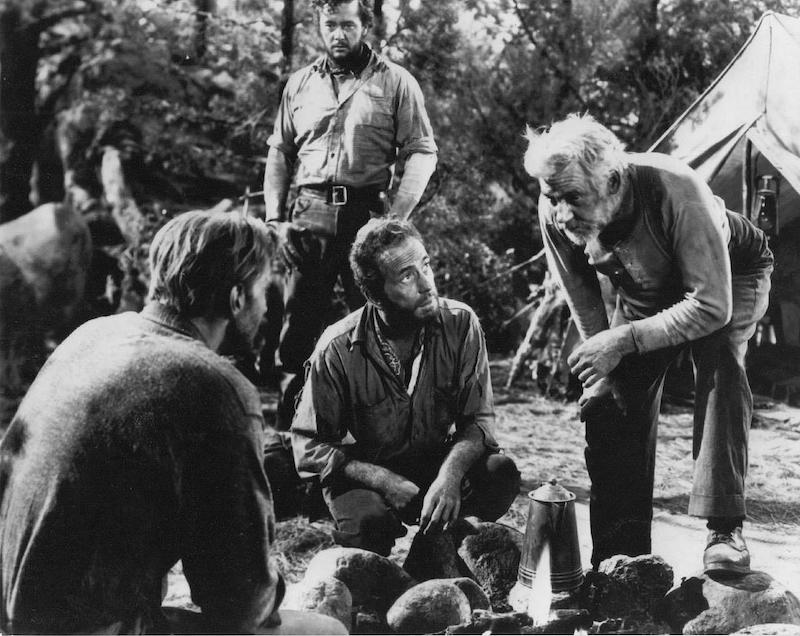

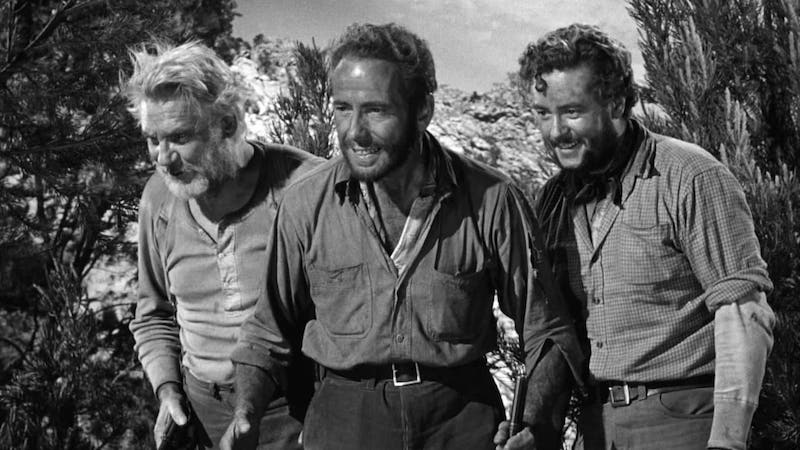

The war over, Huston finally saw his chance for “Treasure.” Bogart heard about it, and predictably coveted the starring role of Fred C. Dobbs. Huston quickly realized there was still a juicy part available for his father, that of the old grizzled prospector Howard, who is the voice of reason and experience in the story.

Walter Huston would take some convincing: he was used to being a star, and this was a supporting role. Walter would have to grow a scruffy beard, and John even wanted him to do the whole movie without his false teeth! Still, he knew this was a good role in a potentially great picture and also wanted to work with his son, so he eventually accepted.

For the third and youngest pf the prospectors, the director cast Tim Holt, best known for Orson Welles’s “The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942). Other key supporting roles in this all-male cast were played by Bruce Bennett and Barton MacLane. A young Robert Blake was cast as the Mexican boy who sells Dobbs a lottery ticket.

Jack Warner was observing developments with growing concern. On the one hand, he knew Huston was on to something that could turn out exceptionally well. To help his director achieve the realism he sought, he had even authorized having the film shot on location in Mexico. This had never been done before.

On the other hand, he was concerned about the film’s commercial prospects. “Treasure” was a dark story, devoid of glamour and leading ladies. His star, so often the tough but noble hero, would play an irredeemable lowlife here. Would his fans come out for it?

Bogart himself was grateful for a change of pace. Leaving a nightclub one night, he called out to a journalist friend: “Wait till you see me in my next picture. I play the biggest s**t you ever saw!”

Warner regretted his decision to let the company shoot in Mexico almost as soon as they arrived. Supposedly some palms had not been properly greased locally and officials ordered the production shut down just as shooting commenced, causing schedule delays and cost overruns.

Once production finally resumed, Huston’s fabled perfectionism kicked in, with lots of retakes and film exposed. The budget would eventually balloon to $3 million, by far the most expensive production in Warner’s history. At one point, a livid Jack Warner was heard to remark: “Yeah, they’re looking for gold all right. Mine!”

Eventually, he ordered the cast and crew back to Hollywood to finish the picture.

Warner’s concerns were soon borne out. He had a great film on his hands that would not make money — at least not initially. When the film was released, critics praised it, but its hefty budget almost ensured it would not break even at the box office. Even so, Warner would later admit it was among the best films his studio had ever made.

Warner’s concerns were soon borne out. He had a great film on his hands that would not make money — at least not initially. When the film was released, critics praised it, but its hefty budget almost ensured it would not break even at the box office. Even so, Warner would later admit it was among the best films his studio had ever made.

And — as with most all enduring classics, it would make a lot more money over time.

At the Oscars that year, it was a magical night for the Huston family, as father Walter won for Best Supporting Actor and son John took home two statuettes, for directing and screenwriting. The film was also nominated for Best Picture but lost out to Olivier’s “Hamlet.”

This marked the first time in Oscar history that a father and son won awards for the same film, a record which would hold until father Carmine and son Francis Ford Coppola both scored for their work on “The Godfather, Part 2” (1974).

Walter Huston’s acceptance speech was a highlight of the evening. Looking out at the star-studded crowd, he appeared every bit the proud father as he said: "Many, many years ago, I brought up a boy and I said to him, 'Son, if you ever become a writer, try to write a good part for your old man sometime'. Well, by cracky, that's what he did!"

No argument there, Mr. Huston.