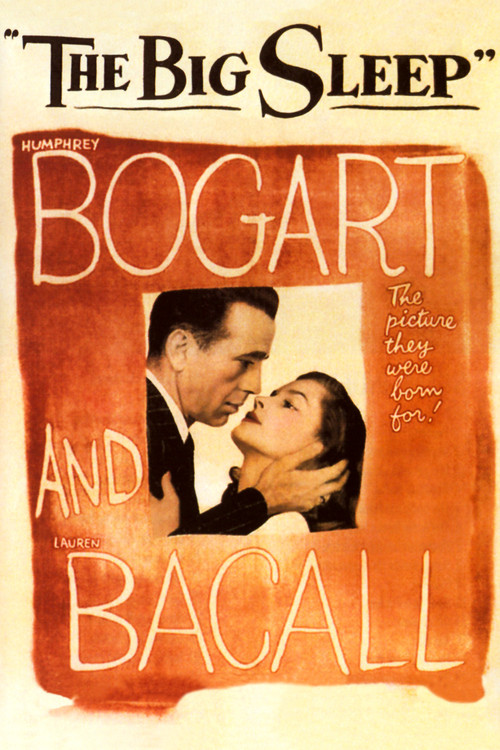

Film scholars may differ on the top Bogart-Bacall outing, but for me it’s their second film, “The Big Sleep” (1946), directed by the inimitable Howard Hawks.

It is, first and foremost, the quintessential private eye picture, along with the earlier Bogart classic, “The Maltese Falcon” (1941). The film succeeds in spite of the fact that its dense, twisty plot leaves most viewers slightly bewildered at the closing credits.

Even the pros making the movie were confused. At one point, Hawks and screenwriter William Faulkner called Raymond Chandler, the author of the book on which the film is based, to inquire just who had killed the chauffeur. “Hell if I know!” was the writer’s laconic response.

All you need to know is that Humphrey Bogart makes private detective Philip Marlowe his own, even though Dick Powell had originated the character in “Murder My Sweet” (1944). Also, the case Marlowe’s on involves blackmail and murder- lots of it.

This movie taught Hawks that logic need not be the primary consideration in telling a story cinematically, if you happen to have dazzling star power and a razor-sharp script (credited to Faulkner, Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman).

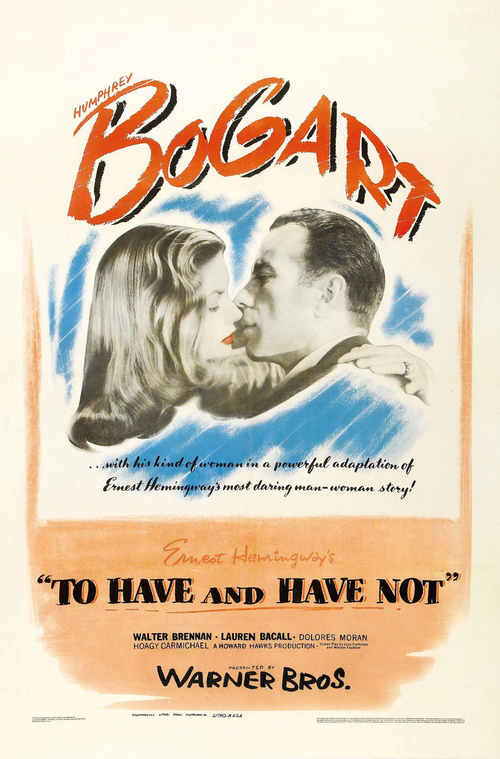

The backstory on this production is rich. The romance between the stars had begun on another Hawks picture, 1944’s “To Have and Have Not” , which was Bacall's film debut. How did she get there? Pure chance. Hawks’s glamorous wife Slim had originally spotted the eighteen-year old beauty on a fashion magazine cover, and told her husband “she’s got something.” He agreed, brought her out to Hollywood for a screen test, and promptly cast her opposite Bogie.

Understandably, Hawks felt highly protective of Bacall — some say he was infatuated with her. So he was livid when she fell into a steamy affair with her leading man, who was both married and twenty-five years her senior. Still, there was little he could do, and privately, he had to admit that Bogie’s infatuation made this normally moody, irascible actor go out of his way to help Bacall deliver a credible performance. Basically, she had no acting experience, and would shake like a leaf before, during and after each take. Bogie became a soothing, reassuring presence.

Now, less than a year later, the couple were starting their second film with the director who’d unwittingly brought them together. The affair had shown no signs of cooling, and as a result, Bogart’s rocky marriage to alcoholic actress Mayo Methot was in its death throes. Conflicted about leaving his unstable wife, Bogie himself was drinking too much, and at one point Hawks had to call him out after one too many scotches over the lunch break.

There were issues on-screen as well as off. Viewing first the rushes and then the final cut, Warner executives became increasingly concerned about Bacall’s performance. Martha Vickers, who plays Bacall’s younger sister in the film, had come through with a highly sensual, attention-grabbing performance; by comparison, Bacall was disappearing into the scenery.

The studio had good reason to be worried and watchful. Though Bacall had scored on her first film, her follow-up, “Confidential Agent,” had been a turkey. She was miscast as an Englishwoman and shared zero chemistry with co-star Charles Boyer. If she didn’t rebound in this picture, her film career could fizzle out fast, Bogie or no Bogie.

The decision was made to re-edit the film, cutting some of Vickers’s scenes and shooting a couple of new sequences that replicated the sexual heat the stars had generated in “To Have and Have Not.” The re-shoot included this exchange between Marlowe and Vivian Rutledge (Bacall), which would become one of the most memorable moments in the movie:

Vivian: Speaking of horses, I like to play them myself. But I like to see them work out a little first, see if they're front runners or come from behind, find out what their hole card is, what makes them run.

Marlowe: Find out mine?

Vivian: I think so.

Marlowe: Go ahead.

Vivian: I'd say you don't like to be rated. You like to get out in front, open up a little lead, take a little breather in the backstretch, and then come home free.

Marlowe: You don't like to be rated yourself.

Vivian: I haven't met anyone yet that can do it. Any suggestions?

Marlowe: Well, I can't tell till I've seen you over a distance of ground. You've got a touch of class, but I don't know how, how far you can go.

Vivian: A lot depends on who's in the saddle.

The re-edited version came out early in 1946, even though most of the film had been shot in 1944 and early ’45. (If you look closely you can see signs of a nation on a wartime footing. Examples include a female cab driver and ration stickers for gasoline). Warner’s was happy to postpone the film's release; by this point they knew the conflict would end soon, and still had a few patriotic war pictures they wanted to put out before they became irrelevant.

Thus the first version of the movie that the studio had fretted about was shown only to troops overseas in 1945. The rest of the public only saw the second version. While the first is less confusing, with more exposition along the way, most viewers agree that the re-edited film is more entertaining. Though some critics voiced frustration at the impenetrability of the story, the public ate it up, as they still do seven decades later.

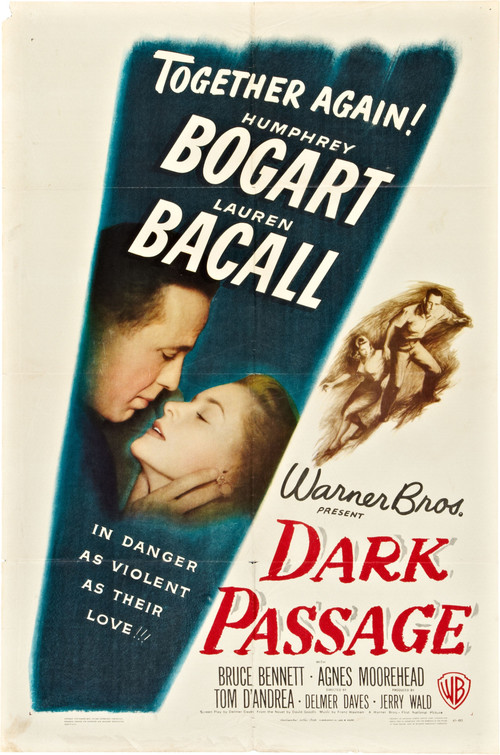

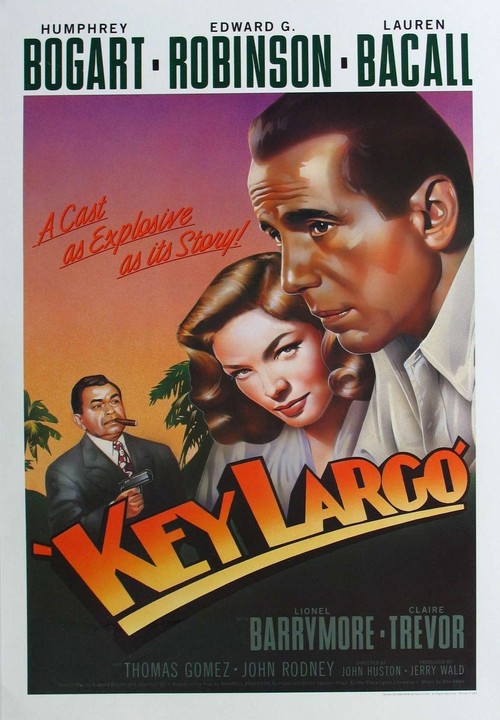

As a result, Bacall was back on top professionally, and her personal life was also on the upswing. She and Bogie were finally married shortly after “The Big Sleep” wrapped. They would make two more movies together before the decade was out — both winners. They’d also make two babies: Stephen, named for Bogie’s character in “To Have and Have Not,” and daughter Leslie, named for the late actor Leslie Howard, who had insisted Bogart be cast in his breakthrough movie role as Duke Mantee in “The Petrified Forest” (1934). Their marriage would last until Bogie’s death from cancer in 1957.

I close with the lines that made Betty Bacall famous at the tender age of nineteen:

“You know you don't have to act with me, Steve. You don't have to say anything, and you don't have to do anything. Not a thing. Oh, maybe just whistle. You know how to whistle, don't you, Steve? You just put your lips together and... blow.”

Thankfully, Bogie whistled.

More: Lauren Bacall's 9 Best Performances