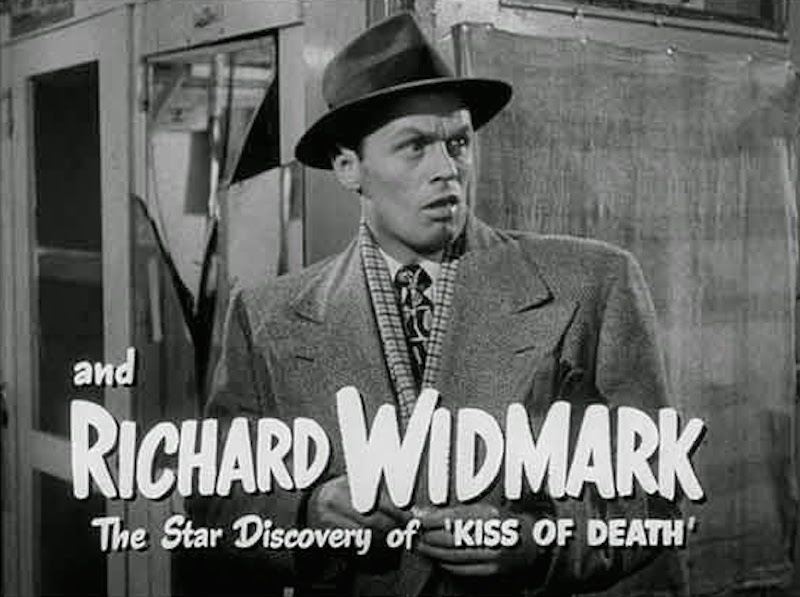

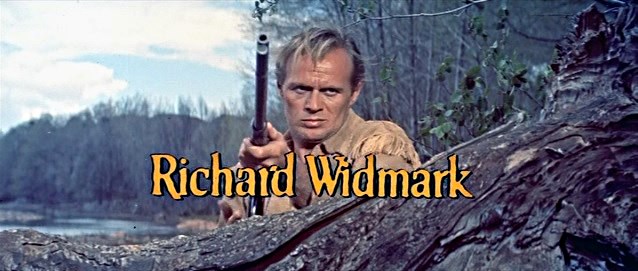

In 1947, a successful young radio actor named Richard Widmark arrived at Twentieth Century Fox in Hollywood to try out for his first film.

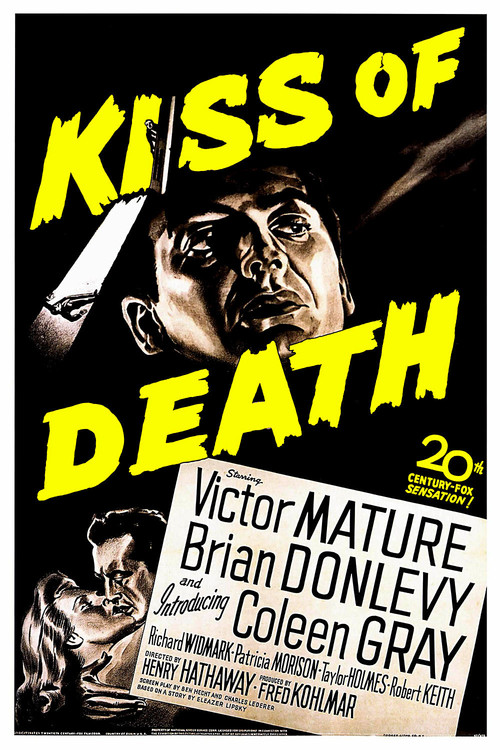

His hope was to be cast in “Kiss of Death,” another in a series of dark crime dramas popular after the Second War which would eventually become known as “film noir.”

The part in question could not have been more at odds with this actor’s mild-mannered demeanor. Widmark was angling for the small but pivotal role of Tommy Udo, a psychopathic killer.

The film’s director, Henry Hathaway, took one look at the actor’s blonde hair and high forehead and pronounced his appearance “too intellectual” for the role. However, studio head Daryl Zanuck recognized a certain nervous intensity in the audition, and overruled the doubtful Hathaway.

Widmark would make the most of his silver screen debut. Screenwriter Ben Hecht helped by giving his character a particularly shocking bit of business to do in the script: tying up a crippled old woman in her wheelchair and then pushing her down a flight of stairs. It would become one of the signature sequences not just in that picture, but in all of film noir. (Trivia note: the wheelchair-bound lady was Mildred Dunnock, who’d shoot to fame on Broadway two years later playing Lee J. Cobb’s long-suffering wife in “Death of a Salesman”).

Widmark had also improvised a nervous giggle for Udo that Hathaway picked up on and encouraged. Years later, the actor recalled his breakthrough role with considerable humor: “I'd never seen myself on the screen, and when I did, I wanted to shoot myself. That damn laugh of mine! For two years after that picture, you couldn't get me to smile. I played the part the way I did because the script struck me as funny and the part I played made me laugh. The guy was such a ridiculous beast.”

Whatever his reasons, that giggle was heard round the world. It had the effect of making Udo that much more frightening to audiences. Thus, on his very first outing, Richard Widmark stole the picture from seasoned players Victor Mature and Brian Donlevy. For his performance, he got an Oscar nod and a Golden Globe. Virtually overnight, he became a movie star.

It could not have happened to a nicer guy. The son of a traveling salesman, Widmark was born in Minnesota but grew up in Illinois. He was smart, conscientious, and well-liked in school, eventually becoming president of his high-school class. He was a star football player, and also excelled at public speaking.

He’d always loved going to the movies. Entering Lake Forest College, Widmark had tentative plans to become a lawyer, but then caught the acting bug. On graduating, Widmark stayed on at Lake Forest for two years to teach speech and drama.

Then a friend suggested that with his deep, distinctive voice, he’d be a natural for radio. He was. Moving to New York City, he was cast quickly and often, and made a good living appearing on some of radio’s most popular programs during its golden age.

But he wanted more, and so started supplementing his radio work with Broadway appearances in the early ‘40s. (A perforated eardrum prevented him from serving in World War Two). Then came the fateful call to Hollywood.

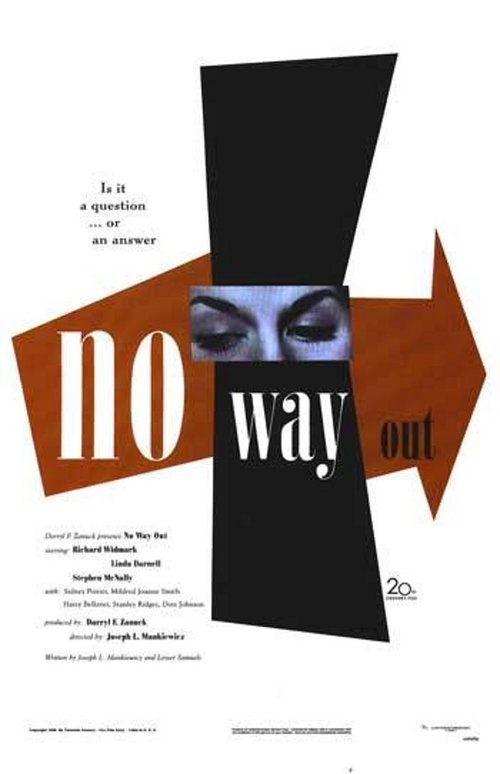

Now under contract to Fox, Widmark’s challenge was to avoid stereotyping. He would be forced to play lowlifes again, but mostly in superior productions like Jules Dassin’s “Night and the City” and Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s “No Way Out” (both 1950).

In the latter film, he plays a deranged racist who hurls epithets at co-star Sidney Poitier’s character. After every offending scene, the kind, left-leaning Widmark would apologize profusely to the young black actor. (The two became lifelong friends, and would collaborate twice more).

Widmark was perceptive enough to know that he was extremely good in villainous roles, but he still wanted to show his range. Eventually he'd play the good guy in a number of films, most memorably a health inspector trying to contain an epidemic in Elia Kazan’s “Panic in the Streets” (1950), and a Nazi war crimes prosecutor in Stanley Kramer’s “Judgment at Nuremberg” (1961).

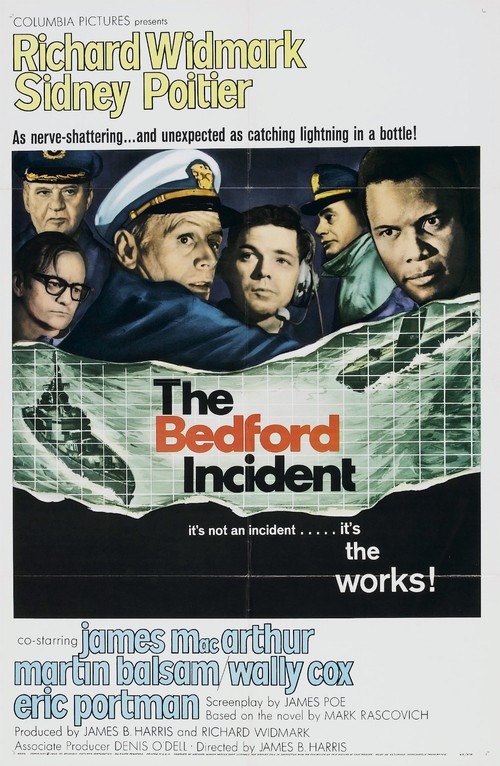

Though he never won another Oscar nod, Widmark’s presence enhanced other indelible films like Samuel Fuller’s “Pick Up on South Street” (1953), “Time Limit” (1957), and “The Bedford Incident” (1965), his final pairing with Poitier.

Widmark had also produced these last two films. He’d gone independent after his Fox contract lapsed in 1954, and soon started his own production company. Seguing to character parts on film and television as he aged, he stayed active in the business until the early 1990’s.

The actor’s personal life mirrored the steadiness of his career. About handling fame, he’d once observed: “I don’t care how well-known an actor is. He can lead a normal life if he wants to.” And that’s precisely what he did.

He had married writer Jean Hazlewood in 1942, and stayed married for 55 years until her death. (Together, they had one daughter, Anne, who was married for a time to baseball star Sandy Koufax). In one interview later in life, he claimed that over that span of time, he had never even flirted with another woman. His reason: “I happen to like my wife very much.”

The couple assiduously avoided the Hollywood limelight, with Widmark once remarking in his characteristically direct, plainspoken way that actors should “do their work and then shut up.” He could not understand the compulsion of some of his colleagues to open up their personal lives to the masses, believing that it “cheapened them as individuals.”

When he was not working, he and Jean would retreat to their private ranch in the appropriately named Hidden Valley. Later, Widmark would also purchase an estate in Roxbury, Connecticut, which is where he spent much of his retirement. (Two years after his first wife died, the actor married Susan Blanchard, Henry Fonda’s widow).

Though he’d often played killers, he was an exceedingly gentle man — and a pacifist — in real life. In his words: “I know I've made kind of a half-assed career out of violence, but I abhor violence. I am an ardent supporter of gun control. It seems incredible to me that we are the only civilized nation that does not put some effective control on guns.” He quietly but generously supported gun-control efforts over the last decades of his life. He also promoted the cause of land conservancy near his Connecticut home.

Richard Widmark died in Roxbury on March 24, 2008, age 93. He’d taken a fall several months earlier, and his condition had worsened over time.

A final anecdote reveals the high regard in which this actor was held. Just as he was retiring back in 1990, Widmark received the prestigious D.W Griffith Award from his old friend Sidney Poitier. Accepting it, he said humbly, “Sid, I can’t believe you came all the way to California to do this for me.”

Beaming back at him with genuine fondness and admiration, Poitier replied: “For you I would have walked!”