Olivia de Havilland’s death not only marks the passing of a great screen actress but also the last vestige of Hollywood’s Golden Age, when the old studio system held sway. In those far-off days, motion pictures, viewed in theaters still owned by those studios, were widely considered the pre-eminent form of mass entertainment.

That albeit imperfect system, undone by the advent of television and a 1948 anti-trust ruling forcing studios to sell their theater chains, produced some of the best movies ever made. And Olivia de Havilland was right in the thick of it.

It’s sad to think that only her death at the advanced age of 104 has made a sizeable chunk of America even aware of her name. Her story — and her best films — richly deserve to be explored and remembered.

I somehow doubt Dame Olivia (she received her DBE from the Queen in 2017) would have called herself a feminist, but underneath her serene beauty and genteel manner lay a tigress who consistently fought for better roles and fairer treatment for herself and her colleagues.

Back in the thirties and early forties, most stars were under long-term contracts to specific studios. The studios picked the films for them, and had authority to loan — or not loan — their services out to other studios. From the start, de Havilland had contempt for the ornamental “girl” roles she was often forced to play at Warner Brothers. Over time she started turning parts down, triggering an automatic suspension. Back then, when a star’s contract was up, studios routinely extended its length to reflect the number of weeks or months the player had been suspended.

When the Warner brass tried applying this so-called rule to her in 1943, Olivia did the unthinkable: she sued the studio. She was told early on that whether she won or lost, her movie career was over. She persevered and eventually won in the courts. The so-called de Havilland Law meant no other actors could have their contracts extended due to past suspensions.

This unlikely trailblazer had a colorful, faintly exotic early life. British subjects by birthright but born in Tokyo, she and younger sister Joan had finally settled with her mother Lilian in Saratoga, California when her parents’ marriage dissolved. (Lilian met and married department store manager George Fontaine soon after).

Lilian occasionally taught drama and music herself, so it was no surprise when Olivia joined an amateur theatrical group at age 16. Her natural talent was quickly recognized. Just two years later, through a combination of luck and ability she found herself cast as Hermia in Max Reinhardt’s production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” at the Hollywood Bowl.

Reinhardt was so impressed with Olivia’s work that he chose her for the film version which Warner Brothers was about to start shooting. Just 18, Olivia signed her first contract with Warner’s. Everything happened quickly after that. The following year she was cast opposite another newcomer, twenty-five-year-old Tasmanian actor Errol Flynn, in a pirate picture called “Captain Blood” (1935). It was a huge hit, elevated by the on-screen chemistry of its two stars. Now just 19, Olivia de Havilland was suddenly famous.

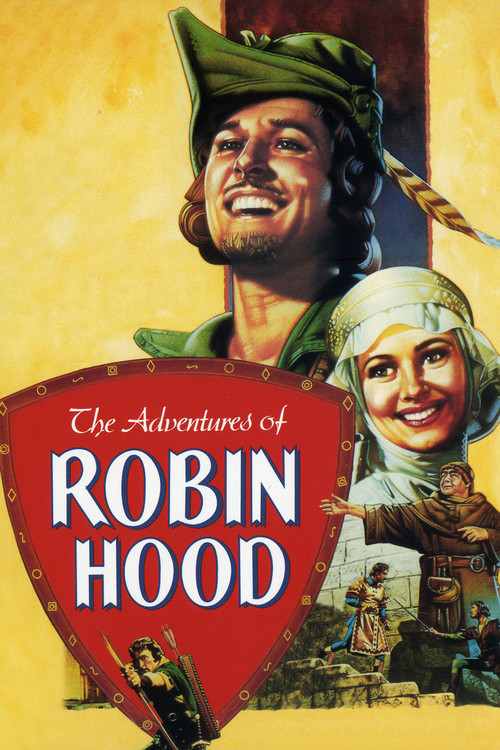

It was no act, by the way: she and Flynn really did like each other, and both considered romance at different times. But the circumstances were never quite right (he was married at the outset, though not for long and never happily). She also noted Flynn’s worsening debauchery and alcoholism as the years progressed, and later expressed relief that they hadn’t acted on their desires. She and Flynn would go on to make seven more movies together in as many years, including 1938’s Technicolor classic, “The Adventures of Robin Hood.”

Despite some squabbles and imposed distance along the way, she’d always hold a special affection for her early co-star and friend. Decades later, having been romanced by charismatic figures like James Stewart, John Huston, and Howard Hughes, de Havilland would still cite Flynn as one of the most charming and magnetic men she’d ever met.

Like the rest of Hollywood in the late thirties, Olivia was caught up in all the excitement surrounding the filming of Margaret Mitchell’s Civil War bestseller, “Gone With the Wind.” Unlike most every other female star in town, she had no desire to play the central role of Scarlett O’Hara, instead believing herself ideal for Scarlett’s kind sister-in-law, Melanie. As she described it: “Melanie was someone different. She had deeply feminine qualities that I felt were very endangered at that time and that somehow should be kept alive. The main thing is that she was always thinking of the other person, and that she was a happy person…loving, compassionate.”

Knowing studio head Jack Warner would resist lending her out to independent producer David O. Selznick for the film, Olivia quietly approached Warner’s wife and enlisted her aid in bringing Warner around. The plan ultimately worked. Today she is best remembered for her sensitive portrayal of Melanie Hamilton, which brought her first Oscar nod.

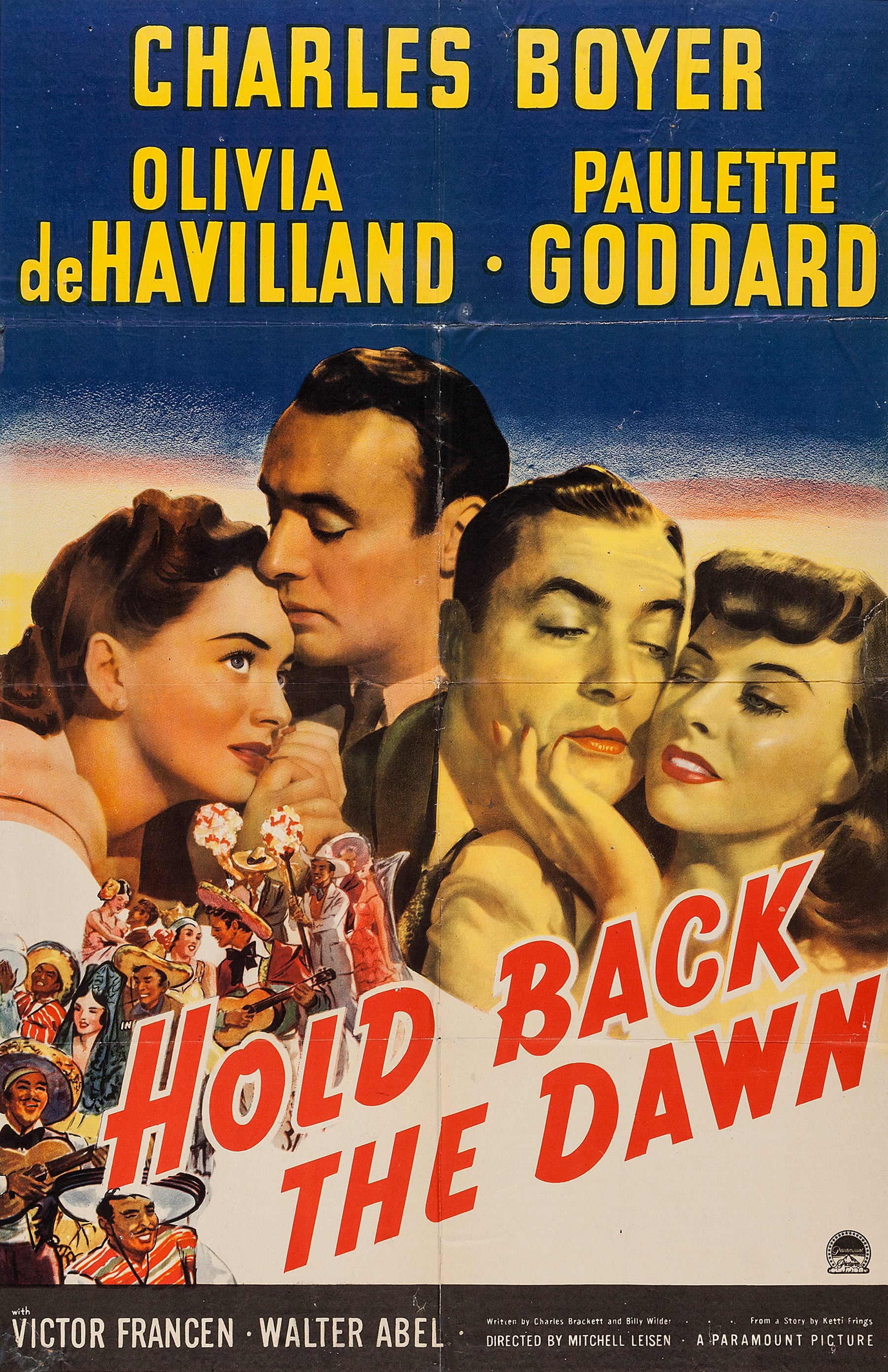

Two years later, on the eve of her adopted country’s entry into the war, she starred in director Mitchell Leisen’s “Hold Back the Dawn,” playing a teacher on a field trip in Mexico who falls for the charms of a mysterious émigré, played by Charles Boyer. For this part, she received her second Oscar nomination (her first for Best Actress).

Famously that year, she lost to her younger sister Joan Fontaine for “Suspicion.” (She and Joan would become the first sisters to be nominated for Oscars in the same year; it happened again twenty-five years later, with Vanessa and Lynn Redgrave).

Taking her stepfather’s last name, Joan had followed her older sister into the business, making a big splash the prior year with another Hitchcock triumph, “Rebecca.” Joan’s win exacerbated a bitter sibling rivalry that had begun very early in their childhood. The sisters’ on-again/off-again feud would become tabloid fodder for years to come.

In 1942, Olivia co-starred with Bette Davis in John Huston’s “In This Our Life,” playing the good sister to Bette’s harridan. It was no secret that Olivia and Huston were already romantically involved when the production began, and viewing the rushes, Jack Warner quipped, “Bette’s got all the best lines, but Livvy’s got the best camera shots!”

A couple of years later, after winning her court case against Warner’s, Olivia became a free agent, finally free to choose her own roles. Arguably her best work as an actress happened over the following decade. First, she’d finally win an Oscar in 1947, having reunited with her favorite director Mitchell Leisen for “To Each His Own”. Here Olivia is an unwed mother who later regrets giving up her baby and is forced to watch her son’s development from afar.

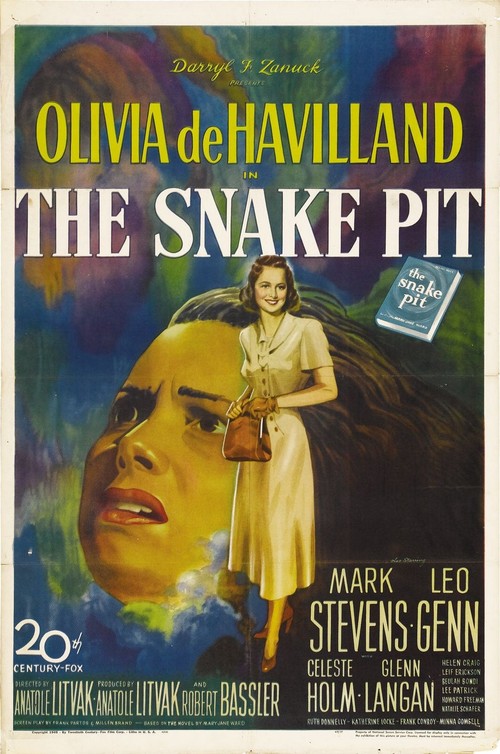

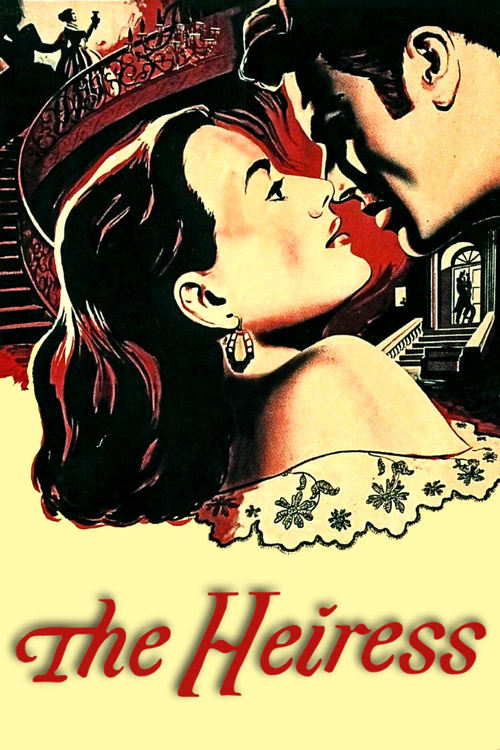

Next she aced demanding roles in two outstanding films back-to-back: first playing a mental patient in 1948’s groundbreaking “The Snake Pit,” and the following year, a wealthy spinster who falls for a handsome but penniless suitor (Montgomery Clift) in William Wyler’s “The Heiress.” This latter performance earned her a second Best Actress Oscar. At 33, she was at the peak of her career.

Of course, for a film actress back then, being 33 meant you were getting on. There were always newer, fresher faces emerging on the scene. And even with two Oscars to her credit, too few really good roles came her way. With the new medium of television suddenly booming, de Havilland may well have sensed that the movie business had seen its best days. And then there was the blunt fact that she had never been truly happy in Hollywood.

1953 brought major changes. Having just divorced her first husband, writer Marcus Goodrich, she traveled to the Cannes Film Festival, where she met Pierre Galante, editor of Paris Match magazine. They married in 1955, and Olivia happily committed to a new life in Paris, leaving Los Angeles far behind. Having had son Benjamin with Goodrich, she gave birth to daughter Gisele in 1956.

Now turning forty with a newborn in a new land, de Havilland settled in and basically returned to acting when she felt like it. Fortunately, she felt like it quite often. Over the next two-plus decades, she appeared in a range of plays, TV shows, and films, notably reuniting with her old friend Bette Davis in 1964 for Robert Aldrich’s shocker, “Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte.” The following year, she became the first woman to head the jury at the Cannes Film Festival.

As she grew older, de Havilland amassed a host of honors, including several honorary degrees, the Medal of Arts from President George W. Bush in 2007, and the Legion d’Honneur from President Nicolas Sarkozy of France in 2010.

She and Pierre Galante divorced in 1979, but they remained close; when he was diagnosed with cancer, she nursed him up to his death in 1998. Happily, de Havilland’s love affair with Paris would endure.

So, of course, will her rich film legacy. We will always remember her because we won't stop watching her best work. Still, her loss moves me to bid a sad, fond, final goodbye to old Hollywood, and its last major player, Olivia de Havilland.