In early 1949, Alexander Korda, the top movie producer in Britain, had cause for excitement. He was about to bring back a winning combination — director Carol Reed and writer Graham Greene — for a thriller that would make history.

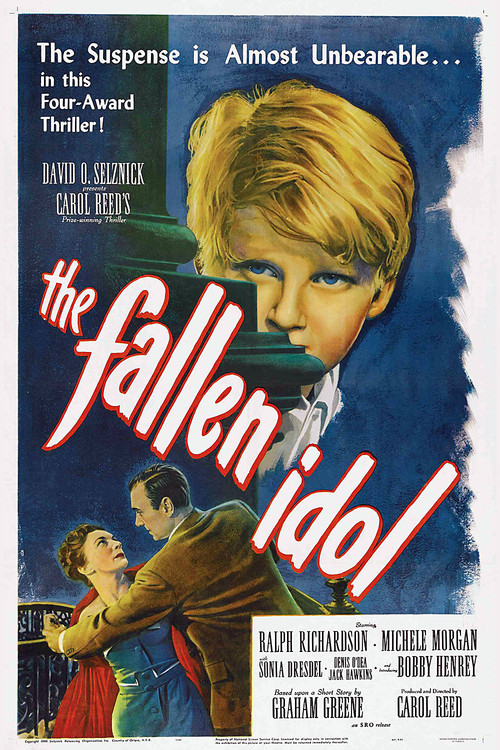

Reed and Greene were fresh off collaborating on another Korda project: “The Fallen Idol,” a moody, literate drama starring Ralph Richardson. The film had been successful, and Korda knew both men respected each other and worked well together. But would lightning strike twice?

This time out, Korda would be partnering with legendary American producer David O. Selznick, famous for bringing “Gone with the Wind” to the screen. This would be a truly international production, with a lot of play in the crucial U.S. market. Thus the stakes were considerably higher.

Selznick was also notorious for interfering on the creative side, something most producers only did sparingly. Both Korda and Reed would have to run interference.

By this point, Selznick was addicted to Benzedrine, so he only got a couple of hours of sleep each night. He had secretaries working around the clock, and his endless memos with “suggestions” to directors were infamous.

This would also be Graham Greene’s first original screenplay, which he decided to draft initially as a novella. He’d draw on some colorful characters from his own early days in the intelligence service to populate his story.

Greene’s protagonist was a failed American writer of Westerns called Holly Martins, who travels to crumbling Vienna when he receives a job offer from his old friend, Harry Lime. On his arrival, Holly is shocked to learn that Lime was hit by a truck and killed while crossing the street.

Yet considerable mystery surrounds Harry’s sudden demise, and Holly decides to do some amateur sleuthing. Soon Holly discovers that Lime was mixed up in some shady black market dealings, and that in fact he may not be dead but in hiding.

Reed originally wanted Jimmy Stewart to play Holly, but Selznick insisted on Joseph Cotten, who was under contract to him. (The producer had also considered Robert Mitchum, but the actor’s recent scandalous arrest for marijuana made that impossible).

With Cotten in the lead, it seemed natural enough to cast his old Mercury Theatre colleague Orson Welles in the small but pivotal role of Lime. As it turned out, Welles would only work a week or two on this film, resulting in about five minutes of screen time.

Later, the actor would jokingly call it the role of a lifetime, since everyone talks about him the whole movie but only sees him at the end. (Given the film’s later success, Welles would sorely regret taking a straight salary rather than the profit percentage he was offered).

Given the pairing of Cotten and Welles and the off-kilter shooting angles reminiscent of “Citizen Kane,” there’s been much speculation about the extent of Welles’s involvement with this picture. The truth is that Welles had very little to do with it, other than some inspired improvisation that resulted in the justly famous line about a “cuckoo clock”.

He was in fact a bit of a nuisance, arriving on the set days late and balking when asked to shoot in the Vienna sewers. The fastidious Welles was terrified about catching some disease. Sets of the sewer had to be built back in England for most of Welles close-ups in the film’s climactic scene, while in Vienna a body double was used for wide shots.

This was very much Carol Reed’s production, and certainly his most ambitious to-date. For a start, it was the first British film shot primarily on location, with Reed inspired by the neo-realist movement then happening in Italy.

Like fellow directors Rossellini, Visconti and de Sica, Reed would use local non-actors throughout the picture to add authenticity and flavor. The director would also inject a noir feel, with liberal use of shadows and reflections of streetlamps in rain-soaked streets.

Reed was usually a slow and methodical filmmaker, but the production had to wrap before the winter snows, so he was on overdrive. He had a daytime unit, nighttime unit, and an all-important sewer unit, and he resolved to direct all three. Taking a page from the Selznick playbook, he got through the shoot with the help of Benzedrine.

Reed won some important disputes along the way. For instance, Selznick wanted leading lady Alida Valli dressed in glamorous clothing throughout the film, but Reed insisted this would look entirely out of place in war-torn Vienna. (Valli plays Anna, Lime’s girlfriend, with whom Holly swiftly becomes infatuated). Selznick grudgingly deferred to him.

Also, Graham Greene wanted the hopeful ending of the novella maintained, where it appears that Holly and Anna may finally get together, but Reed convinced him otherwise. Years later, Greene admitted that Reed’s judgment was spot-on.

The film’s superb supporting cast features Trevor Howard as a suspicious military policeman, and Wilfrid Hyde-White, who’d go on to play Colonel Pickering in “My Fair Lady.” Also look for Bernard Lee, who’d originate the role of “M” in the Bond franchise, as Howard’s loyal assistant. A distinguished group of Austrian and German actors round out the players, including Paul Horbiger as Karl the porter, who spoke no English and had to learn all his lines phonetically.

One of the most famous aspects of “The Third Man” is its distinctive zither score. It came about totally by accident. Initially, Reed was at loose ends about the film’s soundtrack, thinking that a waltz-themed score would be way too obvious. One night, he happened to attend a production party at which the then-unknown Anton Karas was playing the zither, an instrument the director had never heard.

Captivated by the hypnotic sound, Reed hired Karas on the spot and later extended the soundtrack to have his zither music run throughout the movie.

“The Third Man” theme would later become a best-selling record, and with the proceeds, Karas would open a successful Vienna nightclub called “The Third Man,” where he happily spent the rest of his days playing his favorite instrument.

“The Third Man” was a huge critical and commercial hit on release. It received three Oscar nominations, including one for Reed’s direction, and took home a statuette for Robert Krasker’s cinematography. It also won the BAFTA award for Best Film and the prestigious Grand Prize at Cannes.

Among the film’s countless devoted fans are director Martin Scorsese and the late critic Roger Ebert, who said: “Of all the movies I have seen, this one most completely embodies the romance of going to the movies.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.