Gifted writer William Goldman had first come across the true story of Butch Cassidy in the late fifties, and was immediately taken with it.

As he described it: “There is that famous line that Scott Fitzgerald wrote, ‘There are no second acts in American lives.’ When I read about Cassidy and Longbaugh [the Sundance Kid’s real name] and the super posse coming after them—that's phenomenal material…they had a second act...Those two guys and that pretty girl going down to South America and all that stuff. It just seems to me it's a wonderful piece of material.”

Though the story never left his mind, other projects kept intervening, and it took him a full eight years to write the screenplay. (Early on he’d decided not to write it as a book as he wanted to avoid the exhaustive research necessary to accurately portray life in the Old West).

All the studios save one rejected the initial screenplay, and even the studio that showed interest objected to the idea that Butch and Sundance are actually fleeing from the law. The prevailing wisdom with Westerns back then was that heroes — even anti-heroes — simply didn’t do that.

“All I know is John Wayne don’t run away,” said one studio head.

Goldman played the old screenwriter trick of going back and changing a few pages, but keeping most everything intact. All of a sudden he had a lot of takers. In the end, Fox president Richard Zanuck won out, paying a whopping $400,000 for the script, double what he was authorized to offer.

Director George Roy Hill came on board, and Goldman told him he had written the script with Paul Newman and Jack Lemmon in mind. With Hill’s blessing, Newman was approached first. The actor read the script and loved the humor in it, but protested that he was a lousy comic actor.

One of his early flops, 1958’s “Rally ‘Round the Flag, Boys,” had been a comedy, and his performance still appalled him. Hill finally convinced him to accept by assuring him he could and should play his part straight.

Next they went to Lemmon, whose production company had backed Newman’s recent triumph, “Cool Hand Luke” (1967). Ultimately, he passed, citing his dislike for riding horses and a conflict with shooting “The Odd Couple” (1968).

Warren Beatty was approached, but felt the story was too close to “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967). Finally, Steve McQueen read the script and tentatively agreed to do it. However, his agent insisted on first billing for McQueen, and when that was not agreed to, he too moved on.

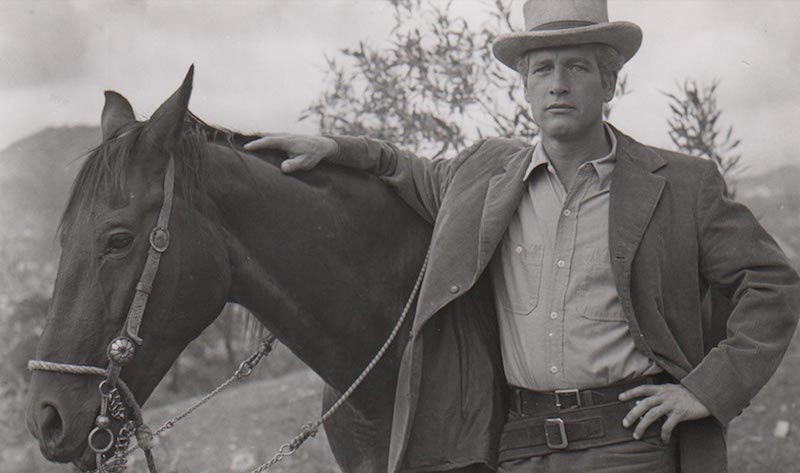

Reportedly, it’s was Newman’s wife Joanne Woodward who raised Robert Redford as an option. Redford, then 32, was definitely an up-and-comer but not yet a big name, with just one starring role to his credit, 1967’s “Barefoot in the Park.”

When Redford eventually signed on to play the Sundance Kid, it felt like a bit of a risk — Hill and Goldman would have preferred two “A-listers” over one for the leads — but that risk would pay off handsomely.

At that point, the film was called “The Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy.” Early on, Newman assumed he’d play the Kid, but Hill persuaded him to take the role of Butch. Given Newman’s box office clout, once Redford was cast the title was swiftly changed to “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.”

The last key role to fill was Etta Place, the Sundance Kid’s lover. When Joanna Pettet had to withdraw due to pregnancy, Katharine Ross, fresh from her Oscar-nominated triumph in “The Graduate” (1967), was tapped.

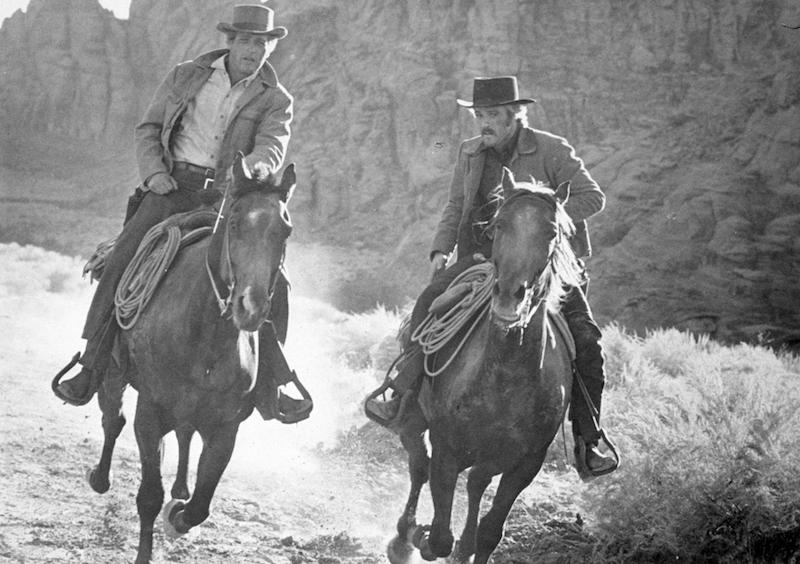

Production began with cast and crew shooting on location in Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. (The later scenes in Bolivia were shot in Mexico). Redford later commented: “We had the best locations possible, to my mind. We had Zion National Park, Durango, Colorado. You rode through that, it was a joy.”

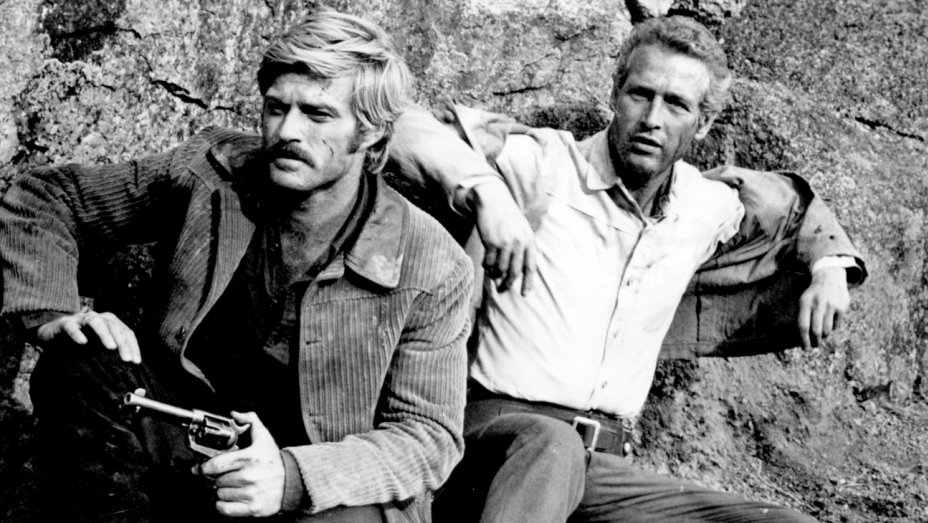

Paul Newman said he had more fun on this production than any other. His quick and easy rapport with his younger co-star helped enormously. He and Redford drank a lot of beer together.

The two men did clash when Redford insisted on doing one dangerous stunt himself, where he runs and jumps on top of a moving train. Newman later castigated him, saying: “I don’t want any heroics around here. I don’t want to lose a co-star.” A chastened Redford agreed to play it safe going forward.

Katharine Ross had a different experience. She was involved at the time with the film’s cinematographer, Conrad T. Hall, and the two would marry that same year. (Coincidentally, her second husband, Sam Elliott, appears in the opening scene, but he and Ross would not actually meet for another decade).

Ross loved the technical side of film. On the first day of shooting Hall found himself short one camera operator for the train robbery sequence, and Ross offered to step in. Hall showed her just how he wanted her to move the camera, and they shot the scene.

When Hill, who was not present, heard about this, he erupted, sending a message back to Ross in her hotel that she was henceforth barred from the set unless she was shooting a scene.

She later said her favorite moment on the film happened when shooting the famous bicycle scene with Newman because the second unit covered it and, in her words, “any day away from George Roy Hill was a good one.” Ross would later describe this production as “very difficult,” and it took her years before she even wanted to see the film.

Back at the studio after location shooting was complete, Hill and Goldman planned to film the New York City sequences using the sets from “Hello, Dolly” on the next soundstage. For a variety of reasons, this was ultimately nixed, so they conceived the famous montage where sepia shots of the three stars are intermingled with actual photographs of New York residents at the turn of the century.

Hill had chosen composer Burt Bacharach to do the score. Bacharach’s sound was very much of the sixties, so he was an unusual candidate for a period film. It was yet another gamble that paid off as the music adds immeasurably to the finished film.

However, when Redford first heard B.J. Thomas’s rendition of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head,” he absolutely hated it, claiming it was completely wrong for the movie. That song, with lyrics by Hal David, would later win an Academy Award.

Goldman was always concerned about balancing the humor in the script with the dramatic elements. At the first preview screening, there was way too much laughter coming from the audience. Concerned about their film being labeled a Western comedy, Hill and Goldman went back and made some judicious cuts.

When “Butch Cassidy” finally opened in the fall of 1969, the reviews were mixed, with Vincent Canby of The New York Times giving it only a lukewarm appraisal and Roger Ebert calling it “slow and disappointing.” Both Hill and Goldman were momentarily bereft.

Soon enough, however, it became apparent that the public loved it. Lines formed around the block at theaters across the country, and “Butch” ultimately became the top-grossing movie of the year. It stands today among the top fifty highest-grossing films of all time.

Nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture, it won four, for Goldman’s script, Hall’s cinematography, and Bacharach/David’s song and score.

“Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” is one of those rare movies whose influence in the popular culture has only grown with time. What makes it endure?

Originally, some critics faulted the film’s anachronistic elements: the modern, clever dialogue and unconventional Bacharach score. I’d argue that these very elements contribute to making the film a uniquely captivating experience. The fact that it doesn’t feel or sound like a traditional Western is part of its magic.

But in the end, I’d submit the key ingredient lies in the charisma of its male stars, and their evident chemistry on-screen. Newman and Redford’s warm, natural interplay throughout the film really carries the whole enterprise. It sent the industry a clear message that the buddy movie did not go out with Hope and Crosby.

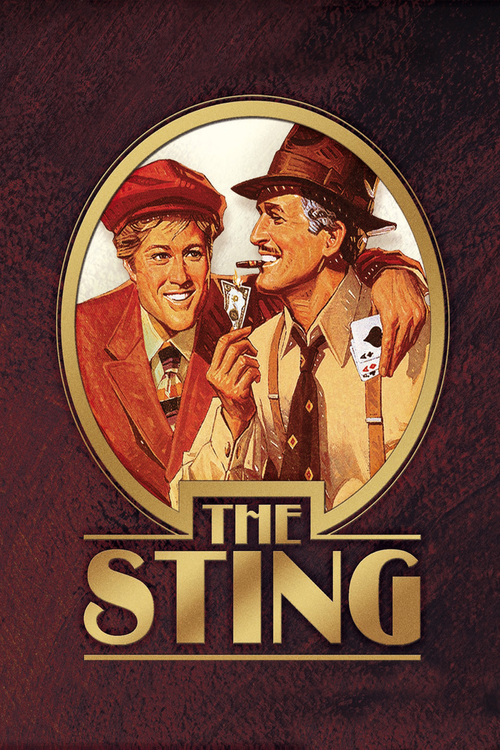

“Butch” made Redford a star and mega-heartthrob, (with my older sister among those hyperventilating); it also showed Newman to be, in fact, a gifted comic actor. Lightning would strike twice four years later when Hill, Newman and Redford re-teamed for “The Sting.” We only wish they’d done even more together.

But then again, we’ll always have Butch and Sundance.

More: Why Robert Redford Will Always Matter