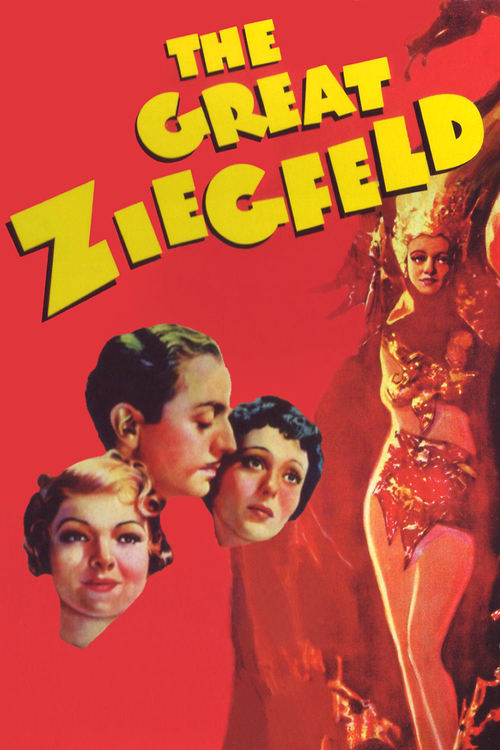

In his hey-day, William Powell was the epitome of sophistication, wit and urbanity, with his distinctive baritone voice, custom tailored suits and pencil thin mustache. During the 1930s and 1940s, Powell was a bona fide box-office draw, starring opposite Myrna Loy as a tippling detective in “The Thin Man” series, as the sly hobo-turned-high society butler in the classic screwball farce “My Man Godfrey,” or in “The Great Ziegfeld,” playing legendary theater impresario Flo Ziegfeld.

But Powell did not just sail into his career as his Nick Charles did into a cocktail. Born in 1892, the Pittsburgh native first considered a law career before studying at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York, which led to stints in vaudeville and theater. His screen debut was in 1922’s “Sherlock Holmes,” starring John Barrymore. A home at Paramount followed, where Powell primarily played heavies.

Then, a breakthrough: Powell’s impressive performance as an egomaniacal director in Josef von Sternberg’s “The Last Command” (1928) helped ease his transition into the sound era. His mellifluous tones and impeccable diction didn’t hurt either. All of a sudden, he was getting lead parts, not villains. He scored as bon vivant sleuth Philo Vance in four films, most notably 1933’s “The Kennel Murder Case,” helmed by Michael Curtiz. (This last title would be on the site, if a decent DVD edition were available.)

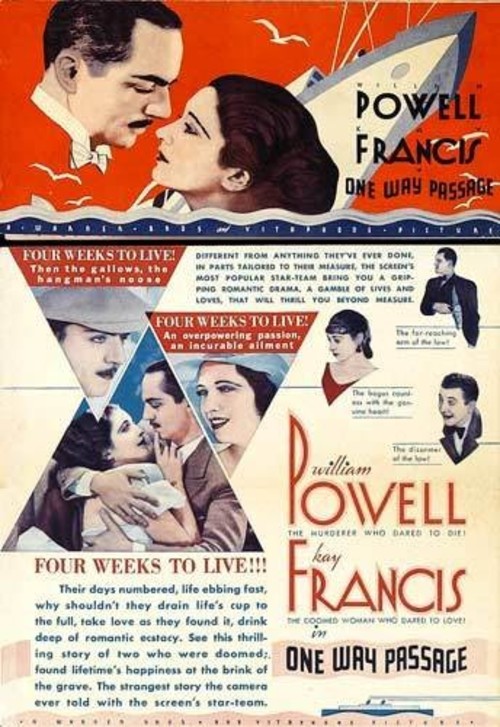

As Powell’s popularity ascended, he shifted studios several times. One thing that didn’t change was his frequent casting with “Thin Man” co-star Myrna Loy; they had wonderful chemistry, and the studio heads knew it. Besides the six “Thin Man” entries, they shared the screen in eight other projects, including “Manhattan Melodrama” (1934) with Clark Gable (famous as the last movie John Dillinger saw before he was gunned down), and “The Great Ziegfeld” (1936), in which Loy played Billie Burke, Ziegfeld’s actress wife.

Other than the first “Thin Man” picture, my favorite Powell-Loy outing is a woefully under-exposed screwball comedy called “Libeled Lady” (1936), in which newspaperman Powell must go incognito and woo heiress Loy so she won’t bring a libel suit against the paper he works for. Spencer Tracy plays the paper’s harried editor, and the stunning Jean Harlow is Tracy’s fiancée, who keeps getting jilted at the altar. The film is fun, fast and smart, with all four leads in top form. (At the time, Powell was also engaged to Harlow. The actress’s sudden, premature death of uremic poisoning at 26 was devastating for Powell, who had flowers delivered to her grave on a regular basis for years.)

1936 was the crowning year of Powell’s career. Sans Loy, he made a big splash in “My Man Godfrey,” opposite former wife Carole Lombard. Undoubtedly, this is the screwball comedy with the most overt social message, reflecting the populist values of the New Deal. At the same, it is impossibly clever, and often hysterical. Powell’s under-playing as a befuddled butler who is not what he seems is nothing short of brilliant, and Powell and Lombard make a superb team. (The two had actually been married years before, but had divorced amicably.)

Godfrey:

The only difference between a derelict and a man is a job.

— “My Man Godfrey”, 1936.

As he aged, Powell wisely eschewed leading man roles, but kept working. Two films in particular stand out in his later career. In 1947’s “Life with Father,” based on a long-running Broadway show, Powell plays the domineering patriarch of an 1880s New York family of four boys, with the ever-graceful Irene Dunne ideal as his scatterbrained wife. Then, eight years later, he would bid the screen farewell as a wise Navy physician in 1955’s “Mister Roberts.” Even while the film mainly showcases the talents of Henry Fonda, James Cagney, and Jack Lemmon, one's eyes still linger on Powell whenever he’s in the frame.

After that, Powell declined efforts to lure him back to the movies, and spent his remaining years living quietly with his third wife Diana Lewis in Palm Springs, California. Typical of him, he had made a graceful, well-timed exit. When William Powell died on March 5, 1984 at the age of 91, Hollywood lost one of its most debonair stars, thoroughly believable and at ease playing a detective, a doctor or a drifter.