Frank Pavich’s documentary, “Jodorowsky’s Dune,” tells the remarkable story of director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s failure to make an adaptation of the sci-fi classic, “Dune.” But it’s also about the eternal conflict between art and commerce in Hollywood, and what can happen when an artist’s uncompromising vision of a film causes those opposing forces to collide.

In the end, what was to be Jodorowsky’s crowning achievement instead became a heartbreaking episode that truncated his career as a director.

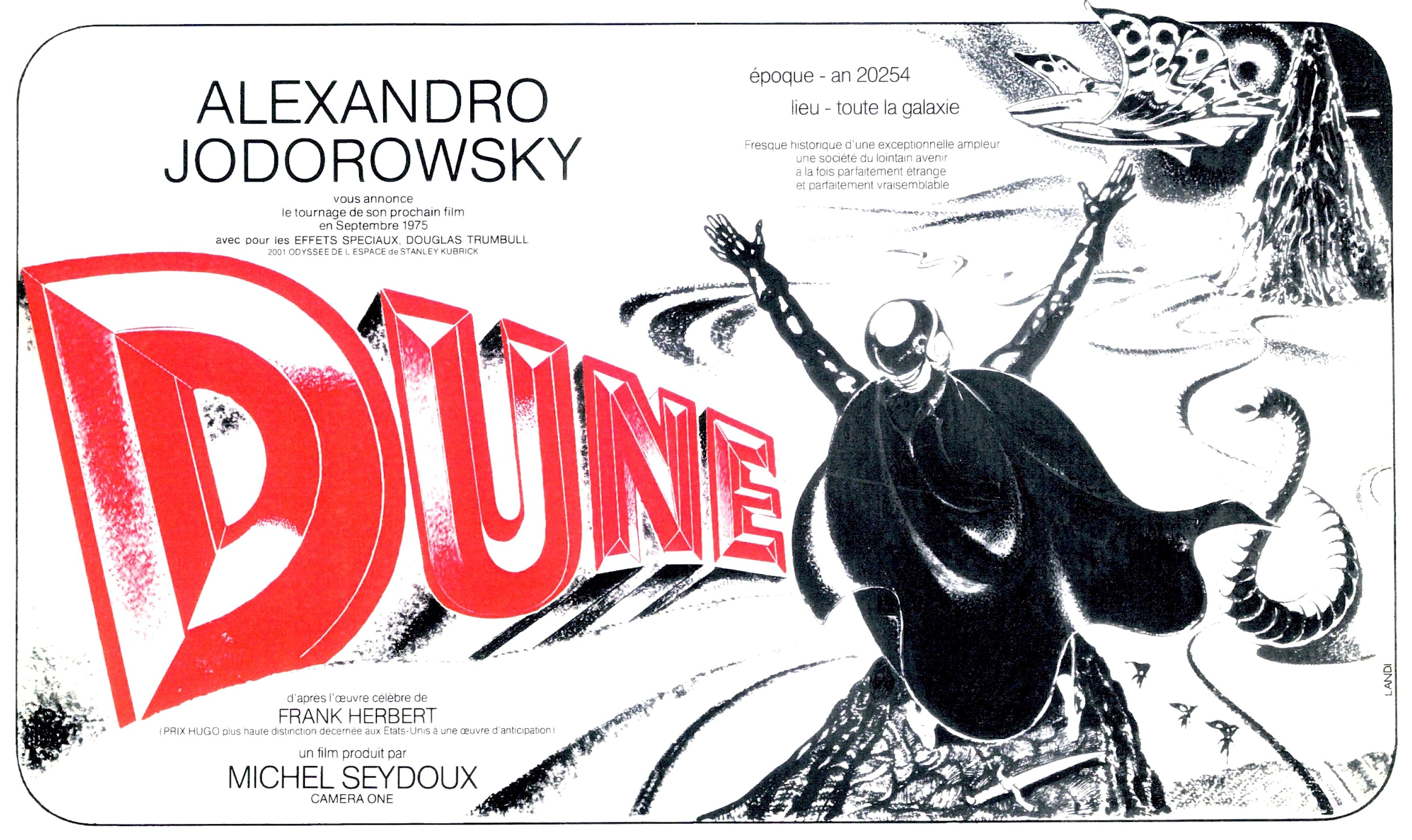

The director and his producing partner, Michel Seydoux, had secured the rights to Frank Herbert’s wildly popular book and raised about $10 million to produce it. Jodorowsky was ecstatic, even manic. He scoured Europe for the finest artists to visualize the narrative he had pouring out of his mind. Every character, costume, spaceship, and set was meticulously designed and catalogued.

He tracked down celebrities like Mick Jagger, David Carradine, Orson Welles, and even the famous Surrealist painter, Salvador Dali, to play key roles. They all said yes, though Welles and Dali made Jodorowsky sweat before they agreed.

Welles (who at this point preferred stuffing his face to rehearsing lines) only relented when he was promised that lunch would be catered by his favorite five-star restaurant.

Dali was a trickier sell – he wanted an interesting story to tell at dinner. He said he’d do it, but only if he could be paid more than any actor had before him. Seydoux came up with an ingenious solution: since Dali would only be on-screen for a few minutes, they’d pay him the highest salary ever, but by the minute. Dali assented and got his cocktail conversation piece.

At an expense of nearly $2 million, the team delivered a stunningly detailed shooting script to major Hollywood studios, who Jodorovwsky hoped would fund the last few million they needed to shoot. The brass took a long look at the complexity of the production, the length of the script, and the man who would shoot it, and promptly rejected it. Why? For starters, the first cut would’ve run an unmarketable ten hours.

Half a century earlier, the same issue ruined the career of another filmmaking visionary named Eric Von Stroheim. Stroheim created a picture called “Greed.” It was so long, theaters would’ve had to serve lunch and dinner to their dazed audience. The studio money men saw in Jodorowsky what their predecessors had glimpsed in Von Stroheim: a fervent, almost religious vision that would brook no negotiation about what went up on the screen. They turned the other way and ran.

Besides the money issue, Jodorowsky’s films to-date were an acquired taste (certainly catnip for LSD fans). Watch a few minutes of his “El Topo” (1970) or “The Holy Mountain” (1973), and you’ll get the idea. Undeniably, they’re works of art – bizarre, surreal, filled with symbolism – but they follow no traditional narrative. Deep and distinctive as his prior work was, it didn’t follow the formula for success that Hollywood demanded.

Thus, Seydoux and Jodorowsky flushed away millions of dollars, mega-producer Dino De Laurentis swooped in to snag the film rights, and Hollywood hired David Lynch to make their own middling version of “Dune.” Jodorowsky’s only consolation was that the resulting film tanked.

“Jodorowsky’s Dune” makes you wish the original director’s version had been made. Lord knows, we could use a few more risk-takers in the business- some creative pioneers interested in advancing the form, not milking a formula.

Alejandro Jodorowsky could have been such a man, but sadly, he stood alone.