It’s sad but true that the bygone film directors we tend to remember are those associated with specific types of films (think Hitchcock for suspense and John Ford for Westerns), while the more versatile players often get lost in the fog.

When most people think of George Cukor, for instance, they may recall one or more of his finest films, or that he was known as a “woman’s director” — an observation he resented, and for good reason. It was limiting, while Cukor’s talent was virtually limitless.

The description could also be read as a subtle reference to his homosexuality, which was widely known in the industry, though only spoken of in whispers. In his prime, Cukor was famous for hosting lavish parties where he cultivated some of the biggest names in the arts, including Noel Coward, Cole Porter and Somerset Maugham.

When they all went home, a group of young men would arrive, and yet another party would begin. This was hardly a secret, and in those repressive times, Cukor had to walk a very delicate line to protect his career.

Fortunately, his widely acknowledged brilliance as a director protected him. When he was arrested on vice charges at the height of his career, the all-powerful MGM studio made it all go away. There was too much invested in him.

The son of Jewish Hungarian immigrants, George Dewey Cukor was born in New York City in the summer of 1899. George’s father was educated and lived out the American Dream as an Assistant District Attorney.

It was initially assumed that George would follow his father into the law, but the sensitive young boy took after his mother Helen, who had artistic leanings. One of Cukor’s earliest, most vivid memories was watching her at parties, donning costumes and imitating famous personalities of the day. It was his introduction to the world of make-believe, and he was hooked.

After briefly enrolling at City College, George quit to become an assistant stage manager with a play on tour. His ascent in the theater world would be swift. Over the next several years, he rose to stage manager, then general manager of several traveling troupes.

In 1925, he formed his own theatrical production company which gave him his first chance to direct. The group of stock players he collected included Louis Calhern, Frank Morgan, and Reginald Owen… also a young player named Bette Davis, who supposedly chafed at Cukor’s direction so much that he was forced to dismiss her. She never forgave him for it.

In 1926, George directed a stage adaptation of “The Great Gatsby” on Broadway, which won critical raves. He’d direct six more Broadways plays over the next three years.

With the coming of sound pictures, the Hollywood studios needed theatrical talent who could teach their stars how to speak. Paramount hired Cukor, paying for his airfare and giving him a starting salary at least double what he was making in the theatre.

He first became a dialogue director, and in the fall of 1929, George was lent out to Universal Studios to handle screen tests and dialogue coaching for “All Quiet on the Western Front.” He also started directing and saw his salary virtually tripled. He was settling in nicely.

It was at this time that George got acquainted with up-and-coming producer David O. Selznick. After an unpleasant collaboration with Ernst Lubitsch on “One Hour with You” (1932), Cukor decided to follow Selznick to RKO, where the thirty-year-old wunderkind had just been named head of production.

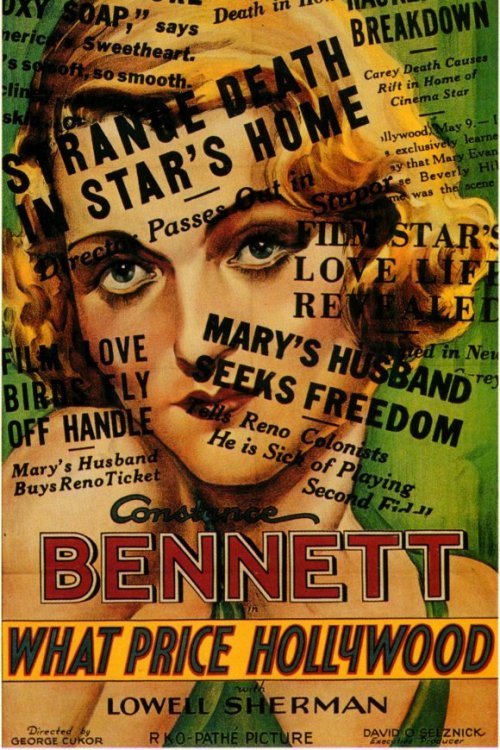

This marked the beginning of a creative partnership that would yield some of the best films of the decade. At RKO, the two collaborated on such films as “What Price Hollywood?” (1932), and “A Bill of Divorcement” (1932), a drama that marked the film debut of a young actress from the east named Katharine Hepburn.

In 1933, Selznick moved once again to MGM, and was given his own production unit. This seemed fitting since he’d just married studio head Louis B. Mayer’s daughter, Irene. Cukor wisely followed, and their string of successes continued.

After the fabulous ensemble piece, “Dinner at Eight” (1933), a series of glossy, literate period pictures followed, notably “Little Women” (1933, reuniting Cukor with Kate Hepburn), “David Copperfield” (1935), “Romeo and Juliet” (1936), and “Camille” (1936). All were successful, burnishing MGM’s reputation as “the Tiffany of studios.”

It was only natural that Selznick would then tap George to helm his most ambitious production to-date, the screen adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s “Gone with the Wind.” What could have been the pinnacle of their highly productive association instead became its undoing.

Many explanations have been offered for the rupture. Two stand out as credible: first, Selznick had always exerted an unusual amount of control as producer and never more so than with this film, in which his reputation was so heavily invested. This caused increasing tension with Cukor, particularly when the two had serious differences on the script.

But the true breaking point was Cukor’s relationship with Clark Gable. It has been widely reported that the star was homophobic, not an unusual attitude for the time. Part of Gable’s discomfort may also have involved a long-buried secret from his own past: a rumored one-time homosexual encounter with close Cukor friend Billy Haines over a decade before, when Haines was a big silent star and Gable was still struggling for a foothold.

Citing the fact that Cukor “was throwing all the scenes to the women,” Gable demanded that George be replaced with the more macho Victor Fleming. Selznick ultimately sided with Clark, and Cukor was fired. (He promptly went off and made “The Women,” a catty comedy with an all-female cast that holds up beautifully to this day). Still, he and Selznick would never work together again.

The same could not be said for Kate Hepburn. Cukor had swiftly become her director of choice, and they’d make eight more pictures after “Women,” four in the following decade: “Sylvia Scarlett” (1936), “Holiday” (1938), “The Philadelphia Story” (1940), and “Keeper of the Flame” (1943).

Though a notorious flop on release, “Scarlett” marked the first of four Hepburn pairings with Cary Grant, and is now considered the film that first displayed the handsome actor’s range and flair for comedy. “Flame,” meanwhile was Kate’s second outing with Spencer Tracy, who would become her lifelong partner. (The two had met the year before on the set of their first film, “Woman of the Year”).

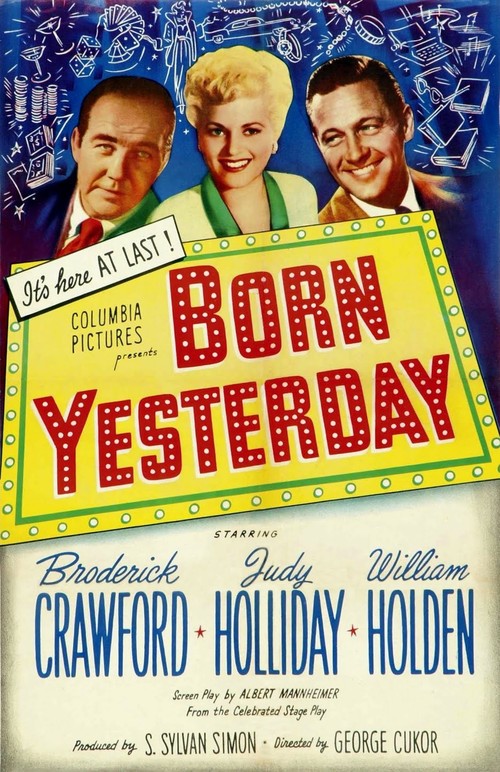

Kate was hardly the only Cukor loyalist; many stars he directed wanted to work with him again. After “Camille,” Garbo wanted him for her last film, “Two-Faced Woman” (1941). After “Romeo and Juliet,” he reunited with Norma Shearer for “The Women.” Preeminent actor Tracy would collaborate with Cukor four times, once without Hepburn (1947’s “Edward, My Son”). And finally, after launching her film career in “Adam’s Rib” (1949), he’d work again with Judy Holliday on both “Born Yesterday” (1950) and “It Should Happen to You” (1954).

In 1954, George got the chance to direct his first color film and first musical, “A Star is Born” (1954), remaking the 1937 classic directed by William Wellman. It would be a bittersweet experience. The vastly talented Judy Garland was cast as Vicki Lester, an aspiring singer/actress who becomes involved with alcoholic star Norman Maine (James Mason), and sees her career rise while his falls.

This would be a comeback of sorts for Garland, who’d been fired from 1950’s “Annie Get Your Gun” for erratic behavior stemming from her pill addiction. She had not done a film since. Cukor had worked with her briefly on “The Wizard of Oz” fifteen years before, coaching her into a more naturalistic performance and doubtless thought he could handle her.

Though Judy was focused and disciplined at the outset, she soon fell back into old, self-destructive patterns, and her frequent absences resulted in significant production delays. Worse yet, the first cut of the film was over three hours and the Warner executives dictated significant trimming over Cukor’s strenuous objections. He could not bring himself to watch what ended up in theaters. Sadly, the film lost money on release, though it’s since been hailed as a classic.

Cukor would stay busy into his sixties, but with the exception of 1957’s “Les Girls,” he would not make another outstanding picture until he won the assignment to direct yet another musical — the screen version of “My Fair Lady” in 1964. It was, of course, a triumph. After receiving four Best Director Oscar nominations over thirty years, he finally got his statuette for “Lady,” which also garnered seven other awards, including Best Picture.

Many other directors hitting retirement age would have viewed this as the perfect swansong, but not George. He still projected the energy and enthusiasm of a much younger man, and he loved directing. In the coming years he made the occasional film and kept advancing ideas that weren’t picked up by the studios. Ironically, after perhaps his biggest success, Cukor felt increasingly sidelined.

There was, of course, a fundamental explanation for this: with the studios now losing money on the types of films that had worked before, change was in the air. Titles like “The Graduate” and “Bonnie and Clyde” heralded new players and fresh approaches to filmmaking. And if anyone represented the old school, it was George Cukor.

Nevertheless, he’d manage to work twice more with his old friend Katharine Hepburn, on “Love Among the Ruins” (1975) and “The Corn is Green” (1979). Two years later, he’d make his last film, “Rich and Famous,” a remake of the Bette Davis-Miriam Hopkins hit “Old Acquaintance” (1943).

George Cukor died of heart failure on January 24, 1983. He was as old as the century he’d done so much to enhance. Years earlier he’d mused that had he been better-looking, he might have become an actor. His many loyal fans are eternally grateful that he chose to place himself behind the camera instead.