One early movie-going experience I’ll never forget: at the tender age of 11, I was peering up at an immense screen in one of Manhattan’s grand old cinemas. I was there to see a newly released film called “Patton.”

The lights went down, and before any credits or music, an American flag filled the screen. An imposing man in uniform ascended some stairs to a platform and began speaking to an unseen audience of soldiers. As this opening scene progressed, I was struck by this man’s power, confidence, and authority. His was a fearsome, awe-inspiring presence.

This was my introduction to gifted actor and director George C. Scott.

I became a fervent fan and follower, and in the years to come, was lucky enough to see him on the Broadway stage several times (first in “Sly Fox,” then many years later in “Inherit the Wind”). He radiated the same outsize intensity in person.

Of course I familiarized myself with all his best film work, most notably his hilarious turn as General Buck Turgidson in Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant Cold War satire, “Dr. Strangelove: or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (1964). Though it was Peter Sellers who was Oscar-nominated for playing three distinct parts in the movie, I’ve always felt Scott (and Sterling Hayden) stole the show.

Scott’s magnetism always contained an undercurrent of anger, conflict and pain. Born in Virginia, George lost his mother at eight, and was raised by his father, an executive at Buick. After high school, he ended up in the Marine Corps, stationed in Washington, DC. He ended up being assigned to the burial detail at Arlington Cemetery, a relentlessly depressing duty which exacerbated his innate melancholy and started him drinking.

After his time in the service, George attended the University of Missouri, where his love of the written word first drew him to journalism. Then he discovered acting, and in it found not only a natural affinity, but a welcome distraction from his own inner demons. Acutely self-aware, Scott would later say: “It was the only avenue of escape I had from myself. It's never been difficult to subjugate myself to a part because I don't like myself too well. Acting was, in every sense, my means of survival.”

After graduating from college, Scott pursued his calling single-mindedly, and ended up in the theatrical Mecca of New York City. Hired by Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival, he drew the notice of critics in a 1957 production of Shakespeare’s “Richard III.” The next year he’d win an Obie Award, and appear on Broadway as the prosecutor in “The Andersonville Trial.”

At the same time, George was beginning to get parts on television and in film. After his debut on the big screen in 1958’s “The Hanging Tree,” he was tapped by director Otto Preminger to play (once again) a prosecutor in “Anatomy of a Murder” (1959). His performance brought him his first Oscar nomination. At age 32, George C. Scott had arrived.

By the time “Patton” came along a decade later, Scott was an established star. However, he wasn’t the first choice to play the famous General. Burt Lancaster, Robert Mitchum, Lee Marvin and Rod Steiger had all turned down the role.

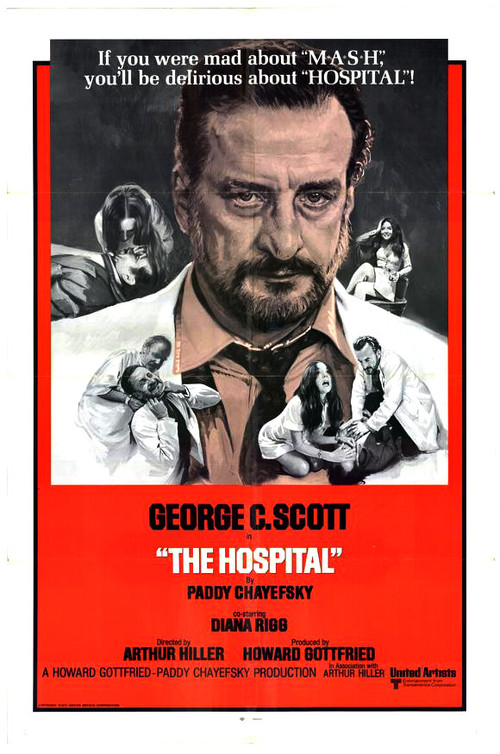

Scott approached the part with the same discipline he brought to all his work, researching every aspect of Patton’s life and character. Whether he realized that this could be his defining role is unclear. Reportedly, he was ambivalent about doing the picture, believing it reflected the myth of Patton more than the real man. Later, he recoiled at all the hoopla that accompanied the film’s release and became the first actor ever to turn down an Oscar, referring to the ceremonies as a “meat parade”. (It hardly seemed to matter to the Academy, who nominated him again the very next year for “The Hospital”.)

Again, Scott’s ambivalence about achieving fame in his chosen profession had much to do with this reaction, along with the conviction that every performance was unique and should not be judged relative to others. Revealingly, he once said: “There is no question you get pumped up by the recognition. Then a self-loathing sets in when you realize you're enjoying it.”

When working, he could be imposing and moody. One one occasion, his Broadway co-star in “Plaza Suite,” Maureen Stapleton, confided in director Mike Nichols that Scott terrified her. The director soothingly replied, “My dear, everyone is afraid of George C. Scott!”

The actor’s personal life reflected the restlessness and turbulence of his own character. His five marriages-and one relationship out of wedlock- resulted in seven children. Perhaps his most fiery and famous union was with fellow actor and stage co-star Colleen Dewhurst; they actually married twice. (One of their two children is actor Campbell Scott.)

Happily, George’s last marriage, to Trish Van Devere, endured for over 25 years, and the couple appeared in a host of movies together, including “Movie Movie” (1978) and “The Changeling” (1980). Still, they chose to separate for a while, and once reconciled, lived in different places most of the time — she on the West Coast, he in Connecticut.

Starting in the 1980s, all the years of hard work and hard living began catching up with Scott, and he suffered several heart attacks. He would never regain his health, and looked much older than his years, even as he stayed busy. George C. Scott finally succumbed to an aneurysm in 1999, aged 71. It was too soon.

Few know it, but Scott formulated one of the most succinct definitions of great acting I’ve ever heard: “[Acting] technique is making what is absolutely false appear to be totally true in a manner that is not recognizable.”

He not only spoke these words; he bore them out in every performance he gave.