Over a period of fifteen months from the beginning of 1931, the Warner Brothers studio released three bona fide gangster classics: “Little Caesar,” “The Public Enemy,” and “Scarface: The Shame Of A Nation.”

All three movies made stars out of their leading men in the still fledgling sound era: Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, and Paul Muni.

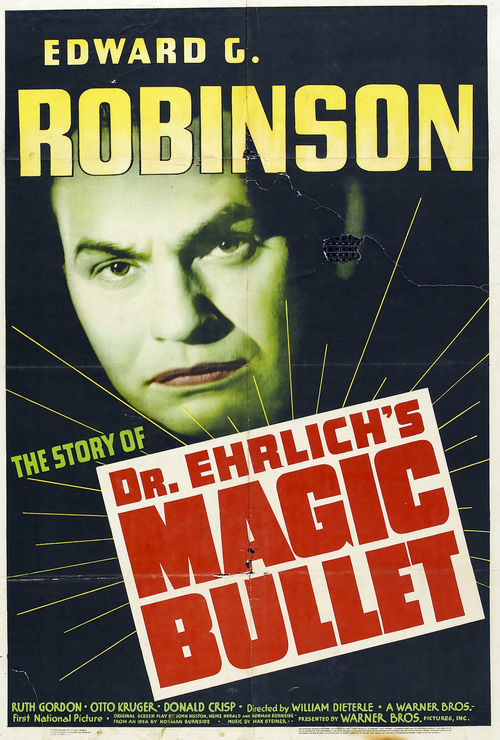

Of these three movies, “Little Caesar” was the first to reach the public, and it caused a sensation. Organized crime was still a fairly recent phenomenon, its dramatic growth fueled by Prohibition. The film's boldness in confronting this scourge head-on was considered daring at the time.

“Caesar” was indeed blunt, brutal and electrifying, projecting the gritty realism that swiftly became the studio’s trademark. Still, much of the movie’s impact came from Robinson’s powerfully menacing portrayal of mobster Rico Bandello.

Robinson was an unlikely star at first glance. Dark, short, stout and considerably less than handsome, he seemed anything but the typical leading man. But on-screen his magnetism was undeniable. If he was in the frame, you looked at him and no one else.

In real life, he was the opposite of his tough guy screen image: a gentle, quiet, cultivated man who collected impressionist paintings and who, in his youth, had considered becoming a rabbi.

He was born Emmanuel Goldenberg in Bucharest, Romania, but his family emigrated when he was just ten, ending up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. His aptitude for dramatics was noted several years later, and he won a scholarship to study acting.

He first worked in Yiddish theater, then graduated to Broadway, while winning the occasional minor part in silent films. By this time, he’d changed his name to Edward G. Robinson (with the “G” standing for his real surname).

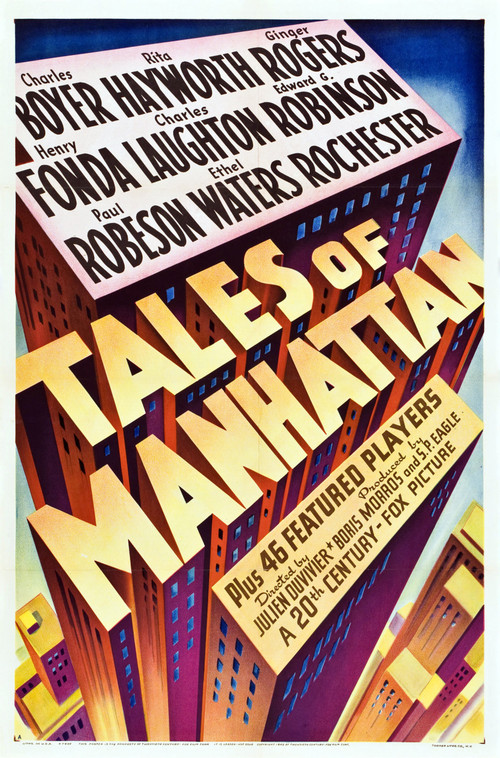

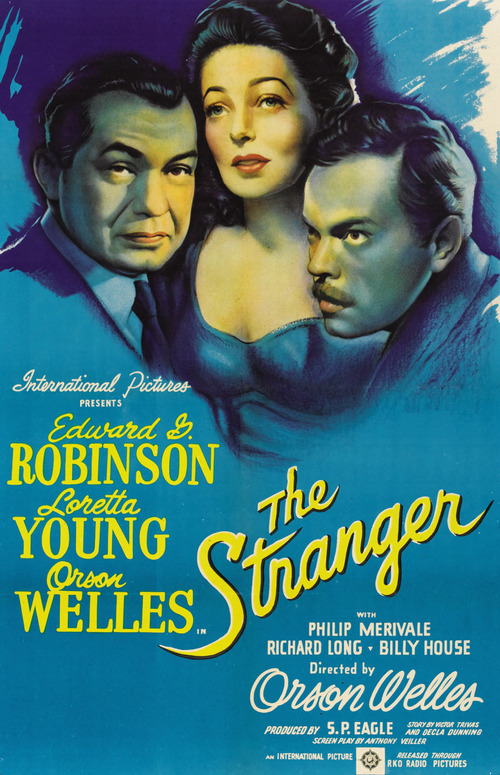

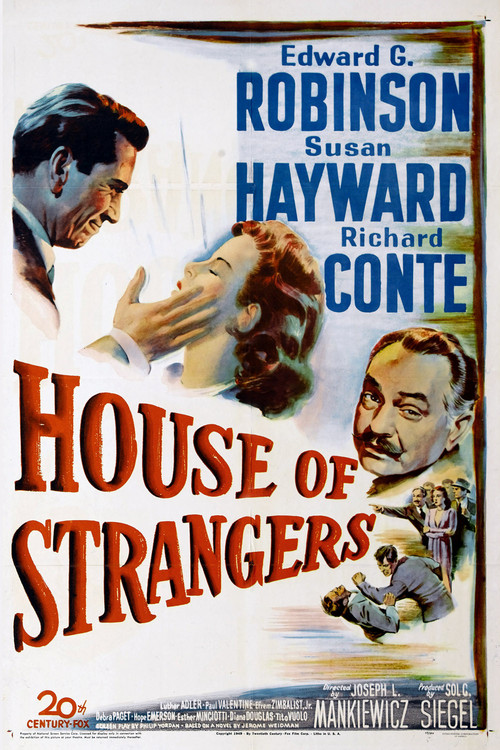

After the success of “Little Caesar,” Robinson became one of the top Warner stars in the ‘30s and ‘40s. It’s incredible that he was never Oscar-nominated when you consider some of the parts he played: most notably, a dogged insurance investigator in Billy Wilder’s “Double Indemnity” (1944), a naïve man ensnared by villainess Joan Bennett in Fritz Lang’s “The Woman In The Window” (1944), and yet another mob boss in John Huston’s “Key Largo” (1948). These key roles reflected the actor’s virtuosity and range: he could play good guys and bad guys with equal skill.

Politically, Robinson was a liberal and — no surprise — an outspoken critic of fascism. His left-wing politics would come back to bite him. During the Communist witch hunts in the early fifties, he appeared as a friendly witness in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Though he cleared himself and named no names, offers of work slowed considerably. By the time he divorced his first wife in 1956, Robinson had to sell his precious art collection to pay for the settlement.

Thankfully, within several years his career had rebounded, and he continued working in movies (and occasionally television) right up to his death from cancer in 1973. He was 79.

Just a couple of months before he died, Robinson learned he’d be receiving a special Oscar for lifetime achievement. He didn't live long enough to accept it. The tribute in part read: [he]…achieved greatness as a player, a patron of the arts, and a dedicated citizen ... in sum, [he was] a Renaissance man.”

Clearly Edward G. Robinson was as revered off-screen as on-. Reflecting the keen mind and thoughtful approach that informed his work, he also offered one of the most succinct descriptions of how to succeed as an actor: “To last you need to be real.”

Eddie G. — you were always real.

More: Crime Does Pay — 10 Gangster Movies Worth Watching Tonight