I will always remember my middle son’s devotion to Doris Day movies when he was very young. This otherwise very rough-and-tumble kid would look at me on a rainy Saturday afternoon and ask quietly, “Got any more Doris?”

This always amused me. I couldn’t help thinking that Doris Day seemed so far removed from the 21st century, belonging exclusively to that bygone era of clean movies, saccharine songs, and prescribed gender roles.

But of course I was underestimating her, and her impact. My young son saw something very special that millions of others did and still do. On the one hand, Doris was the woman you could bring home to your mother. Yet underneath that sunny, seemingly wholesome exterior was a very strong and sensuous lady who knew what she wanted and could take care of herself. You could well understand what Rock Hudson, Cary Grant and James Garner saw in her.

Many forget just how popular she was. Though her last movie was released nearly half a century ago, she remains on the top-ten list of all time box-office stars. Between 1960-1964, she was the top box-office draw in the movie business, and the only woman in the top-ten. And she was almost as big in the music business — a vocalist with a fan base to rival Ella Fitzgerald and Judy Garland.

She was born Doris Mary Ann Kappelhoff in 1922, the youngest child of a music teacher and housewife. Growing up in Cincinnati, her first ambition was dancing, but a car accident in her teens put an end to that. Recuperating in bed, she began singing along with the radio, and discovered she had another talent. Soon she was taking voice lessons.

At the age of seventeen, she got her first serious job as female vocalist in a touring band. Thinking her last name was a mouthful, the bandleader re-named her “Doris Day.” At age 23, she recorded her first hit, “Sentimental Journey,” a song that serenaded our GI’s home. More bands and hits followed.

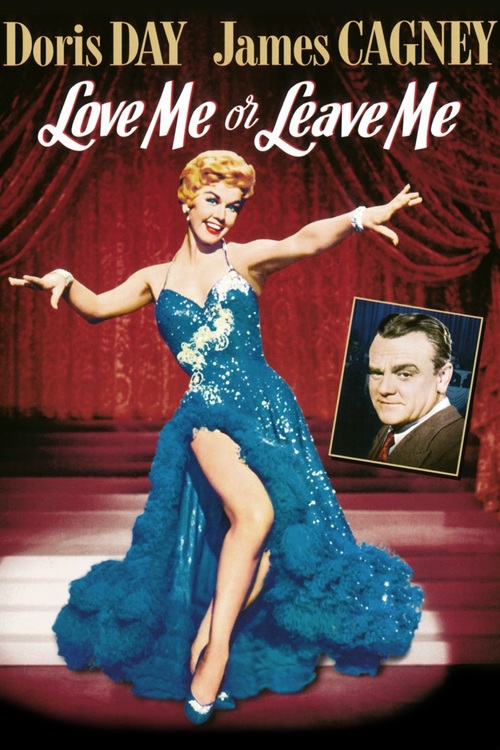

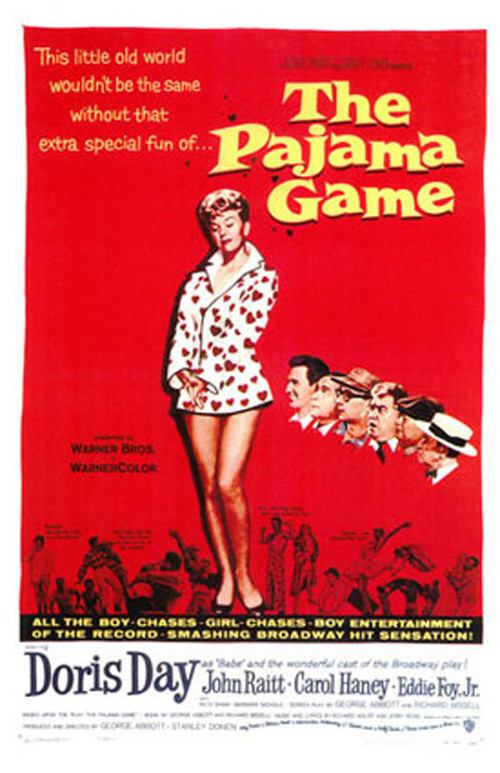

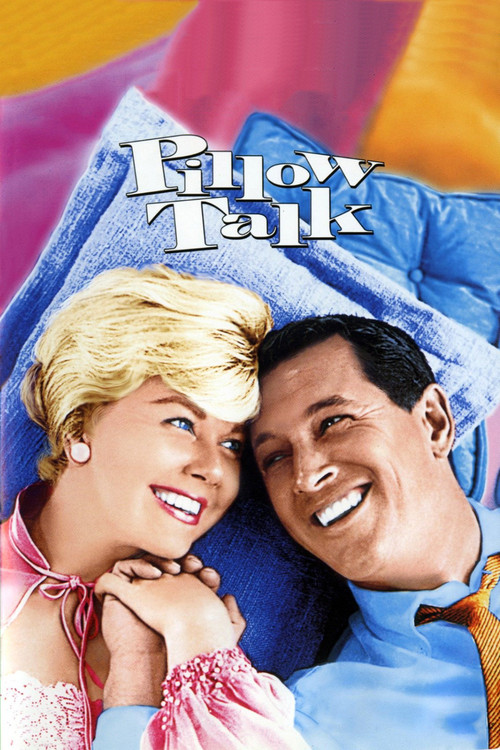

Day’s fresh blonde beauty made her a natural for films, and she was cast in her first picture, “Romance on the High Seas,” in 1948. She’d make a total of 40 movies over the next 20 years. Initially, she appeared mostly in musicals, but it was quickly evident she had more to offer. Soon she’d be scoring in dramas and comedies as well, including the film that brought her only Oscar nomination: “Pillow Talk” (1959), the first (and best) of her three wildly popular outings with Rock Hudson.

Day’s particular magic lay in bringing a sense of joy and optimism to her audience. Her naturally upbeat, resilient spirit was infectious. Her own words say it best: “I like joy; I want to be joyous; I want to have fun on the set; I want to wear beautiful clothes and look pretty. I want to smile and I want to make people laugh. And that's all I want. I like it. I like being happy. I want to make others happy.”

Later on, she would sorely need that resilience. In 1968, her third husband and manager, Martin Melcher, died suddenly of a heart attack. In the wake of his death, Doris discovered that Melcher’s business partner, Jerome Rosenthal, had squandered all her money. Just as her movie career was starting to wane, she found herself badly in debt. Melcher had also committed her to a television series and several network specials without her knowledge.

Doris soldiered on as she always had, and her series was a success, running five seasons. However, it would take nearly twenty years of litigation before Rosenthal was finally disbarred and Doris received a settlement.

By this time, she had moved to Carmel, California and taken up the cause of animal rights with a vengeance. She remained close to her only son, Terry Melcher, a former record producer, with whom she shared ownership of a nearby hotel. (The once wild-living Melcher had achieved notoriety via his indirect involvement in the Manson case. Terry had auditioned Charles Manson’s “band” at one point in the late sixties, and rejected them. Terry had then subleased his house to Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate for the summer of 1969. Having received a less-than-courteous welcome on his first unannounced visit, Manson decided to return, with horrific consequences).

Melcher would die of melanoma in 2004, but Doris lives on. Though the honors have piled up, she has shunned the spotlight, partly due to her fear of flying. About her advancing age, she had just this to say: “Oh, I have my little aches and pains now and then, like everyone. But I've truly been blessed with good health.”

We’ve been truly blessed as well — by Doris Day.

More: Why Rock Hudson Was So Much More Than a Symbol of AIDS