Dick Powell: always underrated, and today, perhaps even unknown. While any movie buff worth their salt will certainly remember him, for most anyone else not holding an AARP card, the mention of his name will likely elicit a blank stare. They may even mistake him for that dapper fellow in “The Thin Man.” (Note: he and William Powell were not related.)

In his hey-day, from the early thirties to the early sixties, he was a very big name indeed, and with good reason. Like few other figures in show business, Powell had an uncanny knack of reinventing himself: first, as a big band crooner, then a musical star, next a serious actor, then a director and finally, an enormously successful producer in the infant medium of television.

But there’s more to Dick Powell than his resume. He was, in my view, one of the most likable players on the big screen. He had a down-to-earth, easy charm that made him particularly relatable. I would see an indifferent Dick Powell film just to watch Dick Powell (particularly his later work), and for me that applies to very few performers.

Richard Ewing Powell was born in Arkansas in 1904, the second of three sons. His father was a businessman who traveled a lot, his mother an amateur musician. From any early age, young Richard and his brothers were encouraged to play instruments, and by the time his family settled in Little Rock in 1914, it was evident that young Richard had a beautiful singing voice.

After Little Rock College, Powell joined a series of bands as vocalist. He was based in Indianapolis, then Pittsburgh, where he drew praise as a highly entertaining master of ceremonies at several prominent theaters. By this time, he was also recording for the Vocalion label.

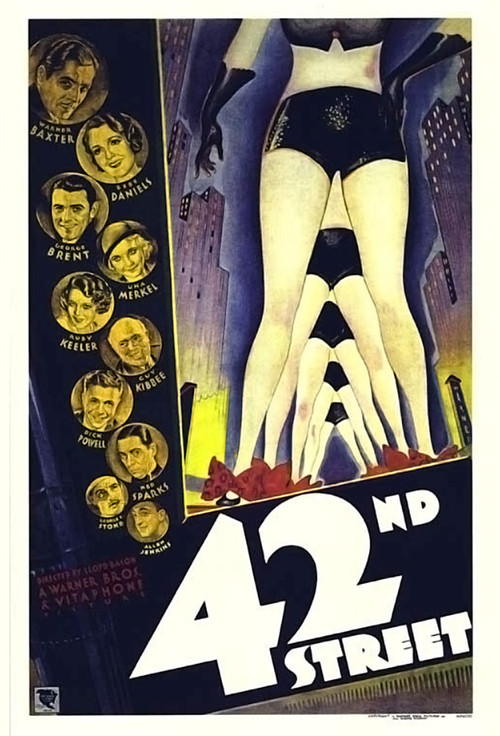

When Warner Brothers ended up buying that label, the young, magnetic singer was soon on their radar. They were sufficiently impressed to offer him a short-term contract in 1932. The following year, after appearing in four pictures, he was cast opposite newcomer Ruby Keeler in the immortal backstage musical, “42nd Street” (1933).

The wild success of this film rescued the movie musical from an early grave, and persuaded rival studio Radio Pictures to greenlight “Flying Down to Rio” (1933), the film that introduced the world to Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

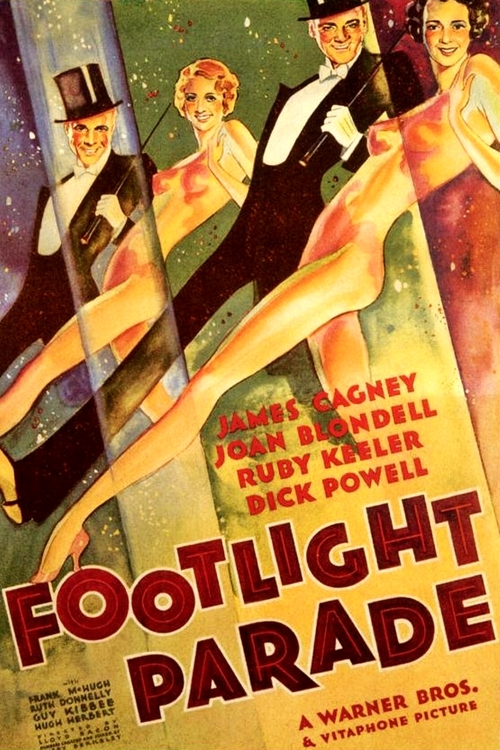

At the time, Warner Brothers did what most every studio has done ever since: milk a winning formula. Powell and Keeler would be paired in six more films over the following three years, including “Gold Diggers of 1933,” “Footlight Parade” (1933), and “Dames” (1934).

Both “42nd Street” and its successors were highlighted by the wildly inventive, elaborate dance numbers of Busby Berkeley, and lots of bouncy songs. Powell himself would introduce audiences to popular favorites like “Young and Healthy,” “Honeymoon Hotel,” and most memorably, “I Only Have Eyes for You.”

One of Powell’s co-stars on “Gold Diggers” and later Warner musicals was the blond comedienne Joan Blondell. The two clicked on set, and a romance blossomed. Though he was also seeing Marion Davies, William Randolph Hearst’s mistress at the time, he knew she would never leave Hearst, so he and Blondell finally married in 1936.

They’d have a daughter together, and he’d also adopt her son from a prior marriage. (Powell himself had previously wed model Mildred Maund years before but that union hadn’t lasted).

As the decade progressed, Powell was gratified by his success, personally and professionally, but at the same time, increasingly restless. He felt typecast by the studio, and also knew that the public was beginning to tire of the musicals that had launched him to fame.

He wanted to prove that he could do something different. As he put it at the time: “I'm not a kid anymore but I'm still playing boy scouts.” Finally, he decided to leave Warner Brothers for Paramount in 1940.

Though he had to appear in a few musicals at the outset, Paramount did cast him in some non-singing roles, including “Christmas in July” (1940), a solid if not outstanding Preston Sturges picture. As he approached forty, he realized he’d aged out of romantic leads.

Powell then heard about “Double Indemnity,” Billy’s Wilder’s upcoming thriller about an insurance man who plots with a client’s wife to bump off her husband and collect on his policy. He lobbied hard for the part of Walter Neff, but lost out to Fred MacMurray, an actor also known for good guy roles who was willing to play against type.

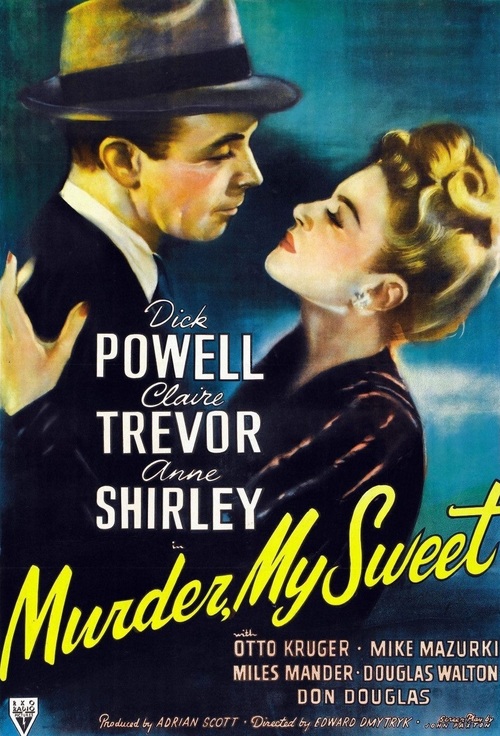

Then he got his chance. Edward Dmytryk was adapting “Farewell, My Lovely”, Raymond Chandler’s detective novel, to the screen and saw something unexpected in Powell. He’d have to be lent out to RKO, whose bosses were understandably skeptical about the director’s casting choice. But Dmytryk persisted and prevailed.

Dick Powell would become the first actor to play private eye Philip Marlowe on-screen. The film, released as “Murder, My Sweet,” was a hit and gave Powell’s film career the new direction he craved just as the new sub-genre of film noir was coming into its own.

Two years later, Humphrey Bogart would reprise the role in Howard Hawks’s “The Big Sleep.” Over the ensuing decades, Robert Mitchum, James Garner, and Elliott Gould would all take turns playing Marlowe.

At this point, Powell’s marriage to Joan Blondell was crumbling, as she fell for impresario Mike Todd and he for a younger actress named June Allyson. They divorced, and he and Allyson tied the knot in 1945. They would adopt one child, have one of their own, and also make a few films together.

Over the next few years, Powell starred in some solid, near-classic noirs including “Cornered” (1945, again with Dmytryk helming), “Pitfall” (1948), and “Cry Danger” (1951). His last great role came in Vincente Minnelli’s biting ensemble drama about the pitfalls of Hollywood, “The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952).

Now Powell wanted to branch out beyond acting. Television was exploding, with the networks hungry for programming. In 1952, he teamed with fellow stars David Niven, Charles Boyer, and Ida Lupino to form Four Star Television, which would produce shows and series. The company became wildly successful, largely under Powell’s leadership.

Dick also started to direct feature films around this time. With his trademark wit, he observed: “The best thing about switching from being an actor to a director is that you don't have to shave or hold your stomach in anymore.”

In 1956, he helmed “The Conqueror,” which was notorious for its offbeat casting of John Wayne as Genghis Khan. Later, the film became infamous for a more tragic reason: shot on location in Utah, the set was downwind from an above-ground nuclear testing site.

Over the coming decades, almost half of the cast and crew would get cancer, and nearly a quarter would die from it, including John Wayne and co-stars Susan Hayward, Pedro Armendariz and Agnes Moorehead.

Unfortunately, the director himself was also a casualty. Diagnosed with lung cancer six years later, Dick Powell succumbed to the disease the day after New Year’s, 1963. He was just 58. He left an estate valued at $10 million, a tribute to his business instincts and success as a producer.

But what I and his other living fans remember is up on the screen — it’s Dick Powell the actor. You liked him as the romantic crooner, young and carefree; or as the cynical tough guy, beaten down but always popping back up for one more round. You liked him either way.

Those who don’t know his work should. I think you’ll like him too.