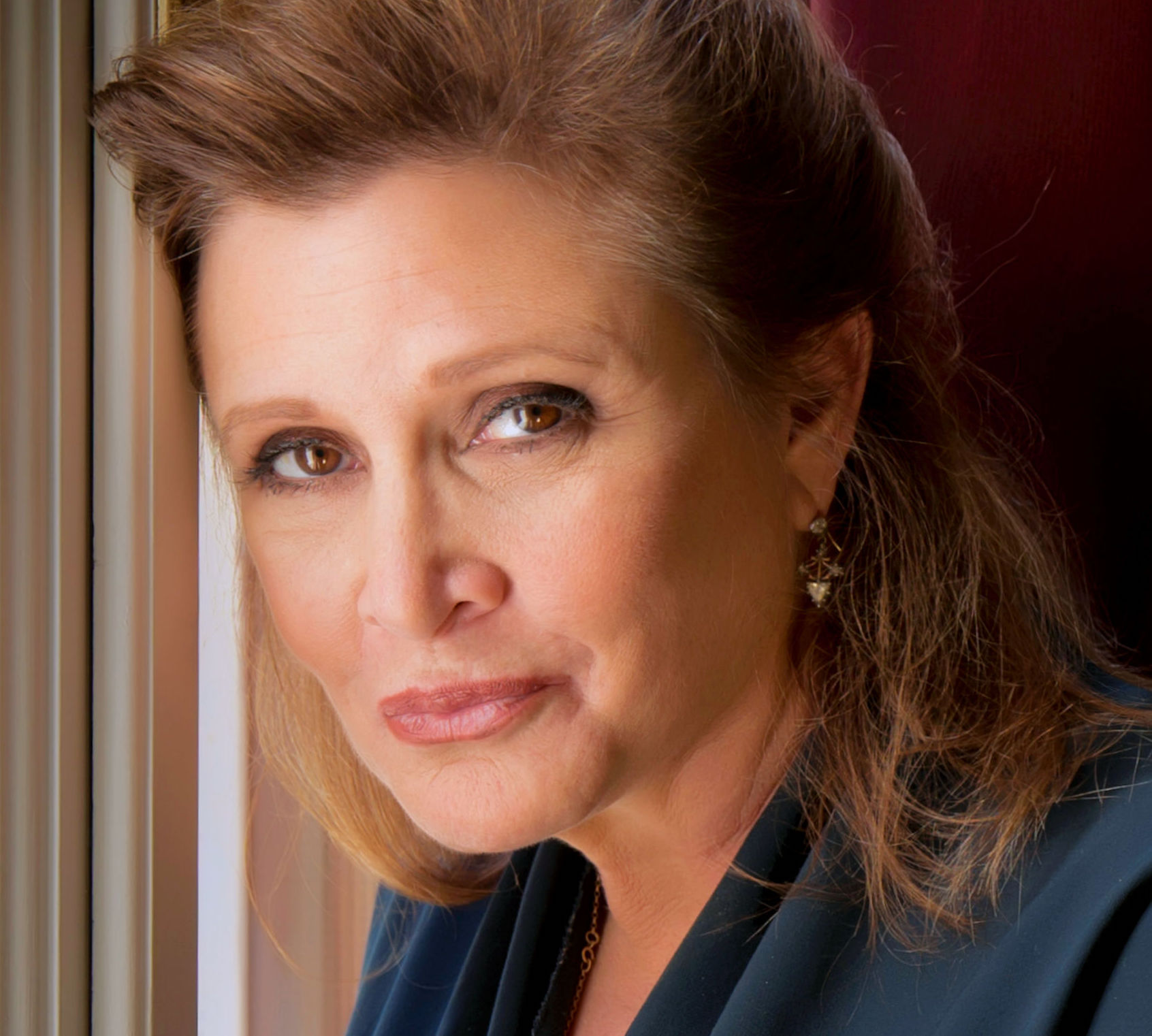

With a lot already written about Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds over the past week, I still wanted to chime in with my own thoughts on this stunning double loss.

Obviously it feels like there’s something mystical in this powerhouse mother-daughter combination leaving us just a day apart. As you dig deeper into their complex but painfully close relationship, it also seems strangely fitting.

First, it’s striking just how alike they were: both petite women with big personalities and talent who achieved overnight success in iconic movies at age 19; both immensely driven professionals who, in the face of personal misfortune, channeled their prodigious energies into their work.

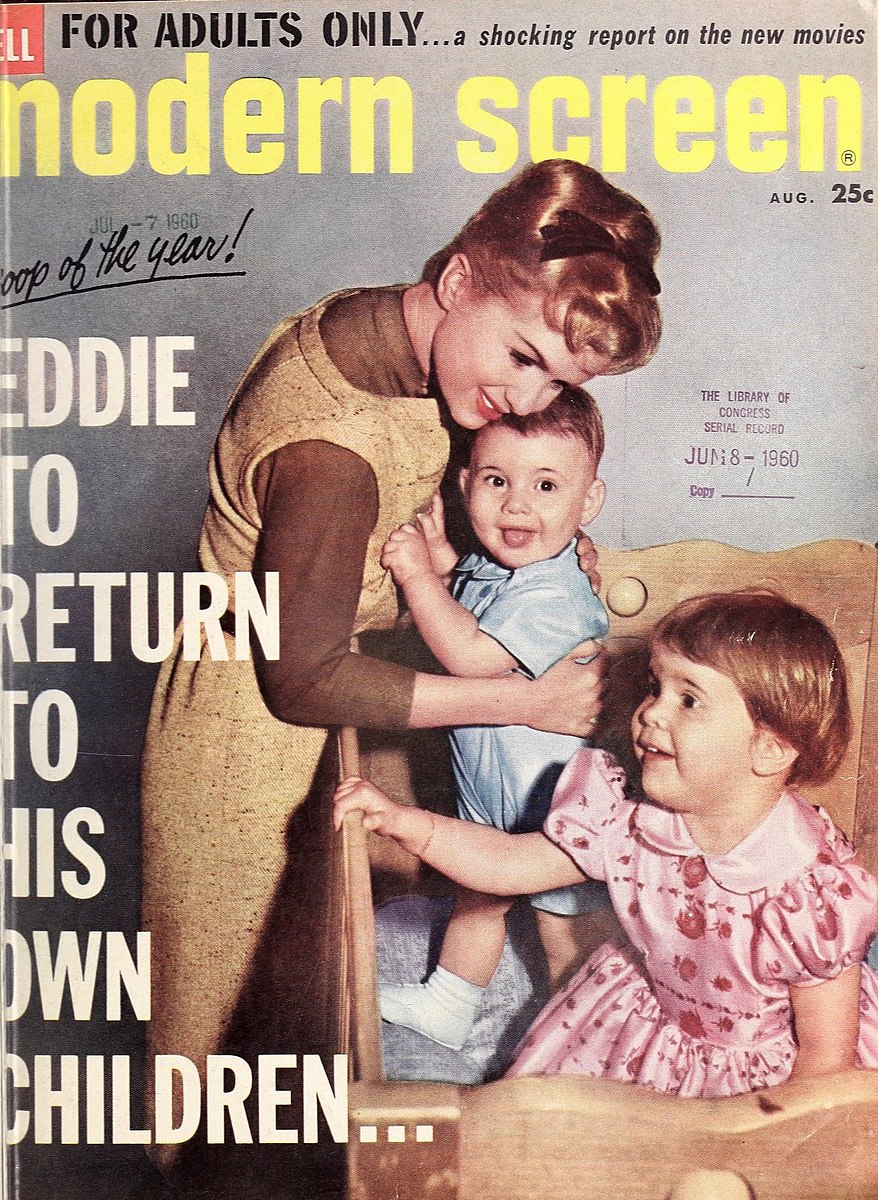

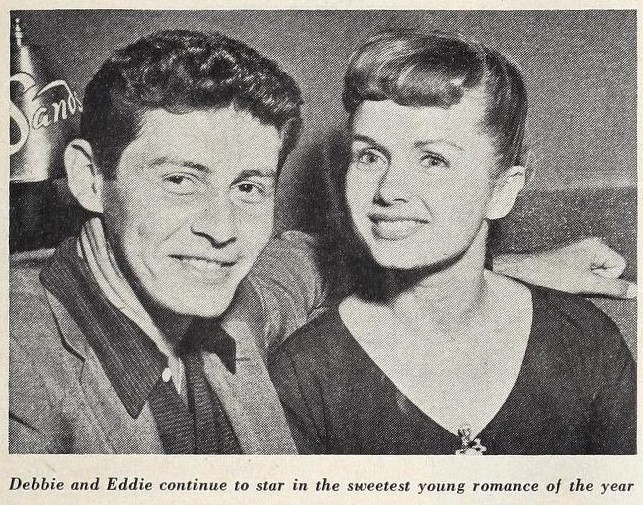

Both were badly hurt by the men in their lives: in 1959, Debbie had to endure a humiliating media circus when her first husband Eddie Fisher ran off with Elizabeth Taylor, the widow of his best friend, impresario Mike Todd. She was left alone with two infants. Later, her second husband would lose all her money. Carrie first experienced a broken-off engagement to Dan Aykroyd and a short-lived marriage to Paul Simon. Later, having settled down and had a child with agent Bryan Lourd (actress Billie Lourd), he’d leave her for a man.

Both were badly hurt by the men in their lives: in 1959, Debbie had to endure a humiliating media circus when her first husband Eddie Fisher ran off with Elizabeth Taylor, the widow of his best friend, impresario Mike Todd. She was left alone with two infants. Later, her second husband would lose all her money. Carrie first experienced a broken-off engagement to Dan Aykroyd and a short-lived marriage to Paul Simon. Later, having settled down and had a child with agent Bryan Lourd (actress Billie Lourd), he’d leave her for a man.

As it goes in many familial relationships, Debbie and Carrie loved each other deeply while driving each other crazy. With an absent father, Carrie looked solely to Debbie from day one, but as she hit adolescence and early adulthood, their conflicts escalated. Part of this was doubtless fueled by Carrie’s evident enthusiasm for drink and drugs.

Even in the face of a decade-long estrangement after Carrie’s first visit to rehab in the mid-eighties, the fierce, tight connection between them was never totally severed. The two would finally reconcile, and at the time of their deaths, they actually lived next door to each other.

Carrie knew early on that she wanted to follow in her Mom’s footsteps, but worried she could never match her beauty or talent. She was also ambivalent about the price of fame. In public, Debbie was always “on” to please her fan base, while Carrie receded into the background. Carrie resented having to share her, and disliked the glare and intrusion that came with celebrity.

Photo by Riccardo Ghilardi

One key difference between them: while Carrie was born into Hollywood royalty, Debbie grew up in straitened circumstances, a laborer’s daughter. Her family was close but rigidly devout and dirt poor. Show business had been Mary Frances Reynolds’s ticket to a better life. She’d never forget that, and held on tight to her career, always looking to the next movie, play, or nightclub gig.

This was not just out of desperation, but love. Debbie adored performing, plain and simple. And she loved the movies. Over the years she built up an incredible collection of Hollywood memorabilia, which she intended to display in a museum she’d launch in Las Vegas. This was one of several business ventures that didn’t work out.

Of the two, Carrie was the more sensitive and cerebral, often escaping into books as a child. Later, she’d become every bit as good a writer as an actress. While her mother was always stoic and upbeat about her personal difficulties, Carrie channeled her own daunting issues into her work.

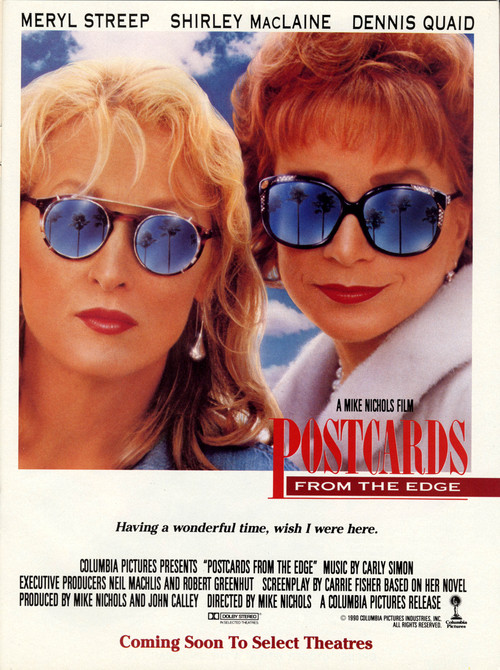

She’d portray her problems with drug abuse and her tense, conflicted relationship with her mother in her most famous book, “Postcards from the Edge,” which she’d then adapt into a movie starring Meryl Streep and Shirley MacLaine. This could not have been easy on her mother, but if she was resentful, she expressed it in private.

Carrie’s fearless, razor-sharp wit also led to “Wishful Drinking,” first a stage play and then a book, exploring her childhood, addictions, rehab stays, and diagnosis of bi-polar disorder. A sequel to “Postcards,” “The Best Awful There Is,” followed. Carrie also became one of Hollywood’s most sought-after script doctors, polishing dialogue for movies like “Hook” (1991), “The River Wild” (1994), “The Wedding Singer” (1998), and “Scream 3” (2000).

All the while, she knew she had a lot to live up to.

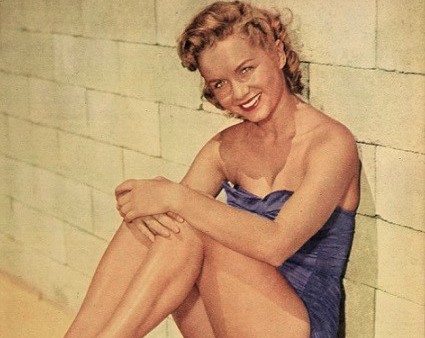

Whoever coined the word “trouper” was thinking of Debbie Reynolds. It all began when Mary Frances won the “Miss Burbank” beauty pageant in 1948, aged 16. It wasn’t just her looks that made the studio talent scouts in attendance take notice; she also did a mean imitation of Betty Hutton that wowed the crowd.

Warner’s quickly signed her to a contract, with Jack Warner himself changing her first name to “Debbie.” However, shortly thereafter the studio decided to dial down on musicals, so Debbie moved over to MGM, already known for their dazzling technicolor song-and-dance spectacles.

After impressing the brass with her portrayal of twenties-era singer Helen Kane in “Three Little Words” (1950), Debbie got her big chance in “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952). Co-directed by Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, Debbie would find herself in over her head fast. Fresh off the prior year’s “An American in Paris,” Kelly was one of the hottest commodities in the movie business. He had achieved that partly by being a stern taskmaster and perfectionist. The high standards he set for himself, he expected others to meet.

At that point Debbie could hoof it a little, but that was it. Now she really had to learn to dance, as a major movie was being shot! She’d later say that childbirth and making “Singin’ in the Rain” were the two hardest things she’d ever done.

Still there were bright spots. One day, Kelly brought her to tears before stalking off the set. Crying under a piano, Debbie heard a soft voice and looked up into the face of Fred Astaire, who had just happened by the set. He stood her up, dried her tears, took her through her steps, and when Kelly returned, she was ready

Buoyed by the success of this instant classic, Debbie embarked on a film career that peaked in the late sixties and included such titles as “The Tender Trap” (1955), “Tammy and the Bachelor” (1957, whose title song became a huge hit for her), “How the West Was Won” (1963), “The Unsinkable Molly Brown” (1964, her sole Oscar nod for Best Actress), “The Singing Nun” (1966), and “Divorce, American Style” (1967). She also voiced the title character in the animated “Charlotte’s Web” (1973).

In the early seventies, Debbie turned to the stage and television, professing to be turned off by all the nudity and profanity in the emerging school of moviemaking. The truth was that Hollywood was no longer making her type of picture.

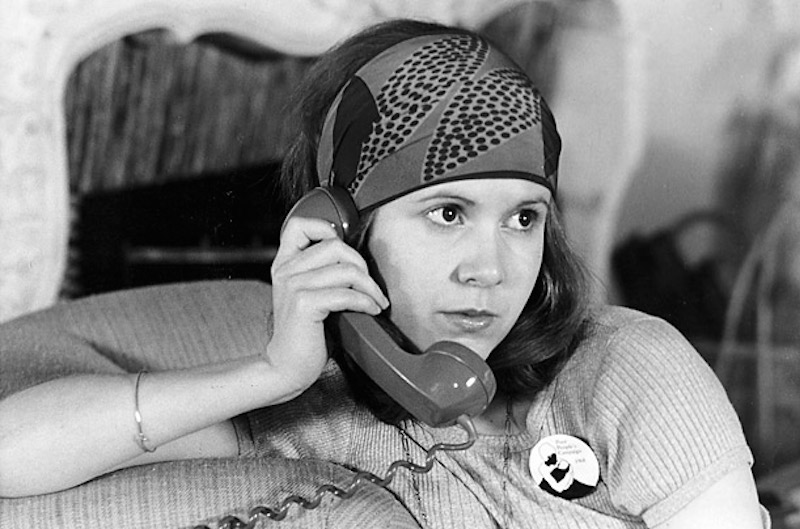

She had a successful TV show in 1969 that was abruptly canceled when she vehemently complained about the cigarette commercials the network was showing. She’d always regret making such a fuss. But she still had Broadway to conquer, and of course she did, starring in a popular revival of the twenties musical “Irene” (1973). This show was also Carrie’s first bow on Broadway; now just 17 and once again playing in her mother’s shadow, she found herself in the chorus.

Debbie would go on to appear in productions of “Annie Get Your Gun” and “Woman of the Year”. She also starred in her own Broadway revue. Then, years later, she’d make a welcome return to the big screen in two films of note: 1996’s “Mother,” with Albert Brooks, and the following year, “In & Out,” starring Kevin Kline.

Beyond her cherished Hollywood memorabilia museum, Debbie pursued other business ventures in the eighties and nineties, including a dance studio in North Hollywood and a hotel casino in Las Vegas. None of these clicked, but there was little time for regret.

By this point, of course, her daughter had come up in a big way. Two years after joining the chorus in “Irene,” Carrie made her film debut in Hal Ashby’s “Shampoo” (1975), starring Warren Beatty and Julie Christie. Though her part was small and reviews mixed, it was still a high-profile picture, and Carrie got noticed.

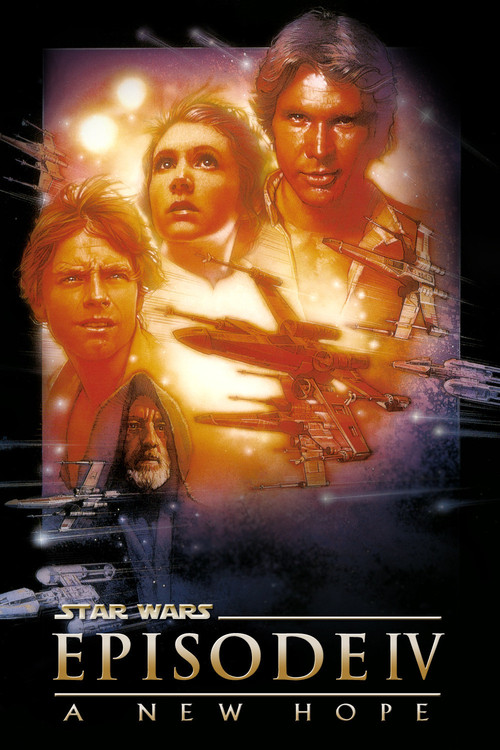

Just a year later, she beat out a slew of up-and-coming actresses like Meryl Streep, Glenn Close, Sigourney Weaver and Debra Winger to win the part of Princess Leia in George Lucas’s sci-fi feature, “Star Wars” (1977). No one involved, including the dour Lucas, had any clue that this movie would give birth to an enormous franchise.

The budget on that first film was so small that the actors were forced to fly coach. Debbie called George Lucas to complain loudly about this while Carrie was in the room. Finally, Carrie grabbed the receiver and said: “Mother, I want to fly coach, so please f**k off!”

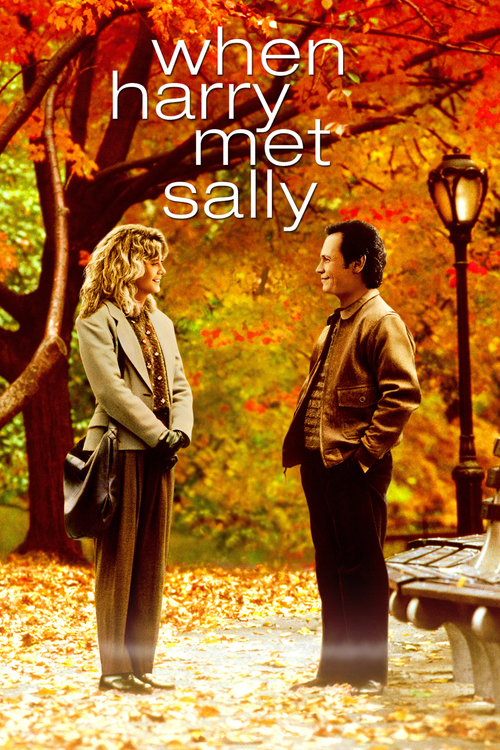

Carrie would be featured in the next two “Star Wars” sequels, 1980’s “The Empire Strikes Back,” and 1983’s “Return of the Jedi.” Decades later, she’d return for “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” (2015), and she also makes an appearance in an upcoming installment, which sadly turned out to be her final role. In-between, Carrie’s presence enhanced such memorable titles as “The Blues Brothers” (1980), “Hannah and Her Sisters” (1986), and “When Harry Met Sally” (1989).

Very soon, HBO will air their long-awaited documentary, “Bright Lights: Starring Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds.” Millions of their fans, myself included, will tune in to visit with Carrie and Debbie one last time, and bid these beloved performers a tearful farewell.

Like mother, like daughter... indeed.

Background photo by Greg Hernandez