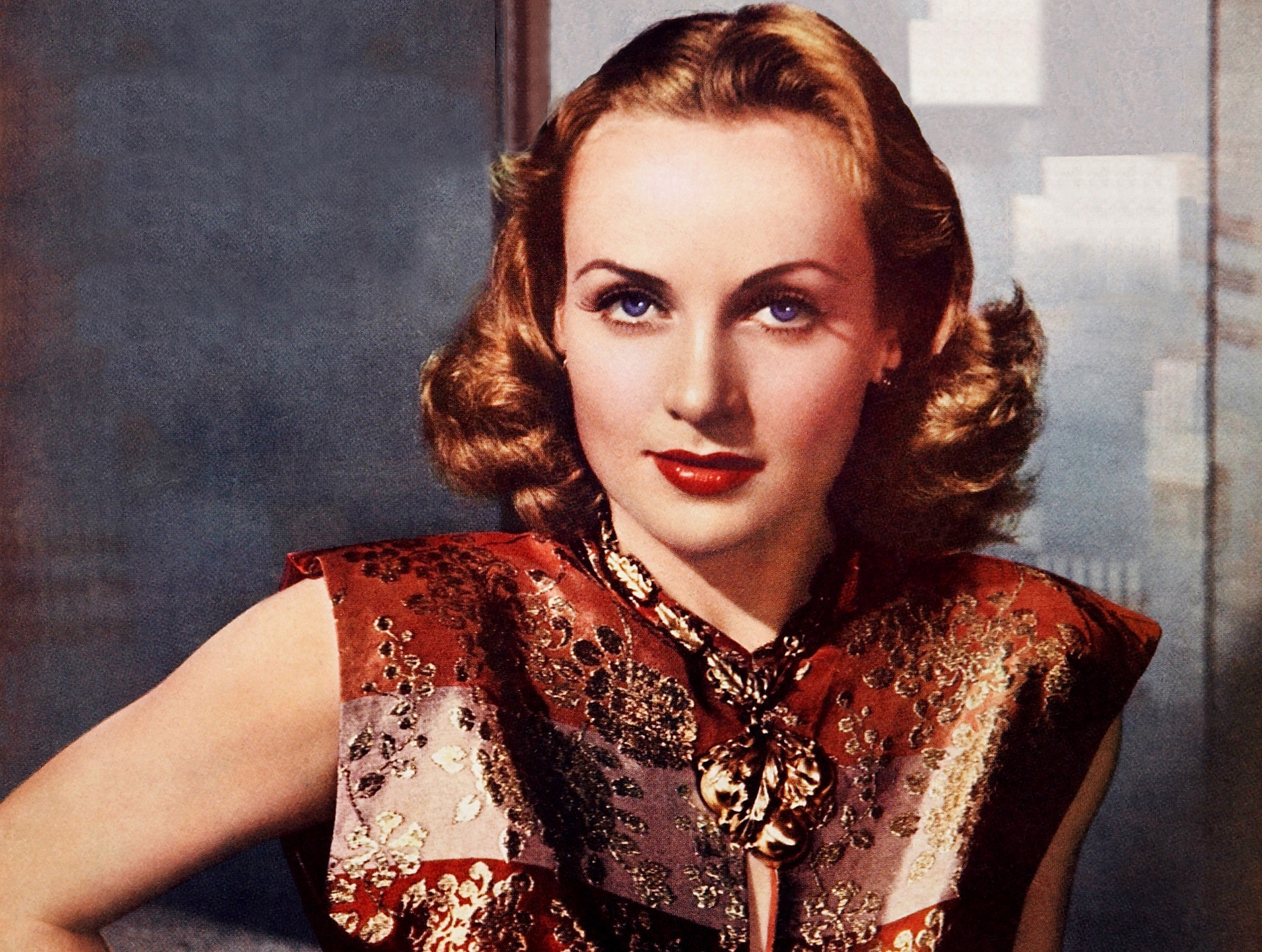

At age 33, Carole Lombard had it all. She was one of the highest paid actresses in Hollywood, and happily married to its biggest male star: Clark Gable. She had proven herself one of the industry’s top comediennes, but her beauty and talent could extend to serious roles too. Only good things lay ahead.

With our entry into the Second War, Carole was thinking way beyond her own success. She wanted to help her country win the war, and knew what her name could bring to that effort. So in January 1942, accompanied by her mother, Carole went back to her home state of Indiana to lead a war bond rally, which ended up raising an astonishing two million dollars.

The original plan was to travel back to Los Angeles by train, but Carole was impatient to return. Her mother supposedly had a premonition of tragedy, but Carole forced her to flip a coin.

Carole won, but the rest of the world lost, as the plane they boarded ended up crashing into the side of a mountain, killing all passengers instantly. It was just that quick and that cruel. All at once, husband Clark Gable was robbed of his wife, mother-in-law, and close friend Otto Winkler, the couple’s press agent. Those who knew him best say Gable never really got over the tragedy.

Carole had been born Jane Alice Peters in 1908 into an affluent family in Fort Wayne. When her parents divorced eight years later, Carole ended up living with her mother in Los Angeles.

Her natural beauty and buoyant spirit drew her to show business, and she made her first screen appearance at the age of 12. She came close to winning a part in Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush” at the tender age of 16, which gave her increased exposure. It was at this point that she changed her name to Carol (later Carole) Lombard, as it was felt that Jane Peters sounded too plain.

Carole won a contract with Fox at this time, and started learning the ropes of picture making. However, she was not happy with the quality of the roles she was asked to play. As she put it: “All I had to do was simper prettily at the hero and scream with terror when he battled with the villain.”

Two years later she seized the opportunity to work for the brilliant director Mack Sennett, becoming one of his famed “bathing beauties.” Under his tutelage, she developed the comedic chops that would propel her to stardom.

In 1930, Paramount came calling, and she signed with them. Over the next three years, Carole would make over twenty features there. One of them was 1932’s “No Man of Her Own,” starring up-and-comer Clark Gable. She later said there were no initial sparks between them. (One contributing factor may be that at this time, Carole was in the midst of a short-lived marriage to actor William Powell).

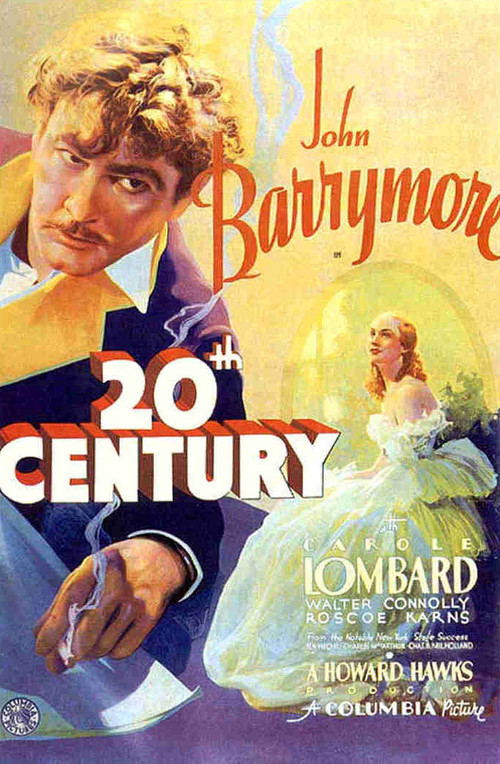

In 1934, her second cousin Howard Hawks approached her to star opposite John Barrymore in his upcoming screwball comedy “Twentieth Century,” about a broken-down Broadway producer who uses an extended train trip on the Twentieth Century Limited to convince the movie star he’d launched years before to help rescue his career.

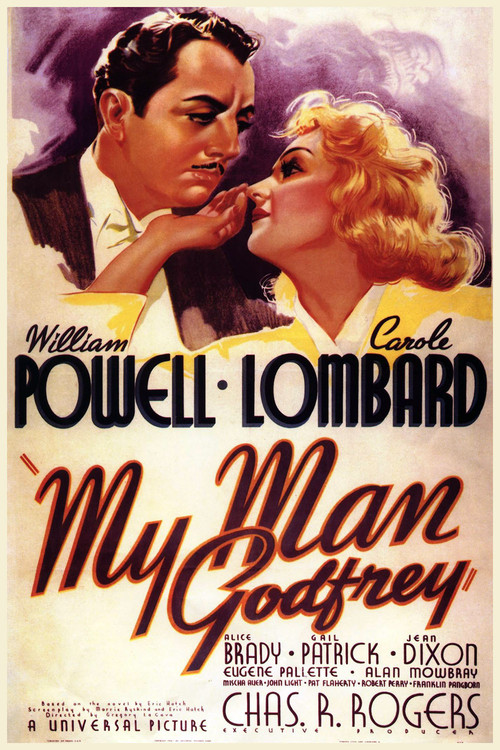

The film made Lombard a superstar. Henceforth she would be considered for most every starring role in the industry’s top comedies. Just two years later, she’d win an Oscar nomination playing opposite ex-husband Powell in the classic “My Man Godfrey” (1936).

In this, her signature role, Carole plays a flighty, dizzy heiress who falls for the family butler. On the strength of that performance, agent Myron Selznick negotiated for Carole the most lucrative contract of any actress in Hollywood. She would earn $450,000 a year, an astronomical sum at the time.

By this point, she was becoming seriously involved with Gable, whose wife Rhea Langham at first resisted granting him a divorce. However, Langham finally relented and the couple married in 1939. Together they bought a ranch in the San Fernando Valley, where they could indulge their shared love of the outdoors.

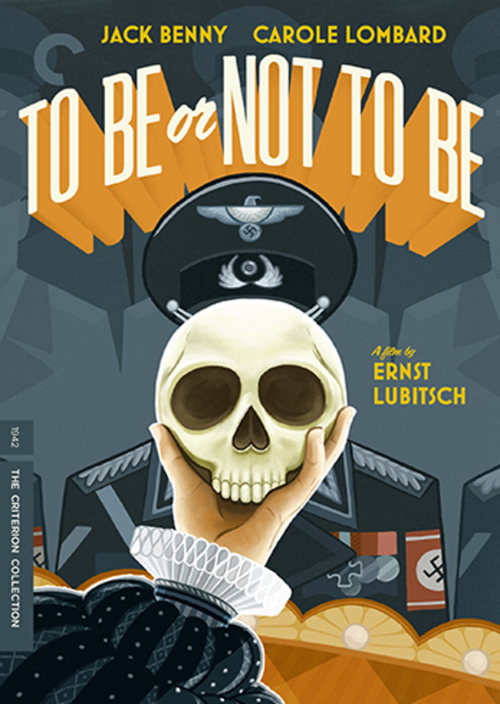

At her death, having ventured into dramatic parts, she’d returned to form in Ernst Lubitsch’s peerless wartime farce “To Be or Not to Be.” The film would premiere a month after her death. When her co-star Jack Benny heard about Lombard’s death, he was unable to do his radio show that evening. Instead, a selection of music was played.

Friends and fans not only admired Carole Lombard’s talent, they loved her personally. Nicknamed the “Hoosier Tornado,” by all accounts she was not only vibrant and fun but refreshingly plainspoken and down-to-earth in an industry built on playacting and illusion. She was more at home with the grips and technicians behind the camera than with the moguls in the front office. She preferred blue jeans to ball gowns. Fame never turned her head.

And, in the end, how she made us laugh. What still brings a pang of regret nearly eight decades later is thinking about the triumphs she might have had — and the laughs we might have shared — if she’d actually lost that coin toss on that fateful January day.