It all started with the hardboiled detective fiction which exploded onto the American popular culture way back in the roaring twenties. This new genre portrayed America’s evolving urban landscape as vividly as the Western genre did the rural frontier.

The originators of this type of fiction — notably James M. Cain, Dashiell Hammett, and Raymond Chandler — got their start writing serialized stories for the pulp magazines, then moved on to books and eventually, screenwriting.

And thus film noir came into full bloom.

Several conventions hold with this genre: 1) events usually revolve around, or culminate in, the commission of a serious crime (duh — but needs to be said); 2) the line between good and evil is blurred to the extent that the cops may be corrupt and the bad guys quite human (and likewise, the leading lady is rarely lily-white and virtuous. In fact, rather than supporting or deferring to “her man,” she may be actively working to undermine him (the witch!)); and 3) the prevailing mood is one of distrust and malevolence, as motives and allegiances remain murky until the end of the film, if not beyond.

For this purist, a true film noir should be in black and white; there’s not much “noir” without it, and B&W enhances the light contrast, the fog, and the shadows that help create the distinctive noir mood. Also, with rare exceptions like “Rififi” (1955), noirs should take place in America, since it began as a distinctively American form. (Even “Rififi” was directed by an American, Jules Dassin.)

In film noir’s hey-day, from the end of World War II through the mid-1950s, what an America it was. After nearly four years of bloody conflict, this country simultaneously confronted the reality of genocide in Europe, the advent of the Nuclear Age, and the Cold War.

Predictably, a more sober view of reality set in, characterized by a tendency towards wariness and paranoia. Yet since then, even as the national mood has brightened (or has it?), the best of these noir entries hold up, because treachery is part of human nature, and always fascinates.

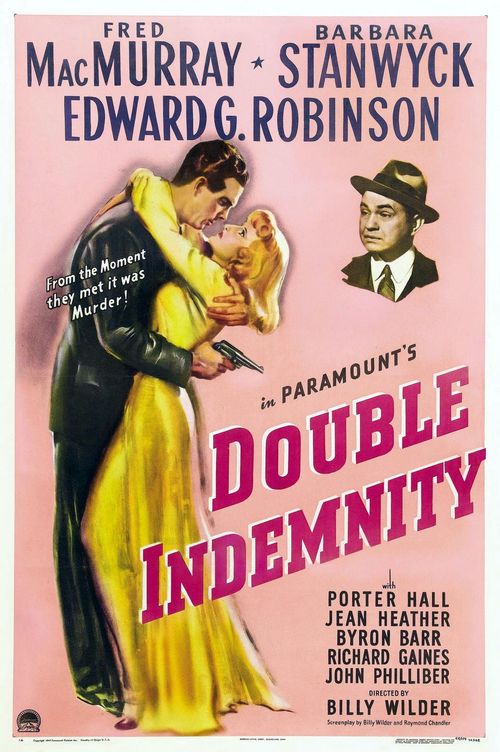

Many noir classics have entered the popular zeitgeist, from Billy Wilder’s “Double Indemnity” (1944), to John Huston’s indelible “The Asphalt Jungle” (1950).

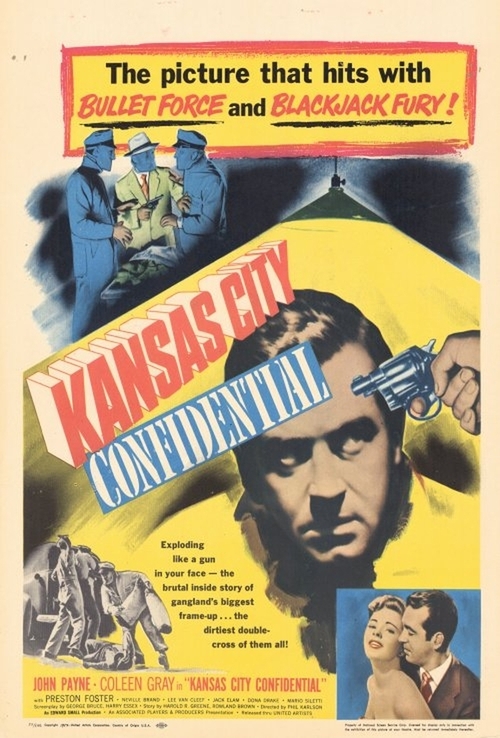

Yet lesser-known entries also abound that merit a look. Here are eight of my personal favorites.

Kiss Of Death (1947)

Crook Joe Bianco (Victor Mature) gets pinched for a heist, and after a tragic incident, turns informer against his gang. He makes parole and starts a new life. Then a killer with a cackling laugh (Richard Widmark) comes after him.

Out Of The Past (1947)

A private eye (Robert Mitchum) gets hired by slick gangster (Kirk Douglas) to retrieve his girl (Jane Greer) south of the border. Once located, she seduces the detective. Complications arise from there.

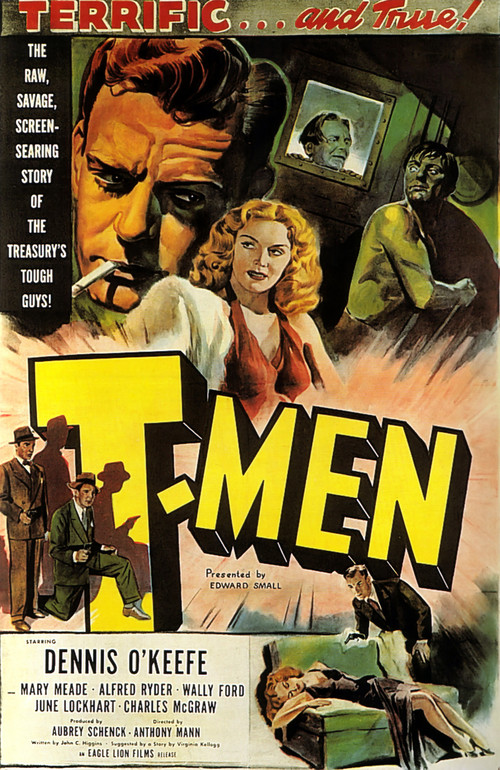

Raw Deal (1948)

A convict (Dennis O'Keefe) breaks out of prison with the help of a friend (Claire Trevor), and takes a hostage. Then he goes after the crime boss (Raymond Burr) who framed him.

D.O.A. (1950)

An accountant visiting San Francisco (Edmond O'Brien) unwittingly ingests a slow acting poison. With the little time he has left, he resolves to track down his killer, and find out why he was targeted.

The Narrow Margin (1952)

A police detective (Charles McGraw) escorts a cynical mobster’s wife (Marie Windsor) by train to testify against her estranged husband. Numerous hit men are on-board, but they don’t know what she looks like!

The Big Heat (1953)

A powerful mobster (Alexander Scourby) tries to rub out a cop (Glenn Ford), but mistakenly kills his wife instead. Now this detective is out for vengeance. Look for the inimitable Gloria Grahame, and Lee Marvin as a sadistic henchman.

Pick Up On South Street (1953)

A small-time pickpocket (Widmark again) picks the purse of a courier (Jean Peters) which contains some important microfilm everyone seems to want. Soon enough it feels like the whole world is after them! Character actress Thelma Ritter almost steals the show.

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Private eye Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) is investigating the murder of a blonde hitchhiker. He ends up tangling with a gangster (Paul Stewart) and a crooked scientist (Albert Dekker), and realizes the mystery goes deeper than one woman’s death.

Lots of films give us hope about the human condition, and obviously, we can always use a little more hope. Film noir, by contrast, is a guilty pleasure where we witness the denizens of society’s bottom rungs all stamping on each other’s feet for higher, safer position.

After seeing one of these movies, you may even feel slightly soiled. But you can always take a long, hot bath afterwards!