Katharine Hepburn remains the only actor or actress to be awarded four Oscars. Yes, Meryl has long since surpassed her on nominations, but Kate still leads on wins.

Few people now realize that by the end of 1938, after just six years in Hollywood, pundits were saying Kate was all washed up. In 1939, the year many point to as Hollywood’s finest, Kate didn’t have a single movie credit.

True, she got her first break early enough, as talking pictures in the early ‘30s were always searching for young, attractive Broadway-bred comers who could actually speak. Kate made an auspicious debut in 1932’s “A Bill Of Divorcement," opposite the aging, alcoholic John Barrymore (who played her father).

She was actually naïve enough to meet Barrymore in his dressing room for “line readings;" her upstanding Bryn Mawr sensibility was shaken on finding the aging actor eagerly awaiting her, reclined on his sofa, wearing only a beatific smile. The young ingenue shrieked and fled.

She survived that bizarre encounter, and went on to win her first Oscar the following year for “Morning Glory," about a young actress chasing after Broadway fame. She’d played the same part in real life only years before.

After that, her film output became uneven, as the studios struggled to figure out how to use her, and the public struggled to figure out what to make of her. To her detriment, she often seemed arch, mannish, and impossibly upper-crust. And yet, in the right roles, she could also exhibit a luminosity and depth of feeling few other actresses could match.

By 1938, film successes like “Little Women” (1933), “Alice Adams” (1935), and “Stage Door” (1937) were offset by clinkers like “Break Of Hearts” (1935), “Mary Of Scotland” (1936), and “Quality Street” (1937). Hard to believe now, but even the comedy classic “Bringing Up Baby” (1938) did not win raves on release.

When Kate was finally labeled “box-office poison” by the country’s exhibitors, she wisely decided to skip town for a while. So she went home, back to her family in Connecticut, and back to the Broadway stage where she’d had her first success.

Hepburn might have been on the outs in Hollywood, but she had a lot of friends and colleagues back East who still recognized her prodigious talent. One was the gifted Philip Barry, who’d been writing a play based on real life Philadelphia debutante Hope Montgomery Scott. He called Kate, and told her she was made for the lead. In fact, he’d written the whole thing with her in mind.

The name of the play (can you guess?) was “The Philadelphia Story,” and Kate loved it. So did the theatre-going public. Both she and the play were smash hits. Better still, Kate had negotiated the film rights, reportedly with a little help from her old friend and paramour, Howard Hughes.

Just then, with her much publicized Broadway success rekindling Tinseltown’s interest, Kate negotiated a stellar return engagement to do the movie version of the play with MGM. She’d get her favorite director, George Cukor, to helm the picture, and her favorite leading man, Cary Grant, to star, not to mention an up-and-comer named James Stewart to complete a triangle made in movie heaven. In a last stroke of genius, she would defer full salary for a percentage of box office receipts.

The movie, of course, was a triumph for her, personally, professionally, and financially. Kate was back, and Hollywood was eating crow (something it rarely did). If she left the film world again, it would be of her own choosing.

Kate’s very next film introduced her to the actor she most admired but had never met: Spencer Tracy. Once they’d both signed to do the fabulous “Woman Of The Year,” the film’s producer, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, introduced them on the MGM lot.

Kate was so nervous to meet the actor that when Tracy nodded his first greeting, she stammered, “You’re rather short, aren’t you?” The look of stone Tracy sent her caused Mankiewicz to utter the immortal reply, “Don’t worry, Kate. He’ll cut you down to size.”

With the success of “Woman Of The Year," Hepburn not only cemented her own comeback, but found a colleague, companion and soul-mate in Tracy who’d consume her attention and affection for twenty-five years.

With him she’d make eight more films, with at least half of them exceptional or close to it. Besides “Woman Of The Year,” there’s “State Of The Union” (1948), “Adam’s Rib” (1949), and “Desk Set”(1957). Of course, even the lesser Tracy-Hepburn outings were elevated by the duo’s potent on-screen chemistry.

And Kate’s work away from Tracy only seemed to improve with time. She was able to defy the conventional wisdom (and too often, reality) that actresses tend to get fewer good roles as they age.

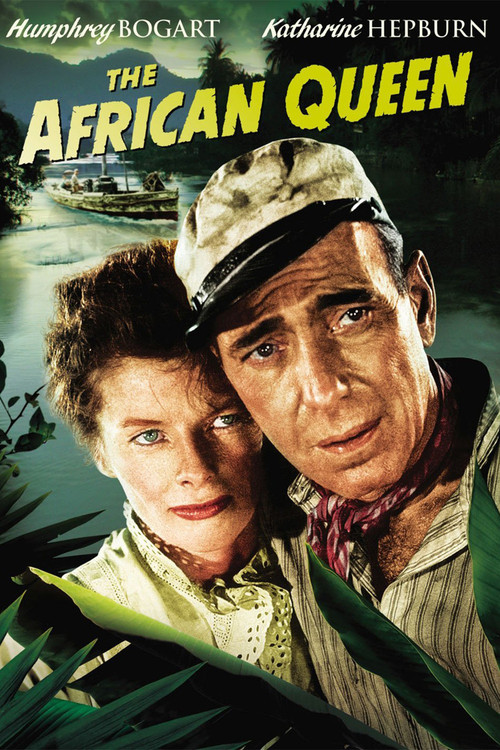

Witness titles like “The African Queen” (1951), "Summertime" (1955), and "Suddenly, Last Summer” (1959), and the astonishing fact that she won her last three Oscars after the age of 60 (for 1967’s “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner,” 1968’s “The Lion In Winter,” and 1982’s “On Golden Pond”).

Losing her beloved Spence shortly after “Dinner” wrapped in 1967 was devastating, but Kate poured herself into her work. Even in advancing age, she was never one to sit still. She continued doing TV and movie roles that suited her into her late eighties.

Katharine Hepburn died in 2003 at age 96. For all her many fans, she will always embody the can-do perseverance and sheer zest for living we saw on-screen. It was present away from the cameras too, and at no time more clearly than in that dismal winter of 1938.